Key Fallacy #47 – Teaching Changes Behaviour

Key Fallacy #47 – Teaching Changes Behaviour

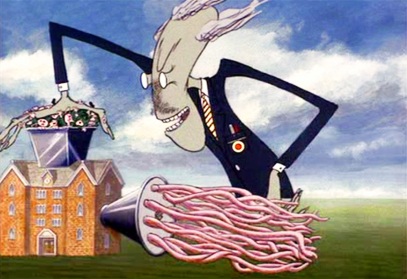

We often slip into the tempting belief that imparting knowledge is the same as instigating change. Teachers lecture, bosses dictate, and consultants advise, all under the presumption that their words, like magical incantations, will alter behaviour. But is this a groundless assumption? The answer may lie in understanding the difference between teaching and learning.

Teaching vs Learning: What’s the Real Score?

Teaching is an external process. An individual or system presents information, and the hope is that those receiving it will internalise it and act differently as a result. But teaching doesn’t guarantee learning. Learning is an internal process, something the learner does. It involves integrating new information into one’s existing knowledge base, and then applying it in a way that influences behaviour.

You Can Lead a Horse to Water…

No matter how brilliant the teaching, if the recipient doesn’t willingly engage with the material in a way that fosters understanding and application, it’s a fruitless endeavour. For real change to occur, the learner must be active in the process. They must take that information, digest it, and discover how to integrate it into their existing framework of understanding.

If behaviour hasn’t changed, then learning hasn’t happened.

The Inner Landscape

Real, lasting change occurs in the hidden corridors of the mind. It’s in the synthesising of new information with existing knowledge, in the wrestling with contradictions and the sparking of new insights, that learning manifests itself. This kind of deep cognitive processing can’t be induced by teaching alone; it’s an internal, learner-driven process.

The Efficacy of Experiential Learning

If the aim is to induce behavioural change, traditional teaching methods may not cut it. Experiential learning (a.k.a. normative learning), however, provides a more effective path. It fosters environments where individuals can experiment, make mistakes, reflect, integrate, and adapt.

Learn by Doing

The most potent learning experiences often come from making mistakes and subsequently adjusting one’s behaviour. In experiential learning, the individual is the actor, director, and the audience—involved in both executing actions and reflecting upon their outcomes.

The Role of Feedback

Another crucial component of experiential learning is feedback. Whether it comes from a mentor, peer, or is self-generated, feedback provides the raw material for reflection and behaviour modification. Without it, even the most earnest attempts at learning can go astray.

Shifting the Focus from Teaching to Learning

To see the behavioural changes we seek, we may choose to shift the focus from teaching to learning. Here are a few ways organisations can make that shift:

Cultivate a Learning Culture

Creating an organisational culture that values learning over mere instruction can lead to lasting changes. A focus on critical thinking, problem-solving, and adaptability encourages employees to be active learners.

Provide Autonomy and Resources

The more control people have over their learning process, and the more resources available to them, the more effective their learning will be. This could mean anything from providing time for self-directed learning projects to making online courses available.

Nurture Intrinsic Motivation for Authentic Learning

Rather than relying on external rewards and recognition as motivators, focus on cultivating an environment that nurtures intrinsic motivation. Alfie Kohn argues that when people are driven by their innate curiosity and passion for a subject, the learning is more meaningful, durable, and linked to positive behavioural change. Encourage exploration, critical thinking, mutuality, and the joy of discovery as the ultimate ‘rewards’ for learning. In this climate, deep cognitive processing and real understanding occur naturally, without the need for external incentives.

Summary

The gap between teaching and learning isn’t just semantic; it’s substantial. The path to genuine behavioural change lies not in the words spoken by the teacher, but in the cognitive wrestling done by the learner. Once organisations grasp this distinction, they stand a far better chance of effecting meaningful change.