One Principle, One Agendum

On the face of it, my most recent job was very different to some other gigs I’ve had over the years. A Novice Analytic organisation, trying hard to become Competent Analytical and spending untold millions of pounds in the process – on things like policies, structure, controls, compliance and the whole nine yards.

On the face of it, my most recent job was very different to some other gigs I’ve had over the years. A Novice Analytic organisation, trying hard to become Competent Analytical and spending untold millions of pounds in the process – on things like policies, structure, controls, compliance and the whole nine yards.

The Problem

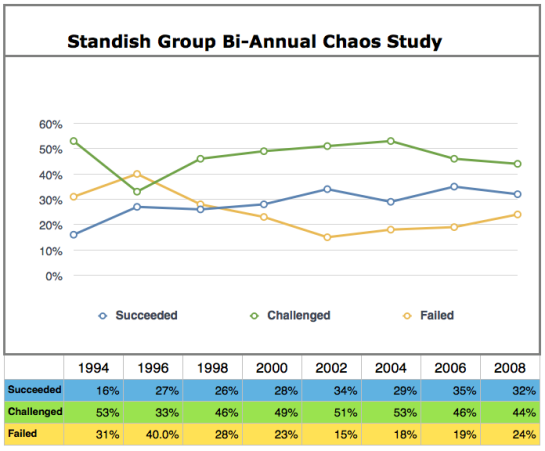

The immediate problem was the borkedness of the organisation’s whole approach to software and tech product development. Like so many other organisations, quality was low, deadlines regularly and repeatedly missed, costs out of line with expectations – the usual problems.

The Answer

Yet “the answer” was, as ever, summed up by the Antimatter Principle:

“Attend to folks’ needs.”

Of course, given the nature of the organisation, there was from the outset a fundamental question as to whether this was going to fly, and after some six months it had become patently clear that the answer was “no”.

The folks holding the reins – and the purse strings – appeared unable to transcend their existing beliefs and assumptions, even as it meant they were frustrating their own needs being met. Not to mention the needs of e.g. customers, shareholders, and employees.

One Principle

I’ve written several posts recently about the Antimatter Principle. This one principle is all any knowledge-work organisation need adopt. All things, all beneficial outcomes, can flow from a focus on this one principle. I suspect most folks don’t even begin to understand just how much of a sea change this is. Or maybe most folks believe that, like in my recent job, it’s never going to fly. Well, many things we see in the workplace now were once inconceivable. And ineffectiveness remains the rule throughout organisations of all kinds. Isn’t finding better ways what we’re focussed on? At least, for some of us? Personally, I’d much prefer working with those very few organisations where it could fly, today.

“Everything in Theory of Constraints comes down to one word: FOCUS.”

~ Eliyahu M. Goldratt

Similarly, one could say that – from the perspective of the Antimatter Principle – everything in making knowledge-work organisations more effective comes down to one word: NEEDS.

One Agendum

Implicit in the Antimatter Principle is but one agenda item: When we attend to everyone’s needs – including, don’t forget, our own – everything else takes care of itself. Or more exactly, everything else – all needs, of all folks – is taken care of by those folks. If some folks need effective services delivered to them by others, that’s what happens. If some folks need to see things improving, folks attend to that.

Modus Operandi

Neither “big change”, nor “start with the status quo”, but “start where folks feel they need to start, and change as quickly or as slowly as folks feel they each – and collectively – need to change”.

Predicated

The healthy and effective application of the Antimatter Principle – if some folks need it applied healthily or effectively – is predicated on folks acquiring skills in e.g. meaningful dialogue and humane relationships. In a circular fashion, the Antimatter Principle – even from the outset, when folks may be quite unskilled – will contribute to the acquisition of those skills – as and when needed.

Conflict

Some people have asked me what happens when different folks’ needs are in conflict. For me, this is a non-question, assuming as it does that folks will pursue their own needs at the expense of others’.

“What people enjoy more than anything else is willingly contributing to each other’s wellbeing.”

~ Marshall Rosenberg

Try this short thought experiment:

Think of an occasion recently when you’ve done something that has enriched some else’s life. How does it feel right now to be conscious you have this power to contribute to people’s well-being? Can you think of anything in the world that’s more enjoyable than contributing to people’s wellbeing?

I share the NVC view that:

“Compassionate giving is what people MOST enjoy doing.”

New Frame

I’ve written recently about the Antimatter Principle being a profoundly new frame. Marshall Rosenberg sums this up well:

“We need as a society to have a different consciousness, based on ‘compassionate giving’.”

~ Marshall Rosenberg

The Commercial Angle

If you’ve managed to read this far without clicking away in disgust or exasperation, I’d like to close this post with a few words about the commercial angle. Most businesses exist (ostensibly) to make money. Even those who dispute this – such as Russell Ackoff, Bill Deming, and Art Kleiner – suggest other reasons for businesses to exist. In any case, I’m no hippy idealist, pleading for humanity (just) on the basis of moral or ethical arguments. Rather, I have seen so many times, in so many organisations, what happens when people’s needs are ignored – and what CAN happen when folks needs receive the focus of everyone’s attention. Outcomes (profits, status, lifestyles, or whatever we can agree is the goal) improve massively when folks come together as an active community engaged in compassionate giving. And the outcome that most occupies me – the realisation of human potential – is massively increased, too.

Awakening

I remain flabbergasted at the number of organisations and people – executives, managers and workers all – who fail to realise this. Or choose to ignore it. It’s the world we live in, I guess.

“When I look at the world I’m pessimistic, but when I look at people I am optimistic.”

~ Carl Rogers

I remain hopeful that one day – please, oh please let it be one day soon – folks will wake up to the amazing possibilities at the heart of the Antimatter Principle. How about you? Have you awoken?

– Bob