How to Spot a Lemon Consultant

A Lorra, Lorra Lemons

In my time I have seen a lot of lemons. And I have seen a lot of companies hire or engage with lemons – almost always unwittingly. Actually, I can’t believe how ineffective some of these folks and suppliers have been. And let’s face it, there’s a lorra, lorra lemons out there.

Following on from my recent “Better Customers” post, I thought it might offer some value to share some tips on how to spot these lemons.

The Lemon Consultant

Description

The Lemon Consultant is most often a pinstripe- or blue-suited individual – through its colouration and demeanour attempting to appear native amongst the local dominant fauna.

The Lemon Consultant strides purposefully from place to place, exuding faux-charm and confidence in an effort to attract its prey. Juveniles are similar to adults except the suits are cheaper and the veneer of confidence thinner, with a tinge of bluster.

Lemon Consultants prefer to congregate in flocks, for security and mutual support, although solitary individuals are also sometimes seen in the wild.

Range and Habitat

Lemon Consultants prefer surrounding of glass, steel and laminate, and favour smaller, private spaces over the open savannah. They are common in urban and suburban areas especially where large budgets are predominant.

Throughout the summer Lemon Consultants can be found in most of the major conurbations across the Northern Hemisphere. In North America: from southern Canada, down through the United States to the Mexican border. There are small pockets of Lemon Consultants as far west as Washington State. In Europe: preferring temperate climes, they are fewer in Scandinavia and Mediterranean countries, with a significant population in the British Isles.

They are partially migratory with some migrating and others not. Some Lemon Consultants migrate quarterly, but always preferring to stay in one place for as long as their food source remains plentiful.

Nesting Habits

Like Mourning Doves, Lemon Consultants often take over other’s nests, at least temporarily. Failing that, and like the Black-headed Grosbeak, Lemon Consultants are known to steal parts and pieces of others’ nests to construct their own. In settled (non-migratory) situations, Lemon Consultant prefer a burrow or other cosy corner where they can keep out of sight whilst preening.

Feeding and Watering

Whilst Lemon Consultants are omnivorous, they prefer hard cash up front. When such pickings are scarce, they often settle for an hourly rate. They have been known to travel incredible distances from their breeding grounds to their preferred feeding sites. Avaricious and self-serving, the Lemon Consultant concerns itself predominantly with feeding.

Lemon Consultants do a wonderful job of regurgitating ideas from other sources, although generally poisoning the seeds and causing the resulting crop of ideas to be stunted and malodorous.

Song

The Lemon Consultant is a very vocal bird. It often has a strident, even whining note, although some few have a lilting, musical overtone. They make a number of different calls including its distinctive “deliver-cost-urgency”. It growls when it’s irritated, and chatters when it’s not. The Lemon Consultants has whistles and gurgling sounds in its repertoire as well.

Behaviour

The Lemon Consultant is often both aggressive and territorial. Group of Lemon Consultants will attack intruders and other Consultants that move into their territory, although they take great pains to avoid overt conflicts, preferring stealth and subversion to direct assaults.

If the weather is mild and the food plentiful, Lemon Consultants may winter over in their breeding grounds. But when they do migrate, they form loose flocks of around 3 to 12 traveling only during hours of darkness.

Sub-species

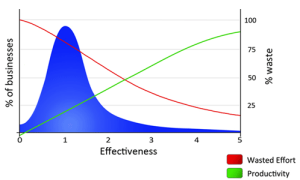

The lesser-known Lemon Agile Consultant can be distinguished from its more common brethren by its naivety, good-naturedness, and a fondness for making grandiose claims about the benefits of Agile software development whilst making no mention of the risks, costs, or the scale of changes required throughout adopting organisations.

The Lemon Agile Consultant is also very fond of Powerpoint presentations featuring cutesy child-like artwork and banal, empty platitudes; specious and tiresome “games”; often carries copious amounts of Lego; and repeats words like “fun”, “fairies” and “the power of stories” ad-nauseam.

Their song varies subtly from their common cousins, their most distinctive calls including “fun-clap-fun”, “more-value-less-waste” and “time-to-market”. Listen to the song of the Lemon Agile Consultant: Sound Bites: Lemon Agile Consultant, National Twat Service

Lemon Agile Consultants frequently borrow ideas from primary sources, but often out of context, and having grasped the wrong end of the stick. Their attribution of sources is rare to non-existant.

The Lemon Agile Consultant enjoys playing, and wants to play in your sandpit, with your money and your resources. Their gregarious nature means they love to rope-in as many of your people as possible, regardless of the distraction and disruption this causes. Outcomes rarely hold their interest for long, if at all.

Recognition

Recognising Lemon Agile Consultants amongst the general fauna is relatively simple. Ask direct questions like:

- What’s most likely to happen when we roll agile out across the whole development group?

- How will adopting Agile impact on other groups within the organisation?

- What will we have to do to realise the promised benefits of Agile over the longer term (i.e. beyond 9-15 months)?

- What are the key elements for ensuring our investment in Agile is sustainable and does not dissipate when e.g. early sponsors and champions leave the organisation?

- How have Agile adoptions turned-out in other organisations? Well? Badly? What’s the typical success rate, longer-term? What are the likely pitfalls?

- Is Agile suited here? Are there approaches other than Agile that can meet our needs as well or better?

Note: The nature of the answers are less important than having answers. The typical Lemon Agile Consultant will struggle, both with understanding the very questions, and in finding convincing answers.

Further Resources

Summary

Avoiding Lemon Consultants may seem like a difficult challenge, and for the uninitiated it can be. But with just a little awareness, a little patience to pass them by, and a few simple rules of thumb, it gets much easier. And if life throws you one or more of these Lemon Consultants? Don’t bother even trying to made lemonade. Lemon squash, maybe.

– Bob