My Organisational Psychotherapy Toolkit

When in a day of meetings last week, at one point we each introducing ourselves in a round-robin fashion. I naturally explained my chosen and preferred role these days – that of Organisational Psychotherapist. Given the room was full of software folks, I expected a few blank faces. What I did not expect was the ripple of schoolboy sniggering that ensued. Never mind. I learned something.

In the next break I was gratified – and my faith somewhat restored – in that some folks came up to me and asked some incisive questions about the concept of organisational psychotherapy. One of these questions was about the means and techniques at the disposal of the Organisational Psychotherapist. I responded by explaining about Positive Psychology and in particular Solution Focus. If I had had more time, I might have worked my way down the following list of the “tools” in my organisational psychotherapy toolkit:

Solution focus (Steve de Shazer and Insoo Kim Berg)

Solution Focus, borne out of the InterActional View studies at the Mental Research Institute, focuses attention on what’s been going right, on what works, and on what we should be doing more of. Its emphasis on taking small steps and keeping things simple means organisations can get started with it straight away.

The key principles of Solution Focus include:

- Focus on solutions, not problems.

- People already have the resources they need to change.

- Change can happen in small steps.

- Work with what you see – in-depth and up-front analysis offers few if any advantages.

Solution Focus derives from the talking therapy named Solution Focused Brief Therapy (one of a range of Brief Therapies). There’s also a great book “The Solutions Focus: Making Coaching and Change Simple” by Mark McKergow & Paul Jackson.

Further Reading

From the Interactional View ~ Carol Wilder

Dialogue (William Isaacs)

In his excellent book, Dialogue and the Art of Thinking Together: A Pioneering Approach to Communicating in Business and in Life, William Isaacs explains his experiences and methods regarding “The Art of Thinking Together”. Influenced by David Bohm’s work on dialogue (apparently) and making similar observations to Nancy Klein.

P.E.R.M.A. (Martin Seligman)

Professor Martin Seligman is one of the most famous living psychologists, having served as president of the APA in 1996, and making a number of important contributions to the field, including the learned helplessness conception of depression. He is also a pioneer in the field of positive psychology. According to Prof. Seligman, the PERMA acronym reminds us of five important building blocks of well-being and happiness:

- Positive emotion

- Engagement

- Relationships

- Meaning (a.k.a. purpose)

- Achievement

Prof. Seligman also writes, in his book “Flourish” about PERMA and the Positive Business. His work with positive psychology provides a number of well-researched techniques for improving well-being, including:

- What Went Well Today (Three Blessings)

- Active and Constructive Responding

- The Gratitude Letter

- The Gratitude Visit

- Strengths and Virtues (VIA Survey of Character Strengths )

- The ABC of effective living

I believe many such positive psychology techniques, developed for the individual, have equal application in organisational therapy.

StrengthsFinder (Marcus Buckingham)

StrengthsFinder provides an assessment (online or via the book) of an individual’s key strengths. As an example, here’s mine from a few years back. The same principles (although not directly, the research) can be applied to an organisation. Just having people share knowledge about their strengths can help build understanding and strengthen relationships. This helps the process of organisational therapy.

Social Styles (Wilson Learning)

Social Styles provides a means for groups of people to relate to each other better, with actionable advice on how to modify one’s own natural communication styles to better suit others. Again, this can help build understanding and strengthen relationships. This helps the process of organisational therapy.

Clean Language (David Grove)

Clean Language is a personal therapy technique which focuses exclusively on the metaphors and vocabulary of the patient/client/questionee. The philosophy and principles underlying this are outlined in e.g. this paper.

“Many clients naturally describe their symptoms in metaphor, and we find that when the therapist simply enquires about these metaphors using their exact words, the patient’s perception of the issues begins to change.”

The “Full Syntax” of Clean language is very minimal, consisting of the following few “questions”:

- And [their words].

- And when [their words] …

- … what kind of [their words] is that [their words]?

- … is there anything else about [their words]?

- … that’s [their words] like what?

- … where is that [their words]?

- … whereabouts [their words]?

I myself generally start out with one more question:

- Would you like something to happen / what would you like to have happen?

Aside: Finding NLP somewhat suspect these days, I see no reason to associate the two, excepting perhaps for historical reasons.

I am currently experimenting with the use of Clean Language in group situations. For example, using group metaphors to help a group to change its perceptions. Here, group can mean team, department or, ideally, the organisation as a whole.

Family Therapy (Virginia Satir)

Virginia Satir (1983) described the family as:

“An interacting unit that strives to achieve balance in relationships through the use of repetitious, circular, and predictable communication patterns.”

This sounds to me much like an organisation (a.k.a. a business). Satir saw the spousal mates as the architects of the family and contended that the marital relationship is the axis around which all other family relationships are formed. I see parallels in this with the organisation – with the executives and managers (or Core Group) as the (tacit) architects of the organisational psyche, and their (tacit) power structures as the axes around which all other relationships are formed. Thus organisational homeostasis is directly influenced by the power relationships in the organisation. Hence I find much in e.g. Virginia Satir’s approach to Family Therapy which applies (in a modified form) to organisational therapy. There’s a useful review of the field here.

Bohm Dialogue (David Bohm)

Bohm Dialogue is a technique invented by the noted physicist, philosopher and neuropsychologist David Bohm. His aim was for Bohm Dialogue to overcome or at least ameliorate the isolation and fragmentation he observed in society. I find it useful in helping to ameliorate the isolation and fragmentation we can all observe in most of our organisations today. Note: His prerequisites of equal status and “free space” can be difficult to provide in some organisations.

Further Reading

On Dialogue ~ David Bohm

Bohm Dialogue – Resource page at David-Bohm.net

World Café

The World Café method is “a simple, effective, and flexible format for hosting large group dialogue”. The fragmentation of the organisational psyche (amongst and between all the folks in an organisation) can make “treating” the organisation, as a whole, somewhat, erm, problematic. Hence the value of techniques for large group dialogue.

Further Reading

The World Café: Shaping Our Futures Through Conversations That Matter ~ Juanita Brown & David Isaacs

Nonviolent communication (Rosenberg)

Marshall Rosenberg created Nonviolent Communication, to help people exchange the information necessary to resolve conflicts and differences peacefully. “Violent” communication can weaken relationships and increase divisions within organisations. Nonviolent communication can therefore help strengthen relationships and reduce divisions.

“NVC is based on the idea that all human beings have the capacity for compassion and only resort to violence or behavior that harms others when they don’t recognize more effective strategies for meeting needs.”

~ Wikipedia entry

Further Reading

Nonviolent Communication: A Language of Life ~ Marshall B. Rosenberg

Cognitive Biases

I find it helpful to share the knowledge of our human fallibilities (biases in judgement and decisions-making) with the folks in an organisation. Wikipedia has an extensive list of cognitive biases. Many folks are unaware of the many ways in which the human mind can systematically deviate from rationality or good judgement. And even with awareness, we can often still sucker ourselves into making poor judgements.

One key aspect of effective organisational therapy is the organisation getting to understand itself better. Knowledge of the mores of the human brain is but one aspect of this journey towards enlightenment.

Further Reading

Thinking, Fast and Slow ~ Daniel Kahneman

Predictably Irrational ~ Dan Ariely

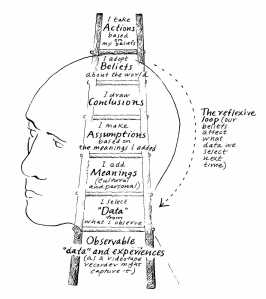

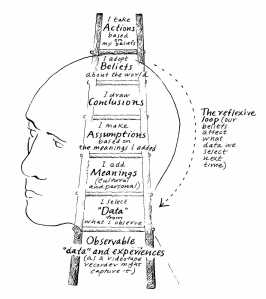

Action Science (Chris Argyris)

Chris Argyris‘s concept of Action Science begins with the study of how people design their actions in difficult situations. Although not strictly part of Action Science – which itself is more of a field than a tool – I use various “tools” from Argyris from time to time, including Ladder of Inference and Left-hand Column.

Cognitive Dissonance Theory (Leon Festinger)

Cognitive dissonance is the term used in modern psychology to describe the state of holding two or more conflicting cognitions (e.g., ideas, beliefs, values, emotional reactions) simultaneously. More specifically, the term refers to the sensation of unease or discomfort arising from such a state. Cognitive dissonance is one of the most influential and extensively studied theories in social psychology.

The idea of organisational cognitive dissonance is the collective-psyche analog of individual cognitive dissonance. I posit that an organisation can collectively suffer a sense of discomfort or unease when finding itself having to hold two or more conflicting cognitions simultaneously. One classic example of this is when an Analytic organisation finds itself host to an outbreak of alien, synergistic thinking during an Agile adoption or Digital Transformation.

Organisational cognitive dissonance theory warns that organisations have a bias to seek consonance among their cognitions. Much of what goes on in the organisation can be regarded as “dissonance reduction”.

Coaching for Performance (Sir John Whitmore)

In his popular book “Coaching For Performance“, Sir John Whitmore (a co-founder of the Inner Game Ltd.) argues for the use of effective questions to raise awareness and (self) responsibility. And, in the context of business coaching, for “a fundamental shift in management style and culture”. Some of the key tools I have used from this corpus, over at least the past 25 years, include:

- ARC (Awareness -> Responsibility -> Commitment)

- GROW (Goals -> Reality -> Options -> Will) Coaching Model (ex- Graham Alexander and Alan Fine)

- Team Development Model (with exercises)

Much of this has direct application to psychotherapy at the organisational level.

The Inner Game (Timothy Gallwey et al)

The “Inner Game”, developed by Tim Gallwey and friends, suggests that an individual makes accurate, non-judgmental observations of what they are doing, so that the person’s body will adjust and correct automatically to achieve best performance. A staple of e.g. sports coaching, I have adapted this basic principle to the organisational context. I posit that if an organisation uses accurate, non-judgmental observations of what it is actually doing, it will (to some extent) adjust and correct automatically to achieve best performance. This seems to me congruent with the “make it visible” vibe of e.g. personal kanban.

Further Reading

Effective Coaching: Lessons from the Coach’s Coach ~ Myles Downey

Theory of Constraints (Goldratt)

The Theory of Constraints is a philosophy developed by Dr. Eliyahu M. Goldratt, for application in organisations wishing to change for the better. Whilst not addressing issues of organisational health directly, Theory of Constraints provides a number of “Thinking tools” useful to the Organisational Therapist, including:

- Evaporating Cloud – a means to finding a resolution to conflicting points of view.

- Current Reality Tree – a focussing tool to help understand problematic situations

- Future Reality Tree – a means to explore the impact of proposed solutions

- Negative Branch Reservations – a complement to the Future Reality Tree

- Pre-requisite Tree – a means to plan the implementation of solutions

Note that much of the Theory of Constraints is congruent with various aspects of positive psychology.

Further Reading

The Goal: A Process of Ongoing Improvement ~ Eliyahu M. Goldratt

It’s Not Luck ~ Eliyahu M. Goldratt

Systems Thinking (Ackoff)

When dealing with whole organisations, and the collective organisational psyche, it makes little to no sense to work on parts of the organisation in isolation. Professor Russell L Ackoff created both Reference Projection and Interactive Planning as means to tackle whole-system change coherently.

Further Reading

Re-creating the Corporation: A design of organizations for the 21st century ~ Russell L Ackoff

Group Dynamics (William McDougall et al)

Group dynamics refers to a system of behaviours and psychological processes occurring within a social group (intra-group dynamics), or between social groups (inter-group dynamics). Group dynamics are at the core of understanding a range of social prejudices and discriminations. The history of group dynamics has a consistent, underlying premise: ‘the whole is greater than the sum of its parts.’ In organisational psychotherapy, this is a very congruent premise. The term was invented by Kurt Lewin (to describe the positive and negative forces within groups of people).

William McDougall was an influential early twentieth-century psychologist who wrote in his 1920 book, “The Group Mind“:

“We can only understand the life of individuals and the life of societies, if we consider them always in relation to one another. . . each man is an individual only in an incomplete sense.”

~ William McDougall, The Group Mind, 1920 (p.6)

Further Reading

An Introduction to Social Psychology ~ William McDougall

The Group Mind ~ William McDougall

Systems Archetypes (Senge)

System Archetypes, as describe by Peter Senge in his seminal book “The Fifth Discipline“, help people understand the interconnections and interrelations between e.g. the various parts of their organisation. We might compare this to the way in which neuroscience helps us understand the interconnections and interrelations between e.g. the various parts of our brains. Such an understanding can help elaborate the context for organisational psychotherapy.

The Fifth Discipline Fieldbook has many useful exercises and techniques for the organisational therapist, particularly in workshop settings.

Further Reading

The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Org. ~ Peter M. Senge

The Fifth Discipline Fieldbook ~ Senge, Kleiner, Roberts, Ross & Smith

Lateral Thinking (Edward de Bono)

Edward de Bono‘s key idea in his work on lateral thinking is that effective creative thinking requires us to take conscious steps to transcend our natural, logical, linear and critical mode of thinking in favour of a mode which recognises how the brain works. Some of the tools he has created for this include:

- Six Thinking Hats

- Po (Provocative Operation)

- Straatals

- Septoes

- DeBono Code Book

Further Reading

The Mechanism of Mind ~ Edward de Bono

I Am Right, You Are Wrong~ Edward de Bono

Discussion of the Method: Conducting the Engineer’s Approach to Problem Solving ~ Billy V. Coen

Managing Transitions (William Bridges, Kurt Lewin passim)

Managing Transitions is a book by William Bridges. In the book, he explore the psychology of change and presents an approach not unlike Kurt Lewin’s Unfreeze-Change-Freeze change model. The ideas in the book sit very comfortably with The Marshall Model’s idea of “Transition Zones”.

“The main strength of the [Bridges] model is that it focuses on transition, not change. The difference between these is subtle but important. Change is something that happens to people, even if they don’t agree with it. Transition, on the other hand, is internal: it’s what happens in people’s minds as they go through change. Change can happen very quickly, while transition usually occurs more slowly.”

Further Reading

The Bridges Transition Model: A Summary (pdf)

The Bridges Transition Model – MindTools.com

Client-Centered Therapy (Carl Rogers)

Carl Rogers was amongst the founders of the humanistic approach to personal therapy, and known for the concept of unconditional positive regard – accepting a person without negative judgment of their basic worth. In this, his work has many similarities with that of his student, Marshall Rosenberg (Nonviolent Communication). I choose to apply much of Rogers’ approach in the context of Organisational Therapy. That is to say, practicing an unconditional positive regard for the organisation as a whole.

Rogers did much research into what makes therapy effective, and found just three necessary “Characteristics of a Helping Relationship”:

- An unconditional, warm, positive regard for the client

- Genuineness and “congruence” on the part of the therapist

- Empathy and empathic understanding

Rogers expressed his Theory of Personality by way of Nineteen Propositions. Here are those Nineteen Propositions, but re-cast for the organisation:

- All organisations (systems) exist in a continually changing world of experience (phenomenal field) of which they are the center.

- The organisation reacts to the field as it is experienced and perceived. This perceptual field is “reality” for the organisation.

- The organisation reacts as an organised whole to this phenomenal field.

- A portion of the total perceptual field gradually becomes differentiated as the (organisational) “self”.

- As a result of interaction with the environment, and particularly as a result of evaluational interaction within its “self”, the structure of the (organisational) self is formed – a coherent, fluid but consistent conceptual pattern of perceptions of characteristics and relationships of the “we” or the “us”, together with values attached to these concepts.

- The organisation has one basic tendency and striving – to actualize, maintain and enhance the experiencing organisation.

- The best vantage point for understanding behavior is from the internal frame of reference of the organisation-as-a-whole.

- Behavior is basically the goal-directed attempt of the organisation-as-a-whole to satisfy its needs as experienced, in the field as perceived.

- Emotion accompanies, and in general facilitates, such goal directed behavior, the kind of emotion being related to the perceived significance of the behavior for the maintenance and enhancement of the organisation (organisational homeostasis).

- The values attached to experiences, and the values that are a part of the self-structure, in some instances, are values experienced directly by the organisation, and in some instances are values introjected or taken over from others (other organisations or sub-units or individuals within the organisation), but perceived in distorted fashion, as if they had been experienced directly.

- As experiences occur in the life of the organisation, they are either, a) symbolized, perceived and organized into some relation to the (organisational) self, b) ignored because there is no perceived relationship to the self structure, c) denied symbolization or given distorted symbolization because the experience is inconsistent with the structure of the (organisational) self.

- Most of the ways of behaving that are adopted by the organisation are those that are consistent with the concept of (organisational) self.

- In some instances, behavior may be brought about by organic experiences and needs which have not been symbolized. Such behavior may be inconsistent with the structure of the (organisational) self but in such instances the behavior is not “owned” by the organisation.

- Psychological adjustment exists when the concept of the (organisational) self is such that all the sensory and visceral experiences of the organism are, or may be, assimilated on a symbolic level into a consistent relationship with the concept of (organisational) self.

- Psychological maladjustment (dysfunction) exists when the organisation denies awareness of significant sensory and visceral experiences, which consequently are not symbolized and organized into the gestalt of the (organisational) self-structure. When this situation exists, there is a basic or potential psychological tension (a.k.a. organisational cognitive dissonance).

- Any experience which is inconsistent with the coherence of the structure of the (organisational) self may be perceived as a threat, and the more of these perceptions there are, the more rigidly the (organisational) self-structure is organized to maintain itself.

- Under certain conditions, involving primarily complete absence of threat to the (organisational) self-structure, experiences which are inconsistent with it may be perceived and examined, and the structure of (organisational) self revised to assimilate and include such experiences.

- When the organisation perceives and accepts into one consistent and integrated system all its sensory and visceral experiences, then it is necessarily more understanding of itself and its constituents (sub-units, individuals) and is more accepting of itself and its constituents and their respective, several needs.

- As the organisation perceives and accepts into its (organisational) self-structure more of its organic experiences, it finds that it is replacing its present value system – based extensively on introjections which have been distortedly symbolized – with a continuing organismic valuing process.

Rogers believed that every person can achieve their goals, wishes and desires in life. When, or rather if they do so, self-actualisation takes place. I believe this applies to organisations too. Although rarely. Sigh.

Further Reading

Six Amazing Things Carl Rogers Gave Us~ Dr Stephanie Sarkis

Carl Rogers ~ Saul McLeod

On Becoming a Person: A Therapist’s View of Psychotherapy ~ Carl Rogers

Client-Centred Therapy ~ Carl Rogers

Growth-promoting Relationships ~ Jon Russell

Ram Dass

Ram Dass is the author of the “counterculture bible” Be Here Now, and “one of America’s most beloved spiritual figures”.

“It is important to expect nothing, to take every experience, including the negative ones, as merely steps on the path, and to proceed.”

~ Ram Dass

Integrative Therapy (Jeffrey Kottler)

Jeffrey Kottler reminds us that therapists are people too. In his work with Integrative Psychotherapy, he focuses on both integration (fusion) of different therapies, and on integrating the personality – making it cohesive and bringing together the “affective, cognitive, behavioral, and physiological systems within a person”.

I have embraced and adapted this approach to the organisation, believing that much of the dysfunction, stress and lack of effectiveness in knowledge-work organisations stems from a lack of coherence and integrity (here, in the sense of: the quality or condition of being united, whole or undivided; completeness.)

Further Reading

On Being A Therapist – An Interview with Jeffrey Kottler (article)

Transactional Analysis (Eric Berne)

Transactional Analysis (“TA”) is an integrative approach to the theory of (individual) psychology and psychotherapy. TA places an emphasis on curing the patient (relieving them of their neuroses or psychoses), rather than just understanding them (or having them understand themselves).

I find TA has significant applications in the context of organisational psychotherapy, for example the role the organisation too often plays as Parent in relation to its employees-as-Children. Note: The TA roles are reinforced from early an early age by our traditional systems of education.

Further Reading

Families and How to Survive Them ~ Robin Skynner and John Cleese

I’m OK, You’re OK ~ Thomas Anthony Harris

General Semantics (Korzybski)

Count Alfred Korzybski founded the field of General Semantics, and in particular the premises of:

- Non-Aristotelianism

- Time Binding

- Non-elementalism

- Infinite-valued determinism

“We need not blind [and bind] ourselves with the old dogma that ‘human nature cannot be changed’, for we find that it can be changed.”

~ Alfred Korzybski

Drawn from his work with General Semantics, D David Bourland, Jr. created E-Prime to address the “structural problems” – as determined by Korzybski – of using various forms of the verb “to be”. I find E-Prime to be (sic) a useful addition to the Organisational Psychotherapist’s toolkit.

Further Reading

Science and Sanity: An Introduction to Non-Aristotelian Systems and General Semantics ~ Alfred Korzybski

The Institute of General Semantics – Home page

Action Research, Force Field Analysis (Kurt Lewin)

“Action research is a term which refers to a practical way of looking at your own work to check that it is as you would like it to be. Because action research is done by you, the practitioner, it is often referred to as practitioner based research; and because it involves you thinking about and reflecting on your work, it can also be called a form of self-reflective practice. The idea of self reflection is central. In traditional forms of research – empirical research – researchers do research on other people. In action research, researchers do research on themselves. Empirical researchers enquire into other people’s lives. Action researchers enquire into their own.”

~ McNiff, 2002

Kurt Lewin is known as one of the modern pioneers of social psychology, industrial and organisational psychology, and applied psychology, including Group Dynamics, Action Research and Organisational Development. He specified Lewin’s Equation for behaviour: B=ƒ(P,E).

Force field analysis provides a framework for looking at the factors (forces) that influence a situation

“In the late 1930s Kurt Lewin and his students conducted quasi-experimental tests in factory and neighbourhood settings to demonstrate, respectively, the greater gains in productivity and in law and order through democratic participation rather than autocratic coercion. Lewin not only showed that there was an effective alternative to Taylor’s ‘scientific management’ but through his action research provided the details of how to develop social relationships of groups and between groups to sustain communication and co-operation… Action research was the means of systematic enquiry for all participants in the quest for greater effectiveness through democratic participation.”

~ Clem Adelman

Chris Argyris acknowledges the roots of his “Action Science” (co-developed with Robert W. Putnam) in Lewin’s Action Research (and in the work of John Dewey).

Further Reading

Kurt Lewin and the Origins of Action Research ~ Clem Adelman (pdf)

Leadership and the New Science ~ Margaret Wheatley

Thinking Environments (Nancy Kline)

Nancy Kline, in her book “More Time to Think“, makes the case for creating a “Thinking Environment”, and identifies a number of “components” (with associated techniques) to help achieve this:

- Attention

- Equality

- Ease

- Appreciation

- Encouragement

- Feelings

- Information

- Diversity

- Incisive Question

- Place

Other Influences in my Practice

- Patrick Lencioni (Trust, team-building)

- Dan Pink (Intrinsic Motivation)

- Morihei Ueshiba (Aikido philosophy, harmony)

- Buddha (Zen)

- Lao Tsu (Taoism)

- Gandhi (Compassion, nonviolence, integrity)

- Karl Marx, Georg Hegel (Alienation)

- CBT (Cognitive Behavioural Therapy)

- REBT (Rational Emotive Behaviour Therapy – Albert Ellis)

- Mark Federman and the concept of Ba

– Bob