Holistic Solutions for Product Development Businesses

Several people have been in contact this week to say “It’s all very well talking about holistic solutions for software development, but who really has any notion of what that might even look like?”

Which is a fair question.

Aside: Let’s note that the phrase “holistic solution for software development” is an oxymoron of the first order. By definition, software development is but part (and generally a small part) of any solution that addresses customer or market needs. Even software “pure plays” have a lot of non-software components.

So, I thought I’d describe just one holistic solution for whole organisations that develop new products containing some software. For want of a better name, I’ll call it this example “Flow•gnosis”. With this example, I hope that maybe one or two readers might find a spark of insight or inspiration to broach the question of a True Consensus in their own organisation.

I’ll try to keep this post brief. I’d be happy to come talk with you about holistic product development solutions for organisations, in person, if you have any real interest.

Flow•gnosis?

Flow•gnosis is a hybrid born of FlowChain and Prod•gnosis. FlowChain is not specifically a holistic solution, focussing as it does on improving the flow of knowledge work through a development group or department whilst moving continuous improvement “in-band”. Prod•gnosis is specifically a holistic solution for effective, organisation-wide product development, but says little about how to organise the work for e.g. improved flow or continuous improvement.

Together, they serve as an exemplar of a holistic solution for knowledge-work organisations, such as software product companies, software houses, tech product companies, and organisations of every stripe with in-house product development needs.

Let’s also note that Flow•gnosis is just an example, to illuminate just a few aspects of a holistic solution. Do not under any circumstances consider copying it or cloning it. Aside from the lack of detail presented here, you’d be missing the whole point of the challenge: building a True Consensus, as a group, with your people, in your context.

What’s the Problem?

Before talking more about a solution, what’s the problem we’re trying to solve?

I’ll work through an almost universal problem facing organisations that “do” software development. A problem that some enterprising supplier or management team might choose to address with an “innovative” solution.

Understanding the Problem

Here are some typical Undesirable Effects (UDEs) I hear from many companies involved in software and product development:

UDE: Delivery is not fast enough (long time-to-market)

UDE: New products cost too much to develop (high cost to bring to market)

UDE: We struggle to keep our products at the cutting edge

UDE: We always drop balls in hand-offs of tasks (i.e. between specialists, or business functions)

UDE: Continual contention for in-demand specialists

(For the sake of brevity, I’ll skip the building and analysis of the cause and effect graph. Your analysis will be different, in any case).

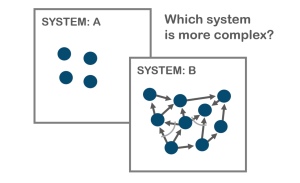

Root cause: Developing new software, products and services through a byzantine labyrinth of tasks and hand-offs, between and across dozens of specialisms within the company and its network of suppliers and distributors. This approach causes many delays (waste of time), mistakes (waste of effort, money), contention of resources, etc.

Conflict: A) Specialists must work together in their own specialist groups or silos to maintain their cutting-edge skills and know-how. B) Specialists from across all specialisms must work together as a group else handoffs and queues will cause many delays and mistakes.

Conflict arrow: Specialists cannot work in their own groups advancing their specialist knowledge at the same time as they work together with other kinds of specialist on new product ideas.

Flawed assumption at the root of the conflict: Specialists must work together. What makes this so? Only the old rules of the organisation. That silos (a.k.a. business functions) “own” their clutch of specialists. What if we changed that rule? (Note: this change is one key element of Toyota’s TPDS). And if we changed that rule, what other rules would we need to change too?

A Bird’s Eye View of Flow•gnosis

Prod•gnosis looks at an organisation as a collection of parallel Operational Value Streams, each dedicated to the selling and support of one of the organisations’ (whole) product or service lines. And each with its own team or collection of people doing the daily work of that operational value stream. Further, Prod•gnosis asks “How do these operational value streams come into being?” And answers with “They are made/created/developed by a dedicated Product Development Value Stream.”

FlowChain describes a way of working where a pool of self-organising specialists draws priority work from a backlog, executes the work, and delivers both the requested work item, and posting new work items (for improving the ways the work works) into the backlog. In this way, FlowChain both improves flow of work through the system, and brings continuous improvement “in-band”

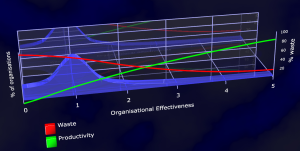

By merging Prod•gnosis and FlowChain together into Flow•gnosis, we have an organisation-wide, holistic example which improves organisational effectiveness, reifies Continuous Improvement, speeds flow of new products into the market, provides an operational (value stream based) model for the whole business, and allows specialists from many functions to work together with a minimum of hand-offs, delays, mistakes and other wastes.

The latter point is perhaps the most significant aspect of Flow•gnosis. Having customer, supplier, marketing, sales, finance, logistics, service, billing, support and technical (e.g. software, usability, emotioneering, techops, etc.) specialists all working together (cf. Toyota’s Obeya or “Big Room” concept) enables the evolution of “Mafia Products” and “Mafia Offers” which the more traditional silo-based models of business organisation just can’t address effectively.

Out With the Old Rules, In with the New

Flow•gnosis is an innovation. Irrespective of the promised benefits of Flow•gnosis, we have learnt in recent posts that adopting an innovation ONLY brings benefits when we change the rules.

Let’s apply the four questions to our Flow•gnosis innovation and see what rule changes will be necessary to truly reap the benefits.

Q1: What is the POWER of Flow•gnosis?

A1: Flow•gnosis makes it commercially feasible for a company to repeatably come to market with new “Mafia Products”.

Mafia Product: “A product (or service) so compelling that your customers can’t refuse it and your competition can’t or won’t offer the same.”

Q2: What limitation does Flow•gnosis diminish?

A2: Serialisation of specialist work (passing things back and forth between various specialist and business functions).

Q3: What existing rules served to help us accommodate that limitation?

A3: Handoffs. Queues. Batches. Separation of command and control from the work. Process. Process conformance. Local measures. Constant expediting. Critical path planning (Gannt charts, WBS). Local optima. Functional management (discrete management of each separate business function).

Q4: What (new) rules must we use now?

A4: Flow. Value streams. SBCE. Holistic measures. Ubiquitous information radiators. Cost Of Delay prioritisation. Buffer management. Constant collaboration. Dedicated teams of generalising specialists. Self-organisation. In-band continuous improvement. Resource levelling. Limits on WIP.

Summary

This post has been a – necessarily brief – look at one holistic solution to (software) product development. Crucially, we have seen how old rules have to be replaced, and what many of the replacement new rules might look like.

I invite you to remember that Flow•gnosis is just an broad-brush example of a holistic solution. Please don’t consider copying it or cloning it. And remember the real challenge: building, as a management group, a True Consensus.

– Bob

Further Reading

Meeting Folks’ Needs At Scale – Think Different blog post