Why Improvement

Why Improvement

Some of my previous posts have discussed several aspects of organisational improvement and change, and in particular continuous improvement. I don’t think any of them really address the core reason I personally champion improvement as “a good thing”. Nor why I do my best work in a climate of intentional improvement of “the way the work works”.

For me, it’s about the people. I have often confessed in public to my motivation for putting so much effort into Rightshifting, the Marshall Model, and so on:

To reduce or end the egregious waste of human potential I see rampant in almost every knowledge-work organisation I visit.

Let’s set aside the rather thorny question of why I’m concerned about what’s happening to others. Instead, let’s focus on the drivers behind improvement, generally, in most organisations. And in this context, let’s also see if we can’t help explain why so few teams and individuals really care about – or seriously engage with – improvement.

Motivation to Improve

You might think that folks would be at least slightly interested in making their lives at work “better” in some way. Yet having seen so many workplaces where this is patently not so, I have to ask: “Why?” Why is it that folks do not generally seek to make things better?

I suspect at least part of the answer lies in the narratives organisations use to talk about improvement. These narratives almost always focus on outcomes such as improving profits, increasing returns to shareholders, or improving customer satisfaction. I have never heard a narrative that even mentions outcomes involving the opportunity for healthier and more fulfilling lives and relationships for the folks involved.

Can we really be surprised that folks are not very engaged with the idea of meeting the imagined needs of other, faceless groups of anonymous people, through some collection of notional “improvements”? Non-specific altruism is all very well, but it’s mayhap a bit dubious to base one’s entire improvement strategy on it? Especially when the core message so often is “we want you to work harder and longer, to make (other, rich) people even richer.”

It’s likely, as you read this, that your reaction falls into one of two camps.

Either “Yes – wouldn’t it be great if my organisation could see past the traditional “motivators, expectations and implicit employment contract, and understand that folks are capable of so much more – and stand to derive so much more – than is possible as things are.

Or, “Harrumph! We pay these people to do the things the company wants, and they damn well should put in their full effort”.

Which camp do you fall into?

Afterword

It’s become crystal clear to me over the years that the only effective way to build a so-called “continuous improvement culture” is to create the conditions under which folks might want to engage with the idea, and then afford them the free choice to so engage, or not. And if not engaging meets more of their needs than does engaging, don’t be surprised that they’ll do just that – not engage. Take it as a signal that you haven’t gone far enough (yet).

And then again, if the whole notion of building a culture of continuous improvement seems like too much trouble, or of dubious value, then folks may just intuit that you’re not so serious about seeing it happen.

And are those the best conditions pour encourager les autres?

– Bob

Further Reading

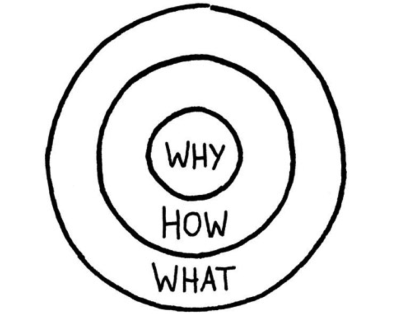

Start With Why ~ Simon Sinek

I seem to think like an engineer and when I see a problem, I want to change the system so it doesn’t happen any more.

When I was working at UCSF, I tried to get our internal voice mail system to work the way normal people actually used it, but the people who were directly in charge of that objected that I was interfering in their authority and the people who built the system claimed that they made it work that way because their customers required that. Both obstacles were sensible on their face but left us appearing to be stupid and irresponsible.

How can this be so?

When responding to a voice mail message, the system silently dropped the response on the floor unless it was ended with a ##. Why? Because early heavy users were traveling sales reps who hated unfinished responses terminated by losing the cell phone connection. But everybody else knows what to do when you’re done talking to a machine. Hang up.

Now that makes voice mail leavers believe that their message was ignored and the recipient was stupid or irresponsible. At the very least, voice mail recipients should be informed by a voice mail whenever a voice mail response has been dropped due to a missing ##. Best to ask before dropping. Second best, let the responder answer that indeed they wished that response to be sent. But instead my efforts got me in trouble and failed to get the problem fixed.

Reblogged this on Sutoprise Avenue, A SutoCom Source.