R.D. Laing: Challenging Society’s Views on Madness

Ronald David Laing (1927-1989) was a Scottish psychiatrist known for his unorthodox and radical views on mental illness. Though trained as a psychiatrist, Laing rejected the medical model of mental disorders, arguing instead that psychosis and schizophrenia were understandable responses to an “insane world”.

Views on Mental Illness

Laing’s views on mental illness were heavily influenced by existential philosophy and thinkers like Kierkegaard and Sartre. He rejected the idea that psychiatric conditions like schizophrenia were medical diseases and argued they resulted from difficulties in developing a coherent sense of self in response to invalidating family and social environments.

In his 1960 book The Divided Self, Laing argued that psychotic behavior and experiences made sense as strategies to cope with living in an “insane world” where individuals cannot express their true feelings and spontaneity is suppressed. He argued mental distress resulted from societies that emphasised conformity over creativity and adjustment over authenticity.

Laing criticised psychiatric diagnoses and medications as unethically labeling and controlling people rather than understanding them. He preferred to use talk therapy to try to understand his patients’ perspective and believed schizophrenia could represent a transformative spiritual crisis rather than just a brain disease.

Sanity in an Insane World

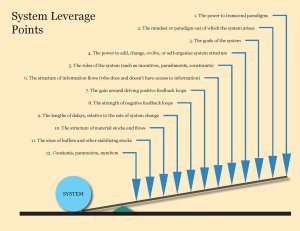

Laing’s famous statement that “Insanity is a perfectly rational adjustment to an insane world” encapsulated his argument that much of what is defined as mental illness by mainstream psychiatry is actually a understandable response to dysfunctional families and societies.

In his 1967 book The Politics of Experience, Laing wrote: “It is no measure of health to be well adjusted to a profoundly sick society…What we call ‘normal’ is a product of repression, denial, splitting, projection, introjection and other forms of destructive action on experience.”

Laing believed that focusing on listening to and understanding those labeled mentally ill, rather than automatically treating them as diseased, could transform society’s conception of sanity. Through his psychotherapy practice and writings, he aimed to legitimize the inner experiences of those with psychiatric diagnoses.

Insanity is the Norm

One of Laing’s most radical arguments was that what society considers “normal” is itself a form of insanity or mental illness. In The Politics of Experience, he wrote:

“Our ‘normal’ ‘adjusted’ state is too often the abdication of ecstasy, the betrayal of our true potentialities, many of them so special and so dangerous to the social order.”

Laing believed that modern societal pressures and conformism force individuals to alienate themselves from their true feelings, impulses, and experiences. The result is an inauthentic existence cut off from the spontaneous, creative core of human nature.

He argued that the inner vivid world experienced by those labeled “schizophrenic” or “psychotic” is not qualitatively different than the inner world of “normal” individuals. The so-called psychotic person has simply lost the ability to conceal this inner world from others.

Laing contended that the “normal” person’s concealed inner world was just as chaotic, frightening, and beautiful as that experienced by those diagnosed with mental illness. But it is suppressed to maintain societal approval. In contrast, the “insane” allow their authentic inner selves to manifest outwardly.

By Laing’s definition then, the majority who view themselves as sane or normal are in a state of socially-imposed constraint that alienates them from the depths of human consciousness. The “insane” minority have touched these terrifying and visionary depths that society fears. As Laing wrote, “Madness need not be all breakdown. It may also be break-through.”

Legacy and Impact

Laing’s work challenged mainstream beliefs about mental illness and who has the authority to define sanity. His ideas influenced the anti-psychiatry movement, which argued psychiatric treatments were often more damaging than helpful. Though controversial, Laing’s work encouraged the public to rethink assumptions about mental distress and gained more compassion for those viewed as mentally ill. His legacy lives on in efforts to reform mental health services to be more humane and empowering.