The Shrink is IN

I have struggled for many years to find a model for positive and effective engagement with organisations looking to improve their effectiveness. Agile coaching has not worked for me – or for clients, much – because of its generally limited (i.e. individual, team or departmental) scope. Ditto Scrum Mastering (and this compounded by a widespread misconception about what Scrum Mastering even means, and just why it might offer any value).

Consulting likewise misses the mark, not least because clients rarely understand how to get anything like the best out of consultants and consulting advice. It’s often like the organisation needs consulting on how to use consultants. Of course great consultants should and can do this – clients permitting – but Sturgeon’s Law tells us these folks are rare.

So I’ve been on the lookout for a model of engagement that affords the following opportunities:

- Models positive behaviours, such as fellowship, mutual respect and collaboration.

- Promotes introspection and self-renewal, allowing folks to find their own way.

- Respects the individual.

- Avoids compounding common dysfunctions, such as parent-child dynamics (c.f. Transactional Analysis) and alienation.

- Replaces dependency and learned helplessness with self-reliance and self-confidence.

- Congruent with positive psychology (i.e. PERMA): Positive emotions, Engagement, Relationships (social connections), Meaning (and purpose) and Accomplishment.

- Offers incremental and tangible progress at a pace set by the folks involved.

- Therapeutic (i.e. healing, curative, but also sometimes preventive or supportive).

- Social and humane.

Accordingly, I have come to regard “therapy” as a model closely matching these attributes, and specifically, “psychotherapy“. But, from a systems thinking perspective, the clients or “patients” are not the individuals in an organisation, but the organisations themselves.

So these days I choose to call myself an “Organisational Psychotherapist”. What does that mean, exactly? What does Organisation Psychotherapy look like in practise? And how can an approach founded on the principles of therapy help organisations improve their effectiveness?

Aside: We have to assume that an organisation wants help, wants to improve its effectiveness (or maybe some other aspect of its “personality”, functioning, or well-being). If thirty years of coaching has taught me one thing, it’s that there’s no helping folks (or organisations) that don’t want to be helped.

Why Therapy?

Maybe the first question folks have is “why therapy?”. Why take a therapy stance when most other folks choose to act as consultants, or coaches? Fundamentally, it’s because I believe an organisation, as a whole, has to work its issues through, and take responsibility itself for doing that. Too often, consultants get hired to shoulder responsibility on behalf of the organisation. And when these consultants leave, clients all too often find themselves back at square one – or worse. Like a game of Snakes and Ladders.

So, to organisational psychotherapy. As an analogy, we might consider the work of Virginia Satir, widely regarded as the “Mother of Family Therapy”.

“Families and societies are small and large versions of one another. Both are made up of people who have to work together, whose destinies are tied up with one another. Each features the components of a relationship: leaders perform roles relative to the led, the young to the old, and male to female; and each is involved with the process of decision-making, use of authority, and the seeking of common goals.”

~ Virginia Satir, Peoplemaking, ch. 24 (1988).

“It is now clear to me that the [organisation] is a microcosm of the world. To understand the world, we can study the [organisation]. Issues such as power, intimacy, autonomy, trust, and communication skills are vital parts underlying how we live in the world. To change the world is to change the [organisation].

~ Virginia Satir (paraphrased)

The New Peoplemaking, ch. 1 (1988)

Organisational Psyche

In The Nine Principles of Organisational Psychotherapy, I stated as principle 3:

3. Organisations Have a Collective Psyche that Responds to Therapies

Organisational therapy procedes on the basis that the collective psyche of an organisation is similar in nature to the psyche of the individual, and is similarly amenable to therapeutic interventions (although the actual techniques and underlying concepts may differ).

That’s to say, the collective consciousness of an organisation is a thing in its own right, and we can examine it, interact with it and (help) alter it, for better – or worse.

“…the qualities that all human beings need and yearn for in other humans, a sense of being cared for, valued, wanted, even loved…what for a lifetime, human beings strive to find. Some of the most important : empathic concern, respectfulness, realistic hopefulness, self-awareness, reliability and strength – the strength to say ‘yes’ and the strength to say ‘no’.

~ Stanley S. Greben

I believe organisations, too, need these qualities. All too often organisations – in part or as a whole – come to regard themselves with some degree of self-loathing.

Where’s the Value?

Paul DiModica, in his excellent book “Value Forward Selling” suggests that people appreciate a clear communication of the value of an idea or proposition. To that end, here’s what I believe is the (unique) value in taking a therapy stance with respect to e.g. improving organisational effectiveness (a.k.a. Rightshifting):

The organisations with which I work consider therapy because some aspect or aspects of their “cognitive (brain) functioning” is not working as well as they would like. Despite these organisations’ basic competence, they have not been able to resolve these issues to their own satisfaction, from their own resources.

With improved functioning comes an improved ability to cope, to grow, to mature, and to build necessary capabilities. And with these comes increasing effectiveness, revenue growth, margins, and customer, employer, employee and shareholder satisfaction. Not to mention organisations which are able to play a more positive role in wider society.

How Does It Feel?

So, what does it look like and feel like to be an employee of an organisation that has chosen to work with an organisational therapist?

Firstly, it’s probably useful to understand that therapy does not try to “fix” anyone or anything. Personally, I most often choose to approach a new engagement from a perspective akin to Solution Focused Brief Therapy:

“SFBT focuses on what [the client organisation] wants to achieve through therapy, rather than on the problem(s) that made it seek help. The approach does not focus on the past, but instead, focuses on the present and future. The therapist/counselor uses respectful curiosity to invite the client to envision their preferred future and then therapist and client start attending to any moves towards it – whether these are small increments or large changes.”

Given that we’re talking about organisational therapy, there’s the added dimension of working with many different folks within the client organisation – as opposed to working with just one person in individual therapy, or maybe half-a-dozen or so people, in family therapy situations.

This typically involves helping these folks improve their ability to think collectively and purposefully. I believe the key to this is the – often missing – ability to have effective, purposeful dialogue. For those (very few) organisations already skilled in this, little need to be done, but for the majority, basic work on dialogue, and thence to focus, shared visions, etc. will be required.

What to Expect From Organisational Therapy

Some folks might have some experience of one-to-one, or group, therapy. But few indeed will have had any experience of organisational therapy. Here’s a brief run-down of what folks might reasonably expect from organisational therapy.

Who Receives Psychotherapy

Most organisations, at one time or another need some help. For some organisations, talking together, and assisted by a therapist, helps them understand ways they can improve things. Sometimes organisations seek therapy at the advice of a consultant, coach, executive or investor. Sometimes it is overwhelming stress or a crisis that causes an organisation to decide to choose therapy. In addition, many times organisations might choose therapy to gain insight and acceptance about themselves and to achieve growth and improved well-being. Therapy offers these benefits to any organisation that is unhappy with the way it acts, performs or feels, and wants to change.

What Is Organisational Psychotherapy?

Organisational Psychotherapy is a relationship in which an organisation, as a whole, works with a professional in order to bring about changes in its feelings, thoughts, attitudes, and/or behaviour. The task of the therapist, therefore, is to help the organisation as a whole make the changes it wishes to make. Oftentimes the organisation entering therapy knows changes are needed but does not know what changes to make or how to go about making them. Often, too, the organisation is fragmented not used to holding an organisation-wide “internal dialogue”. The organisational psychotherapist helps the organisation figure these things out. Therapists help clients in many ways. Exactly how depends on the orientation (approach to therapy). Here the therapist’s training and beliefs on how therapy should work can have some influence. The most common therapy approaches I use are Positive Psychology, Solutions Focus, Dialogue, Scenario Modelling and Clean Language, with influences from Eastern wisdom including Buddhism, the Tao, and Zen.

Positive Psychology

“We believe that a psychology of positive human functioning will arise, which achieves a scientific understanding and effective interventions to build thriving individuals, families, and communities.”

~ Professor Martin Seligman and Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi

Positive Psychology involves the use of findings from positive psychology research. It helps organisations to change – in the ways they would like to change. Positive Positive psychologists seek “to find and nurture genius and talent”, and “to make normal life more fulfilling”. There is an emphasis in positive psychology on promoting well-being, as opposed to treating illness.

Solutions Focus

While the method and scope of the Solutions Focus approach to organisational therapy are wide-ranging and comprehensive, the basic principles are simple:

- identify what works and do more of it

- stop doing what doesn’t work and do something different.

The Solution Focused approach was developed in America in the 1980s. Two simple ideas underpin Solutions Focus organisational therapy:

- Even organisations with major dysfunctions will occasionally do good things, and achieve positive results. Solutions Focused practitioners will help uncover these exceptions – whatever the organisation is already doing, which might contribute to progress on, or resolution of the issue(s) at hand.

- Knowing where you want to get to, makes the getting there much more likely. Solutions Focused practitioners ask lots of questions about what life might be like if the problem was solved. As the answers to these questions gradually unfold the client begins to get a picture of where the organisation should be focusing.

Choosing a Therapist

“A psychoanalyst’s personality is his [or her] major therapeutic tool.”

~ Henri F. Ellenberger

You will probably want to ask potential therapists about their orientation. Ask them what this will mean for your therapy experience. Most therapists are not rigid in their orientations. You should also ask a potential therapist about use of evidence based practice. Ask them if they use methods that have been found to have evidence that they work for organisations like yours. Organisational therapy is provided in many ways, with a prevailing focus on the organisational psyche, not individuals per se.

“…it is becoming increasingly obvious that the (psycho)therapist’s personality is a more decisive factor than the school to which he belongs.”

~ Arthur Koestler

“Psychotherapy…is a craft, the aptitude for which derives more from a general experience of living than is generally supposed.”

~ Peter Lomas

What Happens in Psychotherapy?

The therapy process varies depending on the approach of the therapist. It also differs for each individual organisation, and its situation. However, there are some common aspects of therapy that organisations are likely to experience when they enter a therapy relationship.

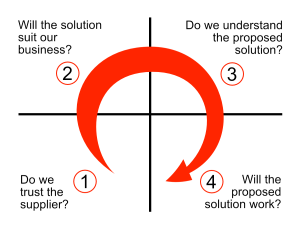

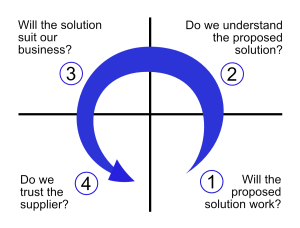

The first session with a therapist is often a consultation session. This session does not commit the organisation to working with the therapist. This session helps you to find out whether psychotherapy might be useful to you. In addition, you decide whether this particular therapist is likely to be helpful. During this session, you may want to discuss any values that are particularly important to you and your organisation. This first session is a time for you to decide if you and your organisation will feel comfortable, confident, and motivated in working with this particular therapist.

You should also feel that you can trust and respect your therapist. You should feel that your therapist understands your organisation’s situation. This is also the time for the therapist to decide whether he or she is a good match for your organisation. At times, a therapist may refer you to another therapist who may be able to work better with your organisation.

After an initial assessment stage, the rest of therapy is to help your organisation gain insight and address current problems. It can also help your organisation alter the emotions, thoughts, and/or behaviours it wants to change. The therapy process focuses on the goals which the organisation surfaces during therapy. How these goals are met depends on the orientation of the therapist and the methods the therapist may use.

Organisational therapy typically requires more activity than just talking about particular issues. These activities may include such things as role-playing or homework assignments. This is where parts of your organisation can adopt and develop the new skills it decides are valuable for the future.

The amount of therapy an organisation receives will vary depending on the orientation of the therapist and the specific treatment plan used. Some interventions are relatively short. Others require a longer time commitment.

Each session of therapy usually lasts about an hour, with members of some part of the organisation. Longer sessions, with wider participation, are also sometime advised. The therapist will generally visit with your organisation once or twice a month. However, therapy timelines are rarely rigid (or predictable). Your organisation may change the schedule to fit the needs of various groups and/or the therapist.

It is a good idea to ask your therapist about the general methods he or she may use with you in therapy. Also, ask about the length and frequency of therapy you might expect.

Some therapists suggest other treatments in addition to talking therapy. These may include workshops, off-sites, conferences, reading or other things. They may also use support groups, with members drawn from different organisations.

After a period of time, you and your therapist may agree that therapy has been successful in helping your organisation achieve its immediate goals. Even after therapy has ended, some therapists may suggest a follow-up e.g. several months later to check on how you are doing. If your organisation has new problems or feel that past problems still are not better, it may choose to return to therapy.

One important thing to remember is that all types of therapy do not automatically work for every organisation. You should always consider other options when a particular therapy is not working.

What Makes For Good Therapy?

Even as far back as the 5th Century BC, Hippocrates had apparently expressed the greater importance of studying the patient than of studying the patient’s disease.

Rather than assert my own opinion directly, allow me to share the selected views of some noted folks:

“Experience has taught me to keep away from therapeutic ‘methods’ as much as from diagnoses … everything depends on the man and little or nothing on the method.”

~ Carl Gustav Jung

“Some years ago I formulated the view that it was not the special or professional knowledge of the therapist, nor his intellectual conception of therapy (his ‘school of thought’), nor his techniques which determine his effectiveness. I hypothesised that what was important was the extent to which he possessed certain personal attitudes in the relationship.”

~ Carl R. Rogers

“…the crucial factor in psychotherapy is not so much the method, but rather the relationship between the patient and his doctor or … between the therapist and his patient. This relationship between two persons seems to be the most significant aspect of the therapeutic process, a more important factor than any method or technique.”

~ Victor E. Frankl

“…however much therapists may focus on the technical aspects of their procedures, an increasing body of evidence suggests that it is the personal relationship between themselves and their patients which is experienced by the latter as the most potent therapeutic force.”

~ David Smail

“There are many schools of psychotherapy but results appear to depend on the personal qualities, experience and worldly wisdom of the therapist rather than on the theoretical basis of the method. … There is growing evidence that effectiveness in (psycho)therapy is primarily dependent on the quality of the relationship between the quality of the relationship between therapist and patient and that, in turn, depends on the quality of the therapist.”

~ Robert M. Youngson

“If any single fact has been established by psychotherapy research, it is that a positive relation ship between patient and therapist is positively related to therapy outcome.”

~ Irvin D. Yalom

Organisational therapy works as it does because it is not a pseudo-science, magic or a kind of medical treatment, but simply because it is a highly refined method of therapeutic co-operation, both between the therapist and the organisation’s psyche, and between the folks in the organisation itself.

– Bob

Further Reading

How Psychotherapy Works ~ Online article