Silos

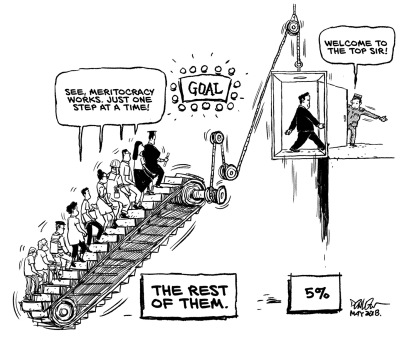

For anyone who has worked in organisations, whether large or small, the phenomenon of workplace “silos” is all too familiar. Silos refer to the tendency for different departments or teams to operate in isolation, with little communication or collaboration between them.

While most folks working in the tech industries are familiar with the pitfalls of organisational silos such as separate marketing, sales, and operations teams, few recognise the similarly damaging effects of silos between disciplines.

For example, often, software engineers operate in isolated codebases, data scientists in segregated modeling pipelines, and designers in siloed UI frameworks. This compartmentalisation breeds many of the same pathologies as organisational silos:

- Lack of big-picture perspective

- Shortfalls in creative insights into how the work works, and could work better

- Duplicated efforts

- Limited knowledge sharing and innovation

- Rigid mental models resistant to change

Yet modern tech products and services require integrating numerous disciplines – systems thinking, the theory of knowledge, understanding of variation, and psychology, as well as the more usual specialsms: programming, data, design, DevOps, product management, and more. When disciplines remain cloistered, the resulting solutions are sub-optimal.

The Power of Multi-Disciplinary Collaboration

In contrast, forging multi-disciplinary collaboration unlocks a powerful union of diverse skills, perspectives and domain knowledge. As Deming highlighted in his System of Profound Knowledge, viewing problems through a wide aperture leads to deeper insights.

Some key benefits of this cross-pollination include:

- End-to-end alignment on objectives across the value chain

- Dynamic combination of complementary expertise areas

- Faster issue resolution by aligning priorities holistically

- Continuous learning and growth for all

- Fostering an innovative, psychologically safe culture

Rather than optimising isolated components, multi-disciplinary collaboration enables the co-creation of cohesive products and experiences that delight all the Folks That Matter™.

Cultivating Multi-Disciplinarity

Of course, nurturing this multi-disciplinary ideal requires organisational support and the rethinking of ingrained assumptions and beliefs about work. Incentive structures, processes, and even physical workspaces will need redesigning.

But the potential rewards are immense for forward-looking companies – accelerated innovation cycles, more productive ways of working, and formulating solutions beyond what any individual narrow-discipline specialist could achieve alone.

In our age of relentless disruption, the greatest existential risk is insular thinking – holding too tightly to narrow disciplines as the world shifts underfoot. Multi-discipline dynamism, powered by collective knowledge and continuous learning, is the currency of sustained advantage.

For those willing to transcend boundaries and embrace profound cross-discipline pollination, the possibilities are boundless. Those clinging to compartmentalised organisational and disciplinary silos, however, face morbid irrelevance.

Deming’s SoPK

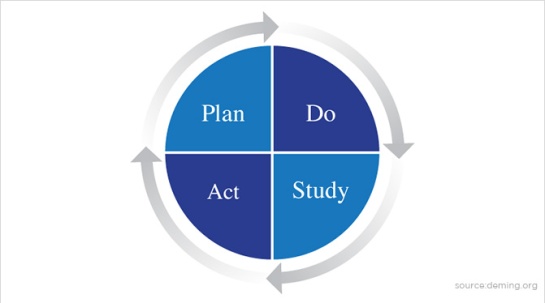

For decades, W. Edwards Deming advocated his “System of Profound Knowledge” (SoPK) as the key to transforming businesses into continuously improving, customer-focused, multi-disciplinary organisations. At its core are four interdependent principles that combine heretofore disparate disciplines:

- Appreciation for a System: Understanding that an organisation must be viewed as an interconnected system, not just isolated silos. Each part impacts and is impacted by others.

- Theory of Knowledge: Recognising that learning and innovation arise from the synthesis of diverse theories, concepts and perspectives across domains.

- Knowledge about Variation: Grasping that complex systems involve inherent variation that must be managed holistically, not through narrow inspection alone.

- Psychology: Harnessing intrinsic human motivations and driving participation, rather than extrinsic forces like punitive accountability.

In most organisations, none of these profound knowledge principles are well known, let alone deeply embraced, appreciated and systematically applied. They represent a radical departure from traditional siloed thinking.

When applied holistically, Deming’s SoPK philosophy exposes the many drawbacks of organisational disciplinary silos, including:

- Lack of big-picture, end-to-end perspective

- Redundancies and inefficiencies from duplicated efforts

- Suboptimal solutions from narrow specialisations

- Fragmented vision and strategy misalignment

- Resistance to learning and change across boundaries

Deming’s philosophy highlights the advantages of multi-disciplinary collaboration to optimise systems holistically. Narrow specialisation alone is dysfunctional.

By shining a light on these drawbacks upfront, the importance of breaking down counterproductive disciplinary silos becomes even more stark. The vital need for collaboration, systems-thinking, applied psychology and profound cross-domain knowledge is clear across all disciplines and value chains.

By highlighting these drawbacks upfront, the importance of breaking down counterproductive silos becomes even more stark. The need for collaboration, systems-thinking, applied psychology and profound knowledge cuts across all disciplines.

The System View: Beyond Isolated Parts

Deming’s first principle stresses that an organisation may be viewed as an interconnected system, not just as separate silos or departments working in isolation. Each group’s efforts affect and are affected by other parts of the system.

Silos represent a fragmented, piecemeal view that is anathema to systems thinking. By reinforcing barriers between marketing, sales, engineering, operations and more, silos prevent the shared understanding required for optimising systems as a whole.

Knowledge Through Diverse Perspectives

According to Deming’s Theory of Knowledge, continuous learning and improvement stems from the interplay of diverse theories, concepts and perspectives. Innovation arises through making connections across different mental models and multiple disciplines.

When teams comprise members from various disciplines, their unique backgrounds and experiences foster richer exchanges of knowledge. Silos, in contrast, restrict the cross-pollination of ideas.

Understanding Variation

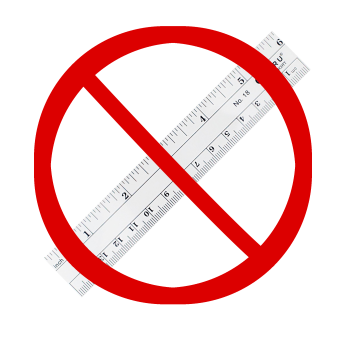

Deming’s view of variation exposes the fallacy of trying to eliminate every defect or failure through e.g. mass inspection. Complex systems involve inherent variation that must be managed holistically, not narrowly inspected away.

Multi-discipline teams can better grasp the dynamic variations impacting their shared objectives, drawing on complementary viewpoints to guide iterative learning.

Harnessing Psychology for e.g. Motivation

Finally, Deming emphasised the power of harnessing people’s intrinsic motivations, rather than relying on punitive accountability within silos (or communities of practice). When experts from various domains unite on meaningful projects, it cultivates broader purpose and drives discretionary effort.

By removing restrictive boundaries, multi-disciplinary collaboration enables self-actualisation while encouraging collective ownership of outcomes.

Cultivating a Learning Organisation

For many organisations obstructed by siloed thinking, embracing Deming’s Profound Knowledge is no simple task. It requires reimagining structures, processes and even physical spaces to nurture multi-disciplinary engagement.

Yet the potential rewards are immense – from accelerated cycles of innovation and organisational agility, to a workforce invigorated by joy, pride, and deeper fulfilment in their day-to-day. Deming’s wisdom reveals the collaborative imperative for thriving amidst volatility.

The greater risk lies not in disruption itself, but in calcifying into rigid, inward-looking organisational and disciplinary silos incapable of evolving. Organisations have a choice: cling to the illusion of control through silos and narrow specialisms, or embrace the profound knowledge gained by breaking boundaries.