Change, Kotter and Antimatter

[Tl;Dr: Let’s question the validity, applicability and utility of Kotter’s 8 Step Organisational Change Model – we can do better.]

I’ve assiduously read many books by Harvard Business School professor John P. Kotter – including his most prominent title, “Leading Change”. Back in the day, when I saw leadership as “the answer”, much of his writing made a lot of sense to me. The fact that it was “evidence-based” also added to its appeal.

“Kotter developed his change framework by observing transformation efforts in over a hundred businesses.”

~ Nitta et al.

The Kotter Model

For ease of reference, here’s one version of Kotter’s (1995) “Eight Steps to Transforming an Organization”:

- Establishing a sense of urgency

- Examining market and competitive realities

- Identifying and discussing crises, potential crises, or major opportunities

- Forming a powerful guiding coalition

- Assembling a group with enough power to lead the change effort

- Encouraging the group to work together as a team

- Creating a vision

- Creating a vision to help direct the change effort

- Developing strategies for achieving that vision

- Communicating the vision

- Using every vehicle possible to communicate the new vision and strategies

- Teaching new behaviors by the example of the guiding coalition

- Empowering others to act on the vision

- Getting rid of obstacles to change

- Changing systems or structures that seriously undermine the vision

- Encouraging risk taking and nontraditional ideas, activities, and actions

- Planning for and creating short-term wins

- Planning for visible performance improvements

- Creating those improvements

- Recognising and rewarding employees involved in the improvements

- Consolidating improvements and producing still more change

- Using increased credibility to change systems, structures, and policies that don’t fit the vision

- Hiring, promoting, and developing new employees who can implement the vision

- Reinvigorating the process with new projects, themes, and change agents

- institutionalising new approaches

- Articulating connections between the new behaviors and organizational success

- Developing the means to ensure leadership development and succession

As the ideas of Rightshifting and the Marshall Model have evolved, though, I’ve come to place less and less faith in this 8 Step Model, a.k.a. change framework. And with the emergence of the Antimatter Principle, that faith has just about evaporated entirely.

Personally, the evidence of the successful application of his model – what little I’ve found – seems to point more to successful organisational change being a function of people approaching the challenge deliberately, seeking and applying knowledge, rather than slavishly following a prescribed set of steps.

I accept that failed change initiatives can be dissected – to reveal some contributory omission of one or more steps recommended in the model, or poor implementation of same. I don’t see such post-hoc analyses as endowing the model with the gravitas – or even utility for folks considering change – that it seems to have acquired.

Change in Context

My own interest lies mainly in the transformations described in the Marshall Model. That is, fundamental change in the prevailing collective mindset of an entire organisation. More limited change – even though it may seem far-reaching, such as a “major” restructuring, change of business strategy, or change of market – within one mindset seems less interesting.

Such more limited change offers only limited uplift in organisational performance – with an upper bound of say 10 percent per annum improvement. (And yes, I note with regular chagrin Jerry Weinberg’s First Law of Consulting: “Never promise more than 10% improvement”).

These kinds of “limited” change seem hardly worth the effort, especially when we consider that simple continuous improvement (e.g. kaizen, evolution) can offer the same kind of gains, without all the angst and brouhaha implicit in “big-bang” organisational change initiatives. Better, surely, to punt for the 100 percent plus per annum performance gains offered by changing mindset – that is, if one is “going all-in”?

The Psychologies of Organisations

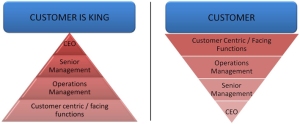

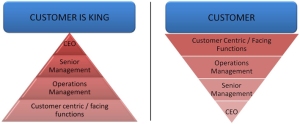

The most common criticism widely levelled at Kotter’s change model is its top-down nature. By which I mean, the change initiative is conceived at the top of the organisation, and then “pushed” down from the top into the middle and then lower tiers of the classic organisation pyramid (left-hand pyramid, below):

This approach may have some merit in “Analytic” minded organisations, where folks expect the higher-ups to dictate the structures, policies, etc., of the whole organisation. Although, even here, the nature of this “pushed” change, combined with the dysfunctional implications of “power-over” structures, hierarchy in general, and e.g. a prevailing Theory X orientation, means that any such top-down change is already on thin ice before it even starts.

But for the other kinds of mindset illustrated in the Marshall Model, Kotter’s model seem to lack relevance (cf Dreyfus, but for the organisation as a whole):

- Ad-hoc minded organisations are unlikely to accept any kind of structured approach to change.

- Synergistic organisations are unlikely to accept top-down change “pushed” onto people without consultation or meaningful participation.

- Chaordic organisations are unlikely to want to take the extended length of time to implement change that’s implied by Kotter’s model.

- And organisations “in transition” generally, are unlikely to realise what’s happening to them (absent familiarity with the Marshall Model) and attempt solutions unsuited to shifting their collective mindset (as the Kotter model has very limited applicability or utility in these situations, not least because it lacks any broad psychological or sociological underpinnings).

Attending To Folks’ Needs

Actually, there’s is a way to interpret the Kotter Model in harmony with the Antimatter Principle: If we establish the organisation itself as an equal stakeholder in things, and include its needs in the needs we’re all attending to, then we might begin to see how we can satisfy the various elements of Kotter’s Model:

- Establishing a sense of urgency

- If the organisation urgently needs to change, and folks understand that, everyone may be willing to attend to the issue.

- Forming a powerful guiding coalition

- By attending to everyone’s needs, we build the broadest-based and most powerful (motivated) coalition possible.

- Creating a vision

- The vision, of course, includes everyone’s needs. Everyone gets to participate.

- Communicating the vision

- Because everyone has been involved in step 3 (creating the vision), communicating it becomes much less of an issue.

- Empowering others to act on the vision

- No empowerment necessary – it’s built in, because it’s everyone’s vision.

- Planning for and creating short-term wins

- Whose needs come first? How do we spread the joy inherent in meeting folks’ needs?

- Consolidating improvements and producing still more change

- The Antimatter principle is self-reinforcing.

- institutionalising new approaches

- When the Antimatter Principle reaches a certain threshold, the organisation has “institutionalised” its new approach.

Wrap

I hope this post has gone some way to answering those many twitter requests I’ve had this week about my position on Kotter and his model. Would you be willing to provide feedback in the form of e.g. a comment, below, about the extent to which this post has met – or failed to meet – your needs?

– Bob