Are You Brave Enough?

Are You Brave Enough?

“When Greg first met Butch Johnson, he was deeply impressed by Butch’s insight into the way organizations and leaders behave.

Butch taught him that the psychological limit of the leader inevitably becomes the psychological limit of the organization.

Very few top managers understand their own psychological limit, how it pervades the organization, and how they should change their profile.”

~ Ray Immelman, Great Boss, Dead Boss

For me, one word sums up this idea of “psychological limit” better than any other: Cojones (please don’t get hung up on the masculine connotation, women have cojones too).

In many of my clients over the years, I have observed that a key limitation (a.k.a. constraint) on their rightshifting journey has been their cojones, or more exactly their lack of thereof. This is what Ray Immelman is writing about in the above passage (the book explains the idea in greater depth). In a nutshell, he advises:

“Strong tribal leaders have capable mentors whose psychological limits exceed their own.”

There’s another word, not these days in widespread use, which also speaks to this issue: mettle.

met·tle/ˈmetl/

Noun:

1. A person’s ability to cope well with difficulties or to face a demanding situation in a spirited and resilient way.

2. Courage and fortitude: a man of mettle.

3. Character, disposition or temperament: a man of fine mettle.

The word has its root in the Greek, “metal”, with its connotation of mining, and digging deep, as well as the stuff of which we are made.

Organisational Mettle

From my perspective as an organisational therapist, I see organisations failing to step up and be all they can be, through a lack of organisational mettle. It’s often because things are too comfortable, too regular, with folks settled into a routine which seems to meet their personal and individual needs – at least, after a fashion.

I suspect it was…the old story of the implacable necessity of a man having honour within his own natural spirit. A man cannot live and temper his mettle without such honour. There is deep in him a sense of the heroic quest; and our modern way of life, with its emphasis on security, its distrust of the unknown and its elevation of abstract collective values has repressed the heroic impulse to a degree that may produce the most dangerous consequences.

~ Laurens Van der Post

Where does somebody’s mettle come from? Similar to my recent question regarding integrity – is mettle innate, or can it be learned, developed, expanded? And what is at the heart of organisational mettle?

“The true test of one’s mettle is how many times [or how long] you will try before you give up.”

~ Stephen Richards

Courage

For an insight into the source of mettle, we might consider the closely associated idea of courage. Courage comes – literally and metaphorically – from cœur (French) or heart.

“Courage is the most important of the virtues, because without courage you can’t practice any other virtue consistently. You can practice any virtue erratically, but nothing consistently without courage.”

~ Maya Angelou

Chinese and eastern traditions see courage as deriving from love. I find comfort in this.

What would you, your team, your organisation be capable of with limitless courage? Or even just a little more? How is your mettle related to the results you’re presently capable of achieving?

Judgement

I’m minded to caution – myself included – against the temptation to rush to judgement on individuals or organisations. Saying – or even thinking – “these folks need more courage” seems like it might be unhelpful from the perspective of therapy and e.g. nonviolent communication. Better to ask “how do you feel about the need for courage, the role of mettle, the psychological limits round here?”

Or, from an appreciative enquiry perspective:

“How much courage do folks here have already? How can we use it better? Do we need to build and develop it further, do we need more courage (in order to take us where we’d like to go)?”

Or, the Miracle Question from Solution Focused Brief Therapy:

“So, when you wake up tomorrow morning, what might be the small change, the thing you first notice, that will make you say to yourself, ‘Wow, something must have happened—we have broken through our psychological limits!’”?”

Or even, simply:

“What would you like to have happen? Is mettle necessary to that?”

I feel it’s a topic worthy of inquiry and discussion. And worthy of an open mind, too.

“The bitterest tears shed over graves are for words left unsaid and deeds left undone.”

~ Harriet Beecher Stowe

How about you? How do you feel about the need for courage, the role of mettle and the issue of psychological limits in organisational effectiveness? In your organisation? In your own life?

– Bob

Further Reading

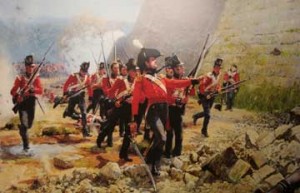

Forlorn Hope ~ Richard Scott’s blog post

Character Strengths and Virtues ~ Christopher Peterson, Martin Seligman

Great Boss, Dead Boss ~ Ray Immelman

Tribal Attributes ~ Ray Immelman (summary, pdf)

Hey there Bob,

I’ve said it before but good things can’t be repeated often enough. You have a fine pen and your writing does get one thinking.

Following up on your invitation to put forward thoughts on the matter in your article I find one important word missing – faith or belief. I think that great faith or belief in the endeavour one is set to accomplish in its self is what gives mettle (a new but fascinating word for me). I think not pushing through or achieving ones potential happens when leaders, and their advisers, start doubting if they are on the right track or have the knowledge and resources to accomplish what they set out to do. With an unwavering faith in a course or cause, individuals and groups of individuals, can achieve incredible feats. The energy that surrounds these types of people and groups tends to entice others to reinforce them by making sure they get the resources and leeway they need to succeed – it’s like buying into a dream, or in some cases not ending up on the losing side.

On the other hand too much faith or mettle can lead to disaster. Military and business history is full of examples where over confidence in ones capabilities combined with mettle have led to total disaster. I can recommend reading Norman Dixon’s “On the Psychology of Military Incompetence”. In his book he describes, with examples from military history, how leaders “cojones” not always are in the right place.

The point I’m trying to make is that blind mettle can be a recipe for disaster. Mettle is, do not misunderstand me, a good quality but it must be measured up against the reality of the situation. Good leaders will know which battles to avoid, which ones to wait out and which ones to fight.

Hi Petter,

Good to hear from you again. Thanks for joining this conversation.

Did you see my recent blog post “Faith”? I agree with your assessment of the role of faith (and purpose,too). I felt I didn’t want to repeat my self too much on that point. And yes I concur on the perils of overconfidence (hubris) as well. Aristotle in his Nicomachean Ethics described courage as the median between cowardice and recklessness.

And I’m fond of recalling the wise words of William Kingdon Clifford (The Ethics of Belief), too. I share his view that cojones must include an ethical dimension – in particular the ethics of seeking to know the true situation (and hence, what level of confidence is warranted).

– Bob

This post interested me because it felt like a very manly expression of this preoccupation with bravery or courage. From the use of “cojones” to many of the quotes about “mettle” which seem to consider mettle a manly attribute. I wonder whether a woman leader writing about organisational courage might write in a different way. (This isn’t a criticism of the piece, by the way, you can only write from where you are!).

My experiences of sharing my vulnerability, and in particular doing my learning in public, have (I am told) contributed to a growing courage in the colleagues – male and female – around me. Stephen Richard’s remarks about “mettle” speak to my own experience more clearly than some of the other remarks. Keeping on keeping on (often against dire odds) is definitely a form of courage. This can take the shape of grand battles, I know, but it is more often simply quiet tenacity.

Finally, I have noticed that when my organisation throws down the gauntlet of a new challenge, the perceived “strong” position is often to reject or refuse the challenge (it’ll never work, it’s a daft idea, it can’t be done). Asking for help is often seen as a “weak” position. However, I believe that accepting the challenge, and articulating clearly the support that will be needed to achieve that new objective is brave. It’s what I try to do.

I was thinking the same sort of thing. I’d be more inclined to the view that what is needed, at all levels of an organisation or business, is a love of the job; a passion for what you are doing; a clear view of where you are going; and the solid determination to get there; sprinkled with a generous helping of willingness to listen to advice and there lies the courage… The courage to admit you got something wrong or to dismiss unwanted advice and drive on through.

I believe that if you do not feel passionate about your business, if you don’t love what you are doing, then you cannot motivate those around you (or below or even above you).

Have you read Edwin Friedman’s “Failure of Nerve: Leadership in the Age of the Quick Fix”? Recommend it if you haven’t already. I know “leadership” is a dirty word for you but I think you’ll find his idea of being differentiated – knowing yourself and willing to be accountable for your own internal experiences – consistent with what you are saying here. Friedman says that the an organization cannot rise above the maturity level of its leaders. He further says that the one who maintains a non-anxious presence (has the cojones) in a difficult situation is the “leader” regardless of official standing in the group.

Unfortunately, Friedman died before the book was completed and some of his ideas are almost in point form

I think it is a function of the workplace culture to enable mettle. (And as mentioned in the post, this is often a reflection of the CEO’s own personality). There are some companies that repress mettle … and maybe they even do it inadvertently. Let’s say someone has intense passion about an innovative product. They develop the business case to get support to develop their idea. They incur the cost of company resources. And then they fail. In some companies, it would be all over for them. In order to have a brave culture that encourages passionate people to act on their ideas, they have to be allowed to have legitimate failures without repercussion. (And by legitimate I mean, for example, they don’t decide to drop the idea without warning.)

I’d also like to add that I believe some people are “wired” for bravery and some simply are not. But that’s OK because the true out-of-the-box thinkers (the brave folks who are willing to risk it all for their idea) need the less brave to keep them grounded and supported.

I particularly like the use of perspectives – I think this shows just how important it is to realise that each perspective offers a limited view of a problem / issue and how we need to recognise the need to see the whole and the parts.