Octavian and the Seven Sisters (Working Notes)

Octavian Holdings has a problem. They are suffering as new technologies disrupt their existing product lines and change fundamentally what their markets demand – and what their employees want to do, too. What’s more, everyone in Octavian feels distinctly uneasy about the fact that their Iceberg Is Melting.

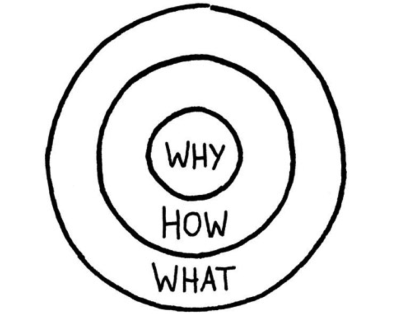

In an attempt to do something about it, Octavian has commissioned seven product development companies to write the software for a new line of products, products intended to meet the new demands of its key customers. It just so happens that each of the seven suppliers has a different one of the seven mindsets described in the Marshall Model.

[Why seven? So I can illustrate, through stories of how each one of the seven ‘sisters’ approaches the same basic brief, how each’s approach is a consequence of their respective collective mindset. 😉 ]

Please note: This post is simply some working notes describing the elements that I’ve chosen to illustrate through the narrative of each sister’s story. NB I mentioned this idea in my previous post. I’m minded to give each story its own separate post, but if you have any better ideas, I’d love to hear them. In fact, I’m publishing these notes not least so that folks can get an insight into my story-building approach, and interact with the evolving work whilst things are still malleable.

Here are the Seven Sisters

Prima – bio and key characters

Secunda – bio and key characters

Tertia – bio and key characters

Quarta – bio and key characters

Quinta – bio and key characters

Sexta – bio and key characters

Septima – bio and key characters

Prima’s Story (Ad-hoc, circa RI 0.4)

making it up as they go along

repeatedly solving the same or similar problems

unconscious incompetence

Theory X (unconsciously)

Autocracy (owner decides)

Random “management” styles (no real management tier)

Hands-on “management”, likelihood of micromanaging

Single loop learning

Lots of undiscussables, crucial conversations not had, folks oblivious to this

SDLC: Code&Fix

Massive WIP “Keep starting, not finishing”

Random (stochastic) flow

Lack of self-awareness

Ignorance of folks needs

Ignorance of covalence

Random feedback delay (up to a year, much feedback ignored or lost forever)

High cost of delay

Ultimately, delays lose Prima the contract

No project management

Little conscious respect for the individual

Much liking for heroism (overtime, firefighting, seat-of-pants)

Nothing measured (No operational measures)

Some joy and fun

Contemptuous of theory, principles, emphasis on practices and JFDI

Dismissive of tools

Absence of testing, no awareness of quality as an issue

Many defects seen by users and other stakeholders

Much waste (8 wastes) – unknown concepts though

Humane relationships rely on individual personalities

Everyone’s in it for themselves (Maslow)

Individual purpose

Blind to risks (and the very notion of the “risk�/reward” curve)

Nothing learned, except by a few so-disposed individuals

Learning seen as something that we did at school. No relevance to the real world.

Lots of design loopbacks (missteps, rework)

Chronic and acute failures in due date performance (conformance to schedules)

Use of third parties considered abhorrent (for some number of reasons)

Failure to invest in e.g. test environments

Chronic and acute deployment and post-deployment problems (discourages small deployments)

Everyone believes that success is a result of hard work and individual rock stars.

People work 9-5 , with some “special exceptions” for the “favourites”. If the company can afford an office, then folks (excepting the favourites) work in the office.

No explicit metaphor for “work”

Secunda’s Story (Novice Analytic, circa RI 0.7)

rigid adherence to rules

little or no discretionary judgement

potential to fall back to ad-hoc thinking

unconscious incompetence

Theory X (unconsciously)

Oligarchy (board decides)

Autocratic, command & control “management” styles (“mythic” management, rather than “scientific”)

Separation of “decison-making” from “work”

Some narrowly-skilled individuals (and many unskilled) with no real support system

Low levels of trust (cf lencioni pyramid)

Company policies actively (unwittingly) undermine trust (but there are as yet few of them)

Nascent project management – Gantt, Pert, MSProject, the whole useless nine years

Little respect for the individual

Much liking for heroism (overtime, firefighting, seat-of-pants)

Very few operational measures

Little joy

Dawning that maybe theory, principles have some value, still emphasis on practices and JFDI

Everyone’s in it for the money (extrinsic motivations)

Very local shared purpose (pairs, triples) working at odds with everyone else

Risk averse (no formal risk management, no appreciation of risk/reward)

Learning == training (and nothing else, from the org’s point of view)

Learning is in the domain of individuals – nothing much for the organisation to do other than some training

Lots of design loopbacks (missteps, rework)

Acute failures in due date performance (conformance to schedules)

Use of third parties considered only in extremis (for some number of reasons)

Investment in eg test environments is rare and exceptional

Chronic and acute deployment and post-deployment problems (discourages small deployments)

Most people believe that success is a result of imposed discipline, hard work and individual rock stars.

People work 9-5, in the office, with few “special exceptions”

Explicit metaphor for “work” as “office work” aka admin, non-creative

Tertia’s Story (Competent Analytic, circa RI 1.2)

situational perception still unwittingly focussed on local optima

all areas of the business are treated separately and given equal encouragement to improve

results across the organisation and through time vary widely in terms of quality and predictability

unconscious incompetence

Theory X (unconsciously)

Oligarchy (chain-of-command decides)

“Professional” command & control “management” styles (Taylorist, MBA style)

Separation of “decison-making” from “work”

Narrowly-skilled individuals with a limited support system

Low levels of trust (cf lencioni pyramid)

Company policies actively (unwittingly) undermine trust (and there are now many of them)

Very little respect for the individual

Some liking for heroism (overtime, long hours)

Almost no joy

Understanding that theory, principles have value, still emphasis on practices and JFDI (cog diss)

Everyone’s in it for the money etc

Local shared purpose – working at odds with every other silo/group

Risk averse (much formal risk management, little appreciation of risk/reward)

Lots of design loopbacks (missteps, rework)

Some acute failures in due date performance (conformance to schedules)

Use of third parties considered normal (but not well managed)

Investment in eg test environments is standard but costly

Chronic deployment and post-deployment problems

Most people believe that success is a result of imposed discipline, long hours, “process” and teamwork (teams of rock stars).

People work 9-5, in the office, with “special exceptions” being dictated by management according to company policy

Explicit metaphor for “work” as a factory (manufacturing, production line)

Quarta’s Story (Early Synergistic, circa RI 1.7)

coping with complexity (multiple concurrent stakeholders, needs)

action now partially seen as part of longer-term systemic goals

conscious, deliberate consideration of the organisation as asystem

potential for reversion to Analytical thinking

reduction in variability of results

conscious incompetence

Theory Y (unconsciously)

More consensus-style decision-making

Emergent self-organisation (i.e. not deliberate or systemic yet)

Some multi-skilled individuals with an early version of a operationalised support system

Good levels of trust (cf lencioni pyramid)

Joy

Emphasis on theory, principles having key value, still lingering affection for practices and JFDI

Almost everyone’s in it for the community (some liggers still)

Shared common purpose

Nervous of risks (formal risk management, appreciation of risk/reward)

Lots of design loopbacks (missteps, rework) – Agile reduces their impact but compounds their frequency

Good due date performance (conformance to schedules)

Use of third parties considered normal and desirable (for some number of reasons)

Investment in test environments is rarely necessary (and cost effective when it is needed)

Few deployment and post-deployment problems (movement towards small deployments)

Some confusion, argument and discussion about what accounts for “success”.

Most people want to believe that success is a result of intrinsic motivation, e.g. autonomy, mastery and shared common purpose.

People work flexibly, re: time, location, etc., with variable results and no common consensus on how to make it work effectively. At least the folks get to choose.

Explicit metaphor for “work” as a design studio (creative learning environment)

Quinta’s Story (Mature Synergistic, circa RI 3.0)

holistic view of situations, rather than fractured and faceted

awareness of constraints, system throughput and capabilities

appreciation for what is truly valuable (to customers, other stakeholders)

can distinguish between common and special causes of variation

streamlined decision-making, often evidence-base

uses maxims for guidance; meaning of maxims may vary according to context

results routinely fully acceptable

conscious competence

Theory Y (consciously)

Universal consensus-style decision-making

Intentional and systemic self-organisation (cf Sociocracy by design e.g. deliberate and systemic)

Multi-skilled individuals with an effective support system

High levels of trust (cf lencioni pyramid)

Much joy

Combining of theory, principles with experimentation, PDCA, practices

Everyone’s in it for the (learning) community (liggers choose to bail)

Shared common purpose – including continual improvement ethos

Loving risks (effective opportunity management, joy in appreciation and embracing of risk/reward)

Fewer design loopbacks (less missteps, rework). Adoption of SBCE

Excellent due date performance (conformance to schedules)

Both strategic and tactical use of third parties built into BAU (cf Keiretsu, Mittelstand)

Investment in test environments is rarely necessary (and cost effective when it is needed)

Almost no deployment and post-deployment problems (many, frequent small deployments)

Consensus yet ongoing discussion about what accounts for “success”.

Everybody believes that success is a result of intrinsic motivation, e.g. autonomy, mastery and shared common purpose., plus a laser focus on the core business fundamentals.

People work flexibly, re: time, location, etc., with consistent results and a common consensus on how to make it work effectively. Work per se is becoming irrelevant, replaced by e.g. “adding value” and “meeting needs”.

Explicit metaphor for “work” as a collection of fixed value streams

Sexta’s Story (Early Chaordic, Circa RI 3.5)

no longer reliant on rules, guidelines, maxims

intuitive grasp of situations, based on deep tacit understanding

driven by vision of what is possible

can integrate new idea, approaches, technologies with ease

conscious competence

Theory Y (consciously)

Systematic (sociocratic) decision-making

Intentional and systemic self-organisation and re-organisation

Multi-skilled individuals with an effective support system

High levels of trust (cf lencioni pyramid)

Much joy

Going beyond PDCA (scientific method) cf Feyerabend, Zen, Koen (Against Method)

A fresh (much wider/deeper) perspective on risks (effective opportunity management, joy in appreciation and embracing of risk/reward)

Some few design loopbacks (missteps, rework). Competence in SBCE, Trade-off curves, etc.

Due date performance (conformance to schedules), whilst excellent, is becoming irrelevant

Rapid delegation of work to to third parties built into BAU

Test environments continuously available

Few deployment and post-deployment problems (continuous deployments)

Consensus yet ongoing discussion about what accounts for “success”.

Most people want to believe that success is a result of positive opportunism – arbitraging fleeting market opportunities, and see intrinsic motivation, humane relationships, fellowship etc. as the only practical means to run an organisation that can do that effectively.

People spend as much time as they believe necessary to meet needs and add value. Hours, locations etc have become conscious means rather than ends.

Explicit metaphor for “work” as a collection of ephemeral value streams

Septima’s Story (Proficient Chaordic, circa RI 4.5)

knowledge of the evidence base and underlying knowledge in entirety

can teach chaordic mindset to new starters, partners in the extended supply chain

can use the knowledge interlinked with other knowledge

excellence achieved with relative ease

intuitively responds to unusual situations

results regularly delight and surprise

unconscious or reflective competence

Theory Y (consciously)

Optimised systematic (sociocratic) decision-making (optimised for speed)

High-speed, highly flexible self-organisation and re-organisation

Multi-skilled individuals with a comprehensive and highly responsive support system

High levels of trust (cf lencioni pyramid)

Much joy

Absence of management

Operationalisation of eg Deming, Ackoff, Senge, Lencioni, Feyerabend (Against Method), Zen, Koen etc.

Humane relationships are automatically strengthened and enhanced daily by many integrated behaviours and systems

Risk/reward at the heart of all decisions, all systems, all BAU

Almost no design loopbacks (missteps, rework). Competence in SBCE, Trade-off curves, etc.

Due date performance (conformance to schedules), whilst excellent, is almost entirely irrelevant

Rapid and highly cost- and quality- effective delegation of work to to third parties built into BAU

Test environments continuously available

Zero deployment and post-deployment problems (continuous deployments)

Consensus yet ongoing discussion about what accounts for “success”.

Everybody believes that success is a result of positive opportunism – arbitraging fleeting market opportunities, and sees intrinsic motivation, humane relationships, fellowship etc. as essential organisational capabilities.

People spend as much time as they believe necessary to meet needs and add value. Hours, locations etc have become unconscious, taken-for-granted – yet systemically part of work-as-usual – means rather than ends.

Explicit metaphor for “work” as a social phenomenon (community, organism, play, etc).

Common story template

Each of the seven stories follows this general form:

- The phone rings (or email, tweet arrives) at (company).

- A player reads, (discusses) and responds – illustrating the company’s general tenor in dealing with e.g. sales enquiries (ad-hoc, organised, etc).

- Some players discuss the brief.

- They close the deal with Octavian

- Work starts

- There’s some issues along the way

- Deliveries happen

- Octavian responds to the deliveries

- Wrap-up

– Bob