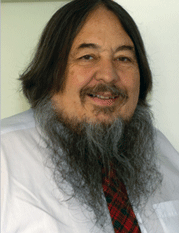

P Grant Rule: Pioneer in Software Development Processes

Peter Grant Rule was a British computer scientist who made important early contributions to the field of software development processes and methodologies. Though not as well known as some pioneers in computing, Rule’s innovative thinking influenced many modern software practices. He was also a dear friend of mine.

Career and Accomplishments

Grant had a long career working on cutting-edge software projects for aerospace and military applications in the 1960s-1980s, including work on several air defence systems. Some of his major accomplishments include:

- Developing one of the earliest fully automated software production systems, known as LRTS, whilst working on a radar command and control system in the 1960s.

- Pioneering automated requirements analysis techniques as part of the LRTS automated software process.

- Creating novel test automation, simulation and verification processes as part of end-to-end automated software development.

- Leading development of the innovative Janus Ada programming language, a predecessor to modern Ada.

- Managing the innovative SSADM structured analysis and design methodology project for the UK government in the 1980s.

- Making early contributions to software size measurement and metrics, including involvement in the development of function point counting.

- Authoring books and papers synthesising best practices in software requirements, design and project management.

Contributions to Software Processes

Grant was one of the first to emphasise automating analysis, design and testing as part of a comprehensive software production process. Whilst automated coding was not new, Grant broke ground in areas like automated requirements processing, simulation, and verification.

Grant’s methods like LRTS – and later, SlamIt, complementary to FlowChain – pioneered integrating these automated processes into a streamlined software lifecycle optimised for productivity and quality. Many of his technical innovations later became standard practice.

Grant also helped advance software measurement techniques like function point analysis that are now commonly used to measure software size and estimate effort.

In essence, Grant Rule was an important early thinker in structured software processes, automation, metrics and productivity – founding concepts that remain relevant today. Though not a household name, his innovative work helped pave the way for modern software practices.

Legacy and Impact

Although not as widely remembered as some other software pioneers, Peter Grant Rule’s innovative work on automated software processes helped establish many concepts that are now fundamental to modern software engineering.

Rule was one of the earliest thinkers to recognise the potential for automating key phases of software development like requirements, design, coding, and testing. The pioneering LRTS system he architected demonstrated the viability of automated end-to-end software production at a time when code was still written manually.

Rule’s technical breakthroughs in areas like automated requirements processing, simulation, verification, and metrics anticipated many modern software best practices. He understood early on the need for formalised, engineered processes in software creation.

Principles Rule pioneered, such as integrated automation, structured methodologies, formal requirements, and software measurement, became widely adopted by the software industry decades later. He saw the future direction and potential of software practices before most.

Whilst not necessarily a household name, Rule’s visionary work on automation helped progress software development from an ad hoc craft to an industrialised engineering discipline. The modular, automated techniques he championed are now cornerstones of modern software approaches.

Rule helped pave the way for today’s automated testing, requirements tools, DevOps pipelines, and model-driven engineering capabilities that are revolutionising how software is built. The seeds of these innovations can be found in Rule’s pioneering concepts from the 1960s onwards.