Are You Sitting Comfortably?

[TL;DR: How most folks stick to their comfort zones, and what that means for the businesses they work in.]

“No matter how comfortable we are, we always have to take the next step.”

~ Steve Jobs, re: the creation and naming of NeXT and NeXTStep

I like getting outside my comfort zone. Well, not like, exactly. It’s more that I feel compelled to do so, and quite often. I seem to have some voice inside my head saying “This is not good enough. Break out of your comfort zone – and push the envelope, again.” I guess I like the feeling that psychologists call “eustress“.

“Everyone needs a little bit of [positive] stress in their life in order to continue to be happy, motivated, challenged and productive. It is when this stress is no longer tolerable and/or manageable that distress comes in.”

A Mentor Can Help

In “Great Boss, Dead Boss” the author Ray Immelman expresses his view that a leader has to have the psychological courage to take each next step on the company’s journey. To have the urge to transcend their own emotional discomfort, and make leaps into the unknown, nevertheless. He also talks about the value of leaders having mentors with the psychological strength to help them grow even further.

Business Partnerships

In my working partnerships, over the years, I have often felt a sense of frustration with said partners and their reluctance to step outside their own comfort zones. We have lost opportunities, and compromised progress towards the (shared, common) purpose of the business because of the mismatch between our different levels of tolerance for discomfort.

Aside: By “opportunities”, I mean opportunities for personal growth, joy, success, enlightenment, fellowships, etc., and not so much just commercial opportunities.

And when talking with potential clients, etc., I regularly see the same kind of dynamic; folks who are “settling”, comfy in their warm, cozy and safe comfort zones. History tells me these are folks I cannot work with for long – or at all.

I’ve often found myself introspecting:

“What’s more important? Harmonious relationships, loyalty, friendship, etc. – or progress, taking the next step?”

Somehow, finding an acceptable balance over the longer term has eluded me. Maybe this, too, has something to do with needing to take the next step, make progress, move on.

Consequences

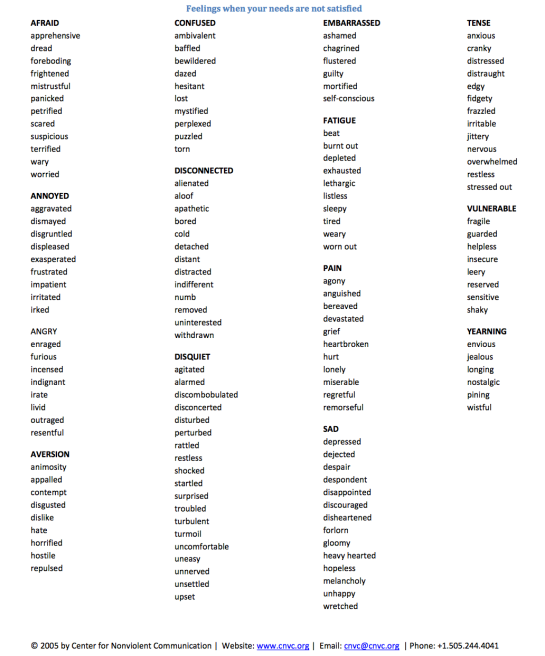

Working in e.g. an organisation, team or partnership where there’s a mismatch in folks’ tolerance levels for discomfort; where some folks want to take the next step and others are comfortable in their comfort zones, can lead to:

- Frustration.

- Distress.

- Demotivation – for the comfort-seeking and the discomfort-seeking folks, both.

- Distraction.

- Anxiety.

- Withdrawal.

- Maladaptive and depressive behaviours.

- Dysfunctional social interactions.

- Impaired cognitive function.

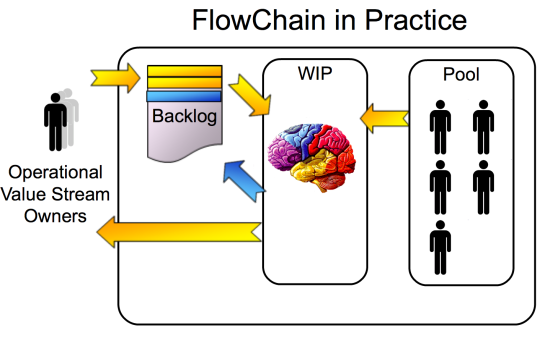

I see a tolerance for discomfort, an impulse to step outside one’s comfort zone, as closely correlated to organisational effectiveness (a.k.a. Rightshifting Index). And another reason to seek to match folks with similar tolerance levels.

Solutions?

I’m not sure even now, having experienced many instances of seeing folks stuck in their comfort zones, and the doldrums that result, that I have any answers or advice on how to deal with this, except perhaps Immelman’s:

“Strong tribal leaders have capable mentors whose psychological limits exceed their own.”

~ Ray Immelman

Oh, and talking about the topic. Maybe this post can serve your team or company as an entry point into that kind of discussion?

How about you? Are you inured to your comfort zone? Have you a story about some time when you stepped beyond that zone and found something wondrous?

– Bob

Further Reading

A Closer Look at Intrinsic Motivation ~ Kendra Cherry

The Science of Breaking Out of Your Comfort Zone ~ Alan Hendry