I am struck by so many hiring companies claiming to be using “the latest technologies” but that make no mention of their using 100+ year old management technologies.

Marshall Model

Visual Walkthrough Explaining Rightshifting And The Marshall Model

Visual Walkthrough Explaining Rightshifting And The Marshall Model

For those who prefer looking to reading, here’s a visual explanation (with some annotations) briefly explaining Rightshifting and the Marshall Model.

1. Context: Organisational Transformation

Rightshifting illuminates the tremendous scope for improvement in most collaborative knowledge work organisations. And the Marshall Model provides a framework for understanding e.g. Digital Transformations. Don’t be too surprised if folks come to regard you as an alien for adopting these ideas.

2. Imagined Distribution of Effectiveness

How most people imagine effectiveness to be distributed across the world’s organisations (a simple bell curve distribution).

3. Contrasting Effectiveness with Efficiency

Many organisations seek efficiency, to the detriment of effectiveness.

4. If Effectiveness Were Distributed Normally

5. The Distribution of Effectiveness in Reality

The distribution of organisations is severely skewed towards the ineffective.

6. Some Corroborating Data from ISBSG (1)

7. Some Corroborating Data from ISBSG (2 – Productivity)

8. Some Corroborating Data from ISBSG (3 – Velocity)

9. Rightshifting: Recap

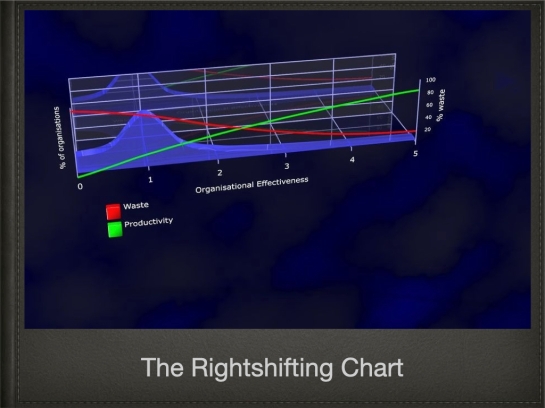

10. Plotting Levels of Waste vs Effectiveness

Showing how increasing effectiveness (Rightshifting) drives down waste.

11. Plotting Levels of Productivity vs Effectiveness

Showing how increasing effectiveness (Rightshifting) drives up productivity.

NB This the the canonical “Rightshifting Chart”.

12. From Rightshifting to the Marshall Model

Starting out with the Rightshifting distribution.

13. The Adhoc Mindset

Collective assumptions and beliefs (organisational mindset).

“Ad-hoc organisations are characterised by a belief that there is little practical value in paying attention to the way things get done, and therefore few attempts are made to define how the work works, or to give any attention to improving the way regular tasks are done, over time. The Ad-hoc mindset says that if there’s work to be done, just get on and do it – don’t think about how it’s to be done, or how it may have been done last time.”

14. The Analytic Mindset

“Analytic organisations exemplify, to a large extent, the principles of Scientific Management a.k.a. Taylorism – as described by Frederick Winslow Taylor in the early twentieth century. Typical characteristics of Analytical organisation include a Theory-X posture toward staff, a mechanistic view of organisational structure, for example, functional silos, local optimisation and a management focus on e.g. costs and ‘efficiencies’. Middle-managers are seen as owners of the way the work works, channelling executive intent, allocating work and reporting on progress, within a command-and-control style regime. The Analytic mindset recognises that the way work is done has some bearing on costs and the quality of the results.”

15. The Synergistic Mindset

“Synergistic organisations exemplify, to some extent, the principles of the Lean movement. Typical characteristics include a Theory-Y orientation (respect for people), an organic, emergent, complex-adaptive-system view of organisational structure, and an organisation-wide focus on learning, flow of value, and effectiveness. Middle-managers are respected for their experience and domain knowledge, coaching the workforce in e.g. building self-organising teams, and systemic improvement efforts.

16. The Chaordic Mindset

“The Chaordic mindset believes that being too organised, structured, ordered and regimented often means being too slow to respond effectively to new opportunities and threats. Like a modern Jet fighter, too unstable aerodynamically to fly without the aid of its on-board computers, or sailing a yacht, where maximum speed is to be found in sailing as close to the wind as possible without collapsing the sails, a chaordic organisation will attempt to operate balanced at the knife-edge of maximum effectiveness, on the optimal cusp between orderly working and chaotic collapse.”

17. Transition Zones

As organisations progress towards increasing effectiveness, they encounter discontinuities which the Marshall Model labels as Transition Zones (orange hurdles). In these transitions, one prevailing mindset must be replace wholesale with another (for example, Analytic to Synergistic, where, amongst a host of shifts in assumptions and beliefs, attitudes towards staff transition from Theory-X to Theory-Y). Cf. Punctuated Equilibria.

18. What Each Transition Teaches

A successful Adhoc -> Analytic transition teaches the value of discipline (extrinsic, and later, replaced with intrinsic).

A successful Analytic -> Synergistic transition teaches the value of a shared common purpose.

A successful Synergistic -> Chaordic transition teaches the value of “Positive Opportunism”.

19. The Return-on-Investment Sawtooth

Incremental (e.g. Kaizen) improvements with any one given mindset show ever-decreasing returns on investment as the organisation exhausts its low-hanging fruit and must pursue ever more expensive improvements.

Each successful transition “resets” the opportunities for progress, offering a new cluster of low-hanging fruit.

20. Conversation

What has this walkthrough shown you? I’d love the opportunity for conversation.

– Bob

Quickie: Borked

Conventional managers will always hire conventional managers.

Which is why software development is FUCKED.

Quickie: Ackoff Explains Analytic vs Synergistic Thinking

Here’s a video in which the great Russel L. Ackoff explains the difference between knowledge and understanding, and thereby the difference between analytic and synergistic thinking (Cf. Rightshifting and the Marshall Model).

https://deming.org/ackoff-on-systems-thinking-and-management/

Gimme A Break, Here

Gimme A Break, Here

Here I am, trying to change the world, and most days I feel like I’m being punished for the views I hold and share, and the aspirations I have. Not that it shakes my convictions, nor my resolve.

Decades

For more than two decades I’ve been trying to help everyone in the software industry get past the Software Crisis and discover new, more effective ways of doing things. And there are much more effective ways of doing things that the ways in common usage presently (see e.g. Rightshifting, and the Marshall Model).

I’ve not been having much success, I’ll admit. But I keep plugging away. I might catch a break sooner or later, surely.

The Message

My message is not “I know this stuff, do it MY way.” I’m not flogging a new method. I’m not selling anything.

My message is “The way we’ve been looking at software development for the past fifty years isn’t working. How about we find other ways to look at it? Here’s a few clues I’ve noticed…”

The Old Frame

The old frame for software development – processes and tools, the very idea of “working software” as the touchstone – holds us back and prevents us from seeing new ways of working and doing.

All our focus on technical skills, coding, design, architecture, testing, CI/CD, technical practices, canned and packaged methods, generic solutions, and etc. has had us barking up the wrong tree for more than half a century.

And the almost ubiquitous centuries-old management factory hasn’t helped us make the transition.

The New Frame

I’ve written before about the new frame, but to recap:

The new frame that my long career has led me to favour is a frame placing people, not practices, centre-stage. A frame focused on people – and their emergent individual and collective needs. A frame more aligned to increased predictability, lower costs, less frustration, and more joy in work for all concerned.

A frame comprising:

- sociology

- psychology

- anthropology

- complex adaptive systems

- group dynamics

- personalised solutions

- systems thinking

- socio-technical systems approaches

Software development, as a form of collaborative knowledge work, is a predominantly social phenomenon. And as a predominantly social phenomenon we will have more success in software development when we focus on the people involved, our relationships with each other, our collective assumptions and beliefs, and everyone’s fundamental needs.

I call this the organisation’s “social dynamic”. Improve the social dynamic in a team or workplace and all the good things we’d like come for free. Like Crosby’s take on quality, we might say “success is free”.

I Invite Your Participation and Support, or At Least, Empathy

Changing the world is not for the faint hearted or indifferent. But if you give a damn, I could really use your support. And a break.

– Bob

Further Reading

Rico, D. (n.d.). Short History of Software Methods.. [online] Available at: http://davidfrico.com/rico04e.pdf [Accessed 26 Sep. 2021].

Simon Sinek (2011) If You Don’t Understand People, You Don’t Understand Business. YouTube. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8grVwcPZnuw [Accessed 29 Feb. 2020].

Quickie: Transformation Programmes

Whatever You Do Today, Don’t Start A Transformation Programme

At least, until you understand how to make it work (for which, see: Rightshifting and the Marshall Model, Organisational Psychotherapy, Memeology).

Quickie: What’s the Constraint?

What’s the biggest constraint in every organisation?

Always, always, ALWAYS, it’s management thinking*. Specifically, it’s the collective assumptions and beliefs held in common across the organisation a whole. How will you exploit this constraint?

If your approach to running your business fails to recognise this, you will fail at least 90% of the time. And the other 10% will be pure luck.

*Irrespective of whether the organisation actually has “management” or not.

First Principles

First Principles

I was reading the other day about how Elon Musk “reasons from first principles“. And I was thinking, “Well, d’oh! Doesn’t everyone do that? I know I do.” And then, upon reflection, I thought, “Hmm, maybe most folks don’t do that.” I certainly have seen little evidence of it, compare to the evidence of folks reasoning by extension, and analogy. And failing to reason at all.

Now, allowing for journalistic hyperbole and the cult of the celebrity, there may just still be something in it.

So, in case you were wondering, and to remind myself, here’s some first principles underpinning the various things in my own portfolio of ideas and experiences:

The Antimatter Principle

The Antimatter Principle emerges from the following basic principles about us as people:

- All our actions and behaviours are simply consequent on trying to get our needs met.

- We are social animals and are driven to see other folks’ needs met, often even before our own.

- We humans have an innate sense of fairness which influences our every decision and action.

Flowchain

Flowchain emerges from the following basic principles concerning work and business:

- All commercial organisations – excepting, maybe, those busy milking their cash cows – are in the business of continually bringing new products, or at least new product features and upgrades, to market.

- When Cost of Delay is non-trivial, the speed of bringing new products and feature to market is significant.

- Flow (of value – not the Mihaly Csikszentmihaly kind of flow, here) offers the most likely means to minimise concept-to-cash time.

- Autonomy, mastery and shared purpose affords a means for people to find the intrinsic motivation to improve things (like flow).

- Building improvement into the way the work works increases the likelihood of having sufficient resources available to see improvement happen.

Prod•gnosis

Prod•gnosis emerges from the following basic principles concerning business operations:

- All commercial organisations – excepting, maybe, those busy milking their cash cows – are in the business of continually bringing new products, or at least new product features and upgrades, to market.

- Most new products are cobbled together via disjointed efforts crossing multiple organisational (silo) boundaries, and consequently incurring avoidable waste, rework, confusion and delays.

- The people with domain expertise in a particular product or service area are rarely, if ever, experts in building the operational value streams necessary to develop, sell and support those products and services.

Emotioneering

Emotioneering emerges from the following basic principles concerning products and product development:

- People buy things based on how they feel (their emotional responses to the things they’re considering buying). See: Buy•ology by Martin Lindstrøm.

- Product uptake (revenues, margins, etc.) can be improved by deliberately designing and building products for maximum positive emotional responses.

- Quantification serves to explicitly identify and clarify the emotional responses we wish to see our products and service evoke (Cf. “Competitive Engineeering” ~ Gilb).

Rightshifting

Rightshifting emerges from the following basic principles concerning work in organisations:

- The effectiveness of an organisation is a direct function of its collective assumptions and beliefs.

- Effectiveness is a general attribute, spanning all aspects of an organisation’s operations (i.e. not just applicable to product development).

The Marshall Model

The Marshall Model emerges from the following basic principles concerning work in organisations:

- Different organisations demonstrable hold widely differing shared assumptions and beliefs about the world of work and how work should work – one organisation from another.

- Understanding which collection of shared assumptions and beliefs is in play in a given organisation helps interventionists select the most effective form(s) of intervention. (Cf. The Dreyfus Model of Skills Acquisition).

Organisational Psychotherapy

Organisation psychotherapy emerges from the following basic principles concerning people and organisations:

- The effectiveness (performance, productivity, revenues, profitability, success, etc.) of any organisation is a direct function of its collective assumptions and beliefs about the world of work and how work should work.

- Organisations fall short of the ideal in being (un)able to shift their collective assumptions and beliefs to better align with their objectives (both explicit and implicit).

- Having support available – either by engaging organisational therapists, or via facilitated self-help – increases the likelihood of an organisation engaging in the surfacing, reflecting upon, and ultimately changing its collective assumptions and beliefs.

– Bob

The Path to Organisational Psychotherapy

The Path to Organisational Psychotherapy

Lots of people ask me a question about Organisational Psychotherapy along the following lines:

“Bob, you’re smart, insightful, brilliant, and with decades of experience in software development. How come you’ve ended up in the tiny corner of the world which you call Organisational Psychotherapy?”

Which is a very fair question. I’d like to explain…

Background

But first a little background.

I started my lifelong involvement with software development by teaching myself programming. I used to sneak into the CS classes at school, and sit at the back writing BASIC, COBOL and FORTRAN programs on the school’s dial-up equipment, whilst the rest of the class “learned” about word processing, spreadsheets and the like. In the holidays I’d tramp across London and sneak into the computer rooms at Queen Many Collage (University) and hack my way into their mainframe to teach myself more esoteric programming languages.

My early career involved much hands-on development, programming, analysis, design, etc.. I did a lot of work writing compilers, interpreters and the like.

After a few years I found people were more interested in me sharing my knowledge of how to write software, than in writing software for them.

Flip-flopping between delivering software and delivering advice on how best to write software suited me well. I allowed me to keep close to the gemba, yet get involved with the challenges of a wide range of developers and their managers.

The years passed. I set up a few businesses of my own along the way. Selling compilers. Supporting companies’ commercial software products. Doing the independent consulting thang. Providing software development management consulting. Starting and running a software house.

By the time I got to Sun Microsystems’ UK Java Center, I had seen the software development pain points of many different organisations. From both a technical and a management perspective. Indeed, these two perspectives had come to seem indivisibly intertwingled.

I spent more and more of my time looking into the whole-system phenomena I was seeing. Embracing and applying whole-system techniques such as Theory of Constraints, Systems Thinking, Lean Thinking, Deming, Gilb, etc..

Slowly it became apparent to me that the pain points of my clients were rarely if ever caused by lack of technical competencies. And almost exclusively caused by the way people interacted. (I never saw a project fail for lack of technical skills. I often saw projects fail because people couldn’t get along.)

By the early 2000s I had arrived at the working idea that it was the collective assumptions and beliefs of my clients that were causing the interpersonal rifts and dysfunctions, and the most direct source of their pain.

So to My Answer

Returning to the headline question. It became ever clearer to me that to address my clients’ software development pains, there would have to be some (major) shift in their collective assumptions and beliefs. I coined the term “Rightshifting” and built a bunch of collateral to illustrate the idea. Out of that seed grew the Marshall Model.

And yet the key question – how to shift an organisation’s collective assumptions and beliefs – remained.

Through conversations with friends and peers (thanks to all, you know who you are) I was able to focus on that key question. My starting point: were there any known fields addressing the idea of changing assumptions and beliefs? Of course there were. Primarily the field of psychotherapy. I embraced the notion and began studying psychotherapy. A field of study to which I have continued to apply myself most diligently for more than ten years now. After a short while it seemed eminently feasible to leverage and repurpose the extensive research, and the many tools, of individual psychotherapy, to the domain of organisations and their collective assumptions and beliefs.

Summing Up

Organisational Psychotherapy provides an approach (the only approach to which I am acquainted) to culture change in organisations – and to the surfacing of and reflecting on the memes of the collective mindset – the organisational psyche. And because I see the dire need for it, I continue.

– Bob

Further Reading

Marshall, R. W. (2019). Hearts over Diamonds. Falling Blossoms.

Marshall, R. W. (2021). Memeology. Falling Blossoms.

Richard Dawkins. (1976). The Selfish Gene. Oxford University Press.

Blackmore, S. J. (2000). The Meme Machine. Oxford University Press.

The Power of Memes. (2002, March 25). Dr Susan Blackmore. https://www.susanblackmore.uk/articles/the-power-of-memes/

The Evolution Of An Idea

The Evolution Of An Idea

Many people have expressed an interest in learning more about the evolution of Organisational Psychotherapy. This post attempts to go back to the roots of the idea and follow its twists and turns as it evolved to where it is today (January 2020).

Familiar

Around the mid-nineties I had already been occupied for some years with the question of what makes for effective software development. My interest in the question was redoubled as I started my own software house (Familiar Limited) circa 1996. I felt I needed to know how to better serve our clients, and grow a successful business. It seemed like “increasing effectiveness” was the key idea.

This interest grew into the first strand of my work: Rightshifting. I had become increasingly disenchanted with the idea of coercive “process” as THE way forward. I had seen time and again how “process” had made things worse, not better. So I coined the term Rightshifting to describe the goal we had in mind (becoming more effective), rather than obsessing over the means (the word “process”, in my experience, conflating these two ideas).

“Rightshifting” describes movement “to the right” along a horizontal axis of increasing organisational effectiveness (see: chart). Even at this stage, my attention was on the organisation as a whole (and sometimes entire value chains) rather than on some specific element of an organisation, such as a software development team or department.

Circa 2008 I began to work on elaborating the Rightshifting idea, in an attempt to address a common question:

“What do all these organisations (distributed left and right along this horizontal axis) do differently, one from the other?”

Subsequently, the Marshall Model emerged (see: chart). Originally with no names for the four distinct phases, categories or zones of the model, but then over the space of a few months adding names for each zone: “Ad-hoc”, “Analytic” (as per Ackoff); “Synergistic” (as per Buckminster Fuller); and “Chaordic” (as per Dee Hock).

These names enabled me to see these zones for what they were: collective mindsets. And also to answer the above question:

Organisations are (more or less) effective because of the specific beliefs and assumptions they hold in common.

I began calling these common assumptions and beliefs a “collective mindset”, or memeplex. This led to the somewhat obvious second key question:

“If the collective mindset dictates the organisation’s effectiveness – not just in software development but in all its endeavours, across the board – how would an organisation that was seeking to become more effective go about changing its current collective mindset for something else? For something more effective?”

Organisation-wide Change

Organisation-wide change programmes and business transformations of all kinds – including so-called Digital Transformations – are renowned for their difficulty and high risk of failure. It seemed to me then (circa 2014), and still seems to me now, that “classical” approaches to change and transformation are not the way to proceed.

Hence we arrive at a different kind of approach, one borrowing from traditions and bodies of knowledge well outside conventional management and IT. I have come to call this approach “Organisational Psychotherapy” – named for its similarities with individual (and family) therapy. I often refer to this as

“Inviting the whole organisation onto the therapist’s couch“.

I invite and welcome your curiosity and questions about this brief history of the evolution of the idea of Organisational Psychotherapy.

– Bob

Further Reading

Memes Of The Four Memeplexes ~ A Think Different blog post

Beyond Command and Control – A Book Review

Beyond Command and Control – A Book Review

John Seddon of Vanguard Consulting Ltd. kindly shared an advance copy of his upcoming new book “Beyond Command and Control” with me recently. I am delighted to be able to share my impressions of the book with you, by way of this review.

I’ve known John and his work with e.g. the Vanguard Method for many years. The results his approach delivers are well known and widely lauded. But that approach is not widely taken up. I doubt whether this new book will move the needle much on that, but that’s not really the point. As he himself writes “change is a normative process”. That’s to say, folks have to go see for themselves how things really are, and experience the dysfunctions of the status quo for themselves, before becoming open to the possibilities of pursuing new ways of doing things.

Significant Improvement Demands a Shift in Thinking

The book starts out by explaining how significant improvement in services necessitates a fundamental shift in leaders’ thinking about the management of service operations. Having describe basic concepts such as command and control, and people-centred services, the book then moves on to explore the concept of the “management factory”. Here’s a flavour:

“In the management factory, initiatives are usually evaluated for being on-plan rather than actually working.”

(Where we might define “working” as “actually meeting the needs of the Folks that Matter”.)

Bottom line: the management factory is inextricable bound up with the philosophy of command and control – and it’s a primary cause of the many dysfunctions described throughout the book.

Putting Software and IT Last

One stand-out section of the book is the several chapters explaining the role of software and IT systems in the transformed service, or organisation. These chapters excoriate the software and IT industry, and in particular Agile methods, and caution against spending time and money on building or buying software and IT “solutions” before customer needs are fully understood.

“Start without IT. The first design has to be manual. Simple physical means, like pin-boards, T-cards and spreadsheets.”

If there is an existing IT system, treat it as a constraint, or turn it off. Only build or buy IT once the new service design is up and running and stable. Aside: This reflects my position on #NoSoftware.

John echoes a now-common view in the software community regarding Agile software development and the wider application of Agile principles:

“We soon came to regard this phenomenon [Agile] as possibly the most dysfunctional management fad we have ever come cross.”

I invite you to read this section for an insight into the progressive business perspective on the use of software and IT in business, and the track record of Agile in the field. You may take some issue with the description of Agile development methods as described here – as did I – but the minor discrepancies and pejorative tone pale into insignificance compared to the broader point: there’s no point automating the wrong service design, or investing in software or IT not grounded in meeting folks’ real needs.

Summary

I found Beyond Command and Control uplifting and depressing in equal measure.

Uplifting because it describes real-world experiences of the benefits of fundamentally shifting thinking from command and control to e.g. systems thinking (a.k.a. “Synergistic thinking” Cf. the Marshall Model).

And depressing because it illustrates how rare and difficult is this shift, and how far our organisations have yet to travel to become places which deliver us the joy in work that Bill Deming says we’re entitled to. Not to mention the services that we as customers desperately need but do not receive. It resonates with my work in the Marshall Model, with command-and-control being a universal characteristic of Analytic-minded organisations, and systems thinking being reserved to the Synergistic– and Chaordic-minded.

– Bob

Further Reading

I Want You To Cheat! ~ John Seddon

Freedom From Command and Control ~ John Seddon

The Whitehall Effect ~ John Seddon

Systems Thinking in the Public Sector ~ John Seddon

My Work

My Work

My work of the past ten+ years invites executives, managers and employees to ask some questions of themselves:

- What is the root of the problems in their organisation?

- What to do about it (how to fix it)?

- Why they won’t do anything about it?

The Root of the Problems

The root of the problems in your organisation is the collective assumptions and beliefs (I generally refer to these as the collective mindset) held in common by all people within the organisation. Most significant (in the conventional hierarchical organisation) are the assumptions and beliefs held in common by the senior executives. In the Marshall Model I refer to the most frequently occurring set of collective assumptions and beliefs as the Analytic Mindset.

In collaborative knowledge-work (CKW) organisations in particular, the Analytic Mindset is at the root of most, if not all, major organisational dysfunctions and “problems”.

What to Do About It

The way forward, leaving the dysfunctions of the Analytic Mindset behind, is to set about revising and replacing the prevailing set of collective assumptions and beliefs in your organisation with a new set of collective assumptions and beliefs. A collective mindset less dysfunctional re: collaborative knowledge work, one more suited to it. In the Marshall Model, I refer to this new, more effective set of collective assumptions and beliefs as the Synergistic Mindset. Yes, as an (occasionally) rational, intentional herd, we can change our common thinking, our set of collective assumptions and beliefs – if we so choose.

Why You Won’t Do Anything

You may be forgiven for thinking that changing a collective mindset is difficult, maybe impossibly so. But that’s not the reason you won’t do anything.

The real reason is that the current situation (the dysfunctional, ineffective, lame behaviours driven by the Analytic Mindset) is good enough for those in power to get their needs met. Never mind that employees are disengaged and stressed out. Never mind that customers are tearing their hair out when using your byzantine software products and screaming for better quality and service. Never mind that shareholders are seeing meagre returns on their investments. Those in charge are all right, Jack. And any suggestion of change threatens their relatively comfortable situation.

So, what are you going to do? Just ignore this post and carry on as usual, most likely.

– Bob

The Aspiration Gap

The Aspiration Gap

Some years ago I wrote a post entitled “Delivering Software is Easy“. As a postscript I included a chart illustrating where all the jobs are in the software / tech industries, compared to the organisations (and jobs) that folks would like to work in. It’s probably overdue to add a little more explanations to that chart.

Here’s the chart, repeated from that earlier post for ease of reference:

The blue curve is the standard Rightshifting curve, explained in several of my posts over the years – for example “Rightshifting in a Nutshell“.

The green curve is the topic of this post.

The Green Curve

The green curve illustrates the distribution of jobs that e.g. developers, testers, coaches, managers, etc. would like to have. In other words, jobs that are most likely to best meet their needs (different folks have different needs, of course).

Down around the horizontal zero index position (way over to the left), some folks might like to work in these (Adhoc) organisations, for the freedom (and autonomy) they offer (some Adhoc organisations can be very laissez-faire). These jobs are no so desirable, though, for the raft of dysfunctions present in Adhoc organisations generally (lack of things like structure, discipline, focus, competence, and so on).

The green curve moves to a minimum around the 1.0 index position. Jobs here are the least desirable, coinciding as they do with the maximum number of Analytic organisations (median peak of the blue curve). Very few indeed are the folks that enjoy working for these kinds of organisations, with their extrinsic (imposed) discipline, Theory-X approach to staff relations and motivations, strict management hierarchies, disconnected silos, poor sense of purpose, institutionalised violence, and all the other trappings of the Analytic mindset. Note that this is where almost all the jobs are today, though. No wonder there’s a raging epidemic of disengagement across the vast swathe of such organisations.

The green curve then begins to rise from its minimum, to reach a maximum (peak) coinciding with jobs in those organisations having a “Mature Synergistic” mindset (circa horizontal index of 2.8 to 3). These are great places to work for most folks, although due to the very limited number of such organisations (and thus jobs), few people will ever get to experience the joys of autonomy, support for mastery, strong shared common purpose, intrinsic motivation, a predominantly Theory-Y approach to staff relations, minimal hierarchy, and so on.

Finally (past horizontal index 3.0) the green curve begins to fall again, mainly because working in Chaordic organisations can be disconcerting, scary (although in a good way), and is so far from most folks’ common work experiences and mental image of a “job” that despite the attractions, it’s definitely not everyone’s cup off tea.

Summary

The (vertical) gap at any point along the horizontal axis signifies the aspiration gap: the gap between the number of jobs available (blue curve) and the level of demand for those jobs (green curve) – i.e. the kind of jobs folks aspire to.

If you’re running an organisation, where would you need it to be (on the horizontal axis) to best attract the talent you want?

– Bob

Footnote

For explanations of Adhoc, Analytic, Synergistic and Chaordic mindsets, see e.g. the Marshall Model.

The Big Shift

The Big Shift

Let’s get real for a moment. Why would ANYONE set about disrupting the fundamental beliefs and assumptions of their whole organisation just to make their software and product development more effective?

It’s not for the sake of increased profit – Deming’s First Theorem states:

“Nobody gives a hoot about profits”.

If we believe Russell Ackoff, executives’ motivation primarily stems from maximising their own personal well being a.k.a. their own quality of work life.

Is There a Connection?

Is there any connection between increased software and product development effectiveness, and increased quality of work life for executives? Between the needs of ALL the Folks That Matter and the smaller subset of those Folks That Matter that we label “executives”? Absent such a connection, it seems unrealistic (understatement!) to expect executives to diminish their own quality of work life for little or no gain (to them personally).

Note: Goldratt suggests that for the idea of effectiveness to gain traction, it’s necessary for the executives of an organisation to build a True Consensus – a jointly agreed and shared action plan for change (shift).

Is Disruption Avoidable?

So, the question becomes:

Can we see major improvements in the effectiveness (performance, cost, quality, predictability, etc.) of our organisation, without disrupting the fundamental beliefs and assumptions of our whole organisation?

My studies and experiences both suggest the answer is “No”. That collaborative knowledge work (as in software and product development) is sufficiently different from the forms of work for which (Analytic-minded) organisations have been built as to necessitate a fundamentally different set of beliefs and assumptions about how work must work (the Synergistic memeplex). If the work is to be effective, that is.

In support of this assertion I cite the widely reported failure rates in Agile adoptions (greater than 80%), Lean Manufacturing transformations (at least 90%) and in Digital Transformations (at least 95%).

I’d love to hear your viewpoint.

– Bob

Further Reading

Organisational Cognitive Dissonance ~ Think Different blog post

Digital Transformation

Digital Transformation

It seems like “Digital Transformation” of organisations is all the rage – or is it fear? – in C-suites around the world. The term implies the pursuit of new business models and, by extension, new revenue streams. I’ve been speaking recently with folks in a number of organisations attempting “Digital Transformation”, some for the fourth or fifth time. I get the impression that things are not going well, on a broad front.

What is Digital Transformation?

Even though the term is ubiquitous nowadays, what any one organisation means by the term seems to vary widely. I’ll attempt my own definition, for the sake of argument, whilst recognising that any given organisation may have in mind something rather different, or sometimes no clear idea at all. Ask ten different organisations what Digital Transformation means to them, and you’re likely to get at least ten different answers.

Digital Transformation is the creation and implementation of new business models, new organisational models and new revenue streams made possible by the use of new digital technologies and channels.

~ FlowchainSensei

Ironically it’s proving to NOT be about technology, but rather about company culture (this, in itself, being a product of the collective assumptions and beliefs of the organisation).

“A significant number of organisations are not getting [digital] transformation right because of a fundamental quandary over what digital transformation really is.”

~ Brian Solis, principal analyst and futurist at Altimeter

My Interest

So, why am I bothering to write this post? Aren’t there already reams of articles about every conceivable aspect of Digital Transformation?

Well, one aspect of Digital Transformation I see little covered is that relating to the development of “digital” products for the digitally-transformed company. And the implications this brings to the party.

Digital Transformation requires the development of new products and services to serve the new business models, new organisational models and new revenue streams. Digital products and digital services. In most cases, this means software development. And organisations, particularly untransformed organisations – which even now means most of them – are spectacularly inept at both software development and product development. Some refer to this as “a lack of digital literacy”.

Things have not changes much in this arena for the past fifty years and more. Failure rates resolutely hover around the 40% mark (and even higher for larger projects). And the much-vaunted (or is it much cargo-cullted?) Agile approach to development has hardly moved the needle at all.

For the past two decades I have been writing about the role of the collective psyche – and the impact on organisational effectiveness of the collectively-held assumptions and beliefs about how work should work. And make no mistake, effectiveness is a key issue in digital product development. Relatively ineffective organisations will fail to deliver new digital products and services at least as often as 40% of the time. Relatively effective organisations can achieve results at least an order of magnitude better than this.

The Marshall Model provides an answer to the question: what do we have to do to become more effective as an organisation? And it’s not a popular answer. By analogy, people looking to lose weight rarely like to hear they will have to eat less and exercise more. Organisations looking to become more effective rarely like to face up to the fact that they will have to completely rethink long-held and deeply-cherished beliefs about the way work should be organised, managed, directed and controlled. And remodel their organisations along entirely alien lines in order to see a successful Digital Transformation and compete effectively in the digital domain.

Successful Digital Transformations demand organisations not only come up with new business strategies, organisational models, revenue streams and digital products and services, but also that they shift their collective mindset to one which aligns with their ambitions. Personally, I see shifting the collective mindset as an essential precursor to the former. Most organisations approaching Digital Transformation fail to recognise this inevitability, this imperative. And so, most Digital Transformations are doomed to underachieve, or fail entirely.

“Ask yourself whether what you’re doing is disruptive to your business and to your industry. If you can say yes with a straight face, you may well be conducting a legitimate digital transformation.” And if you’re unable to say yes, then whatever you’re doing, it’s likely not a Digital Transformation.

If you’d like to explore this topic, understand more about the Marshall Model, its relevance and its predictive power, and save your organisation millions of Dollar/Pounds/Euros – not to mention much embarrassment and angst – I’d be delighted to chat things over with you and your executive team.

– Bob

Further Reading

Reinventing Organizations ~ Frederic Laloux

Effectiveness

Effectiveness

I recently had a bit of a wake-up call via Twitter. I asked the following question:

“What’s the one thing /above all/ that makes for an effective organisation?”

My thanks to all those who took the time to reply with their viewpoint. The wake-up call for me was the variety of these responses. All over the map might be a fair description. Which, given I’ve been writing about effectiveness in the context of organisations for more than a decade now, tells me I’ve some way to go to get my perspective across. Not that I’d expect folks to respond by simply parroting my definition, of course. And nor do I claim any special authority over the term.

Goldratt defines (in)effectiveness as:

“Things that should not have been done but nevertheless were done.”

Drucker defined it as:

“Successfully aligning behaviour with intentions.”

Aside: It’s been my experience that (organisational) effectiveness gets little attention or focus in most organisations. And seeing as how in most organisations things are so ineffective, I’ve come to believe that those making the calls don’t see a need for effectiveness.

Spectra

Effectiveness is a spectrum. From highly ineffective through to highly effective. Note that this spectrum is orthogonal to the spectrum of organisational success (by whatever measure you might choose for success: revenues, profits, social impact, personal kudos, joy, employee satisfaction, customer satisfaction, quality, returns to shareholders, executive bonuses, w.h.y.).

Effective organisations are not necessarily successful, and successful organisations are not necessarily effective. I posit that effectiveness can help create, contribute to, and sustain success. I seem to be in a minority.

Survey Results

Here’s the responses I received to my question “What’s the one thing /above all/ that makes for an effective organisation?”:

- @FragileAgile: “Folks needs being intentionally met.”

- @andycleff: “+1 to Trust. Foundation for all the things.”

- @LMaccherone: “Happy paying customers”

- @stuart_snelling: “Accurate, contextual and meaningful data that is readily accessible.”

- @ChangeTroops: ”Growth mindset.”

- @allygill: “Effective people who understand the needs of their customers (internal and external) and each other.”

- @KarimHarbott: “Totally and utterly dependent on what they are trying to achieve.”

- @ArnoutOrelio: “People”. “Their ability to improve things; their creativity.”

- @gertveenhoven: “Trust.”

- @ferigan: “A team structure that doesn’t require effort to collaborate in and allows work to flow well.”

- @anam_liath: “Common vision and ideals.”

- @rogersaner: “Empowering your people.”

- @sourabhpandey05: “I would say ‘Culture’ of the organisation. Culture which promotes1 the values trust, transparency, respect for everyone.”

- @heybenji: “Ingenuity.”

- @joserra_diaz: “Mindset of the owner.”

- @ard_kramer: “Autonomy for individuals and a common understanding of what is of value for the organisation.”

- @martinahogg: “Alignment.”

- @briscloudnative: “Love.”

- @barryfarnworth: “Understanding purpose….”

- @mikeonitstuff: “Ultimately I think it’s leadership. The leaders set the stage for the culture and the vision for the organization. Poor leadership can destroy value and morale, great leadership creates the conditions for high performance.”

- @EricStephens: “Uniform Commitment to the mission.”

For each of the above, I invite you to apply this litmus test: “if we had this, would we then necessarily be effective?”

Rightshifting

Some folks asked me for my “answer”, so here it is:

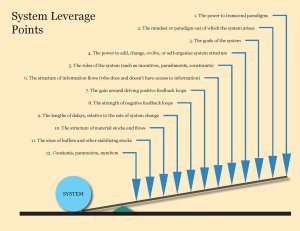

Rightshifting and the Marshall Model both attribute (relative) organisational effectiveness to the prevailing collective mindset. That’s to say, what an organisation collectively believes about how the world of work should work will absolutely dictate how effective that organisation will be. Any organisation wishing to become significantly more effective faces the formidable challenge of changing its collective assumptions and beliefs about work (in the broadest sense of the term). In other works, change the prevailing paradigm, or better yet, acquire the power to transcend /any/ particular paradigm.

For clarity then, the one thing above all that makes for an effective organisation is its collective mindset a.k.a. memeplex.

This echoes the famous “Twelve Leverage Points to Intervene in a System” by Donella Meadows:

– Bob

Solutions Demand Problems

Solutions Demand Problems

I’m obliged to Ben Simo (@QualityFrog) for a couple of recent tweets that prompted me to write this post:

I very much concur that solutions disconnected from problems have little value or utility. It’s probably overdue to remind myself of the business problems which spurred me to create the various solutions I regularly blog about.

FlowChain

Problem

Continually managing projects (portfolios of projects, really) is a pain in the ass and a costly overhead (it doesn’t contribute to the work getting done, it causes continual scheduling and bottlenecking issues around key specialists, detracts from autonomy and shared purpose, and – from a flow-of-value-to-the-customer perspective – chops up the flow into mini-silos (not good for smooth flow). Typically, projects also leave little or no time, or infrastructure, for continually improving the way the work works. And the project approach is a bit like a lead overcoat, constraining management’s options, and making it difficult to make nimble re-adjustments to priorities on-the-fly.

Solution (in a Nutshell)

FlowChain proposes a single organisational backlog, to order all proposed new features and products, along with all proposed improvement actions (improvement to the way the work works). Guided by policies set by e.g. management, people in the pool of development specialists coalesce – in small groups, and in chunks of time of just a few days – around each suitable highest-priority work item to see it through to “done”.

Prod•gnosis

Problem

Speed to market for new products is held back and undermined by the conventional piecemeal, cross-silo approach to new product development. With multiple hands-offs, inter-silo queues, rework loops, and resource contentions, the conventional approach creates excessive delays (cf cost of delay), drives up the cost-of-quality (due to the propensity for errors), and the need for continual management interventions (constant firefighting).

Solution (in a Nutshell)

Prod•gnosisproposes a holistic approach to New Product Development, seeing each product line or product family as an operational value stream (OVS), and the ongoing challenge as being the bringing of new operational value streams into existence. The Prod•gnosis approach stipulates an OVS-creating centre of excellence: a group of people with all the skills necessary to quickly and reliably creating new OVSs. Each new OVS, once created, is handed over to a dedicated OVS manager and team to run it under day-to-day BAU (Business as Usual).

Flow•gnosis

Problem

FlowChain was originally conceived as a solution for Analytic-minded organisations. In other words, an organisation with conventional functional silos, management, hierarchy, etc. In Synergistic-minded organisations, some adjustments can make FlowChain much more effective and better suited to that different kind of organisation.

Solution (in a Nutshell)

Flow•gnosis merges Prod•gnosis and FlowChain together, giving an organisation-wide, holistic solution which improves organisational effectiveness, reifies Continuous Improvement, speeds flowof new products into the market, provides an operational (value stream based) model for the whole business, and allows specialists from many functions to work together with a minimum of hand-offs, delays, mistakes and other wastes.

Rightshifting

Problem

Few organisations have a conscious idea of how relatively effective they are, and of the scope for them to become much more effective (and thus profitable, successful, etc.). Absent this awareness, there’s precious little incentive to lift one’s head up from the daily grind to imagine what could be.

Solution (in a Nutshell)

Rightshifting provides organisations with a context within which to consider their relative effectiveness, both with respect to other similar organisations, and more significantly, with respect to the organisation’s potential future self.

The Marshall Model

Problem

Few organisations have an explicit model for organisational effectiveness. Absence of such a model makes it difficult to have conversations around what actions the organisation needs to take to become more effective. And for change agents such as Consultants and Enterprise Coaches attempting to assist an organisation towards increased effectiveness, it can be difficult to choose the most effective kinds of interventions (these being contingent upon where the organisation is “at”, with regard to its set of collective assumptions and beliefs a.k.a. mindset).

Solution (in a Nutshell)

The Marshall Model provides an explanation of organisational effectiveness. The model provides a starting point for folks inside an organisation to begin discussing their own perspectives on what effectiveness means, what makes their own particular organisation effective, and what actions might be necessary to make the organisation more effective. Simultaneously, the Marshall Model (a.k.a. Dreyfus for Organisations) provides a framework for change agents to help select the kinds of interventions most likely to be successful.

Organisational Psychotherapy

Problem

Some organisations embrace the idea that the collective organisational mindset – what people, collectively believe about how organisations should work – is the prime determinant of organisational effectiveness, productivity, quality of life at work, profitability, and success. If so, how to “shift” the organisation’s mindset, its collective beliefs, assumptions and tropes, to a more healthy and effective place? Most organisations do not naturally have this skill set or capability. And it can take much time, and many costly missteps along the way, to acquire such a capability.

Solution (in a Nutshell)

Organisational Psychotherapy provides a means to accelerate the acquisition of the necessary skills and capabilities for an organisation to become competent in continually revising its collective set of assumptions and beliefs. Organisational Psychotherapists provide guidance and support to organisations in all stages of this journey.

Emotioneering

Problem

Research (cf Buy•ology ~ Martin Lindstrom) has shown conclusively that people buy things not on rational lines, but on emotional lines. Rationality, if it has a look-in at all, is reserved for post-hoc justification of buying decisions. However, most product development today is driven by rationality:

- What are the customers’ pain points?

- What are the user stories or customer journeys we need to address?

- What features should we provide to ameliorate those pain points and meet those user needs?

Upshot: mediocre products which fail to appeal to the buyers’ emotions, excepting by accident. And thus less customer appeal, and so lower margins, lower demand, lower market share, and slower growth.

Solution (in a Nutshell)

Emotioneering proposes replacing the conventional requirements engineering process (whether that be big-design-up-front or incremental/iterative design) – focusing as it does on product features – with an *engineering* process focusing on ensuring our products creaate the emotional responses we wish to evoke in our customers and markets (and more broadly, in all the Folks That Matter™).

The Antimatter Principle

Problem

How to create an environment where the relationships between people can thrive and flourish? An environment where engagement and morale is consistently through the roof? Where joy, passion and discretionary effort are palpable, ever-present and to-the-max?

Solution (in a Nutshell)

The Antimatter Principle proposes that putting the principle of “attending to folks’ needs” at front and centre of all of the organisation’s policies is by far the best way to create an environment where the relationships between people can thrive and flourish. Note: this includes policies governing the engineering disciplines of the organisation, i.e. attending to customers’ needs at least as much as to the needs of all the other Folks That Matter™.

– Bob

Some Alien Tropes

Some Alien Tropes

Most people, and hence organisations, fear the alien, And by doing so, cleave to the conventional. Yet progress, change, and organisational effectiveness depend on embracing the alien.

“Problems cannot be solved with the same mindset that created them.”

~ Albert Einstein

To help folks understand what I mean by the phrase “alien tropes” here’s a short list of tropes from the Synergistic mindset. Very alien to all the Analytic-minded organisations out there.

- Treat people like adults. In all things.

- Allow people to choose their own terms, conditions, locations, salaries, equipment and ways of working together.

- Understand who matters and what each of these individuals need.

- Attend to all the needs of all the folks that matter.

- Be aware of both the prevailing and the desired social dynamic in the organisation.

- Think in terms of communities and teams, not individuals. Ensure all the policies of the organisation support this perspective.

- Actively support and encourage self-organisation, self-management and self- determination (e.g. of teams).

- People really do want to contribute, learn, make a difference and do the best they can.

- Effective collaborative knowledge work is a learnable set of competencies.

- Skilful dialogue is essential for effective teamwork and, as a skill, requires constant practice and development.

- Intrinsic motivations add, extrinsic motivations subtract.

- Productivity in collaborative knowledge work demands superior cognitive function.

- Stress causes a decline in cognitive function.

- Stress has many causes (fear, obligation, guilt, shame, lack of safety, …).

- Eschew leadership in favour of e.g. fellowship.

- Common (shared) purpose has a unique power.

- Enthusiastically model and support discussion, debate, open-mindedness and the ability to change oneself and one’s assumptions, beliefs.

- Alien tropes do not come naturally to people. Support their uptake.

- Do not fear the alien; embrace it, use it, exploit it.

I’d be delighted to expand on any of the above, if and when invited to do so.

– Bob

Most Models Are Wrong

Most Models Are Wrong

“The most that can be expected from any model is that it can supply a useful approximation to reality: All models are wrong; some models are useful”.

~ George E. P. Box

George E. P. Box

George Edward Pelham Box FRS (18 October 1919 – 28 March 2013) was a British statistician, who worked in the areas of quality control, time-series analysis, design of experiments, and Bayesian inference. He has been called “one of the great statistical minds of the 20th century”. He repeated his aphorism concerning the wrongness of models in many of his papers.

The first appearance (1976) reads:

“Since all models are wrong the scientist cannot obtain a “correct” one by excessive elaboration. On the contrary following William of Occam he should seek an economical description of natural phenomena. Just as the ability to devise simple but evocative models is the signature of the great scientist so overelaboration and overparameterization is often the mark of mediocrity.”

~ George E. P. Box

He wrote later (1978):

Now it would be very remarkable if any system existing in the real world could be exactly represented by any simple model. However, cunningly chosen parsimonious models often do provide remarkably useful approximations. For example, the law PV = RT relating pressure P, volume V and temperature T of an “ideal” gas via a constant R is not exactly true for any real gas, but it frequently provides a useful approximation and furthermore its structure is informative since it springs from a physical view of the behavior of gas molecules.

For such a model there is no need to ask the question “Is the model true?”. If “truth” is to be the “whole truth” the answer must be “No”. The only question of interest is “Is the model illuminating and useful?”.

~ George E. P. Box

What’s A Model?

The Marshall Model belongs to the group of models collectively referred-to as Scientific Models.

“A scientific model seeks to represent empirical objects, phenomena, and physical processes in a logical and objective way. All models are in simulacra, that is, simplified reflections of reality that, despite being approximations, can be extremely useful. Building and disputing models is fundamental to the scientific enterprise. Complete and true representation may be impossible, but scientific debate often concerns which is the better model for a given task.

Attempts to formalize the principles of the empirical sciences use an interpretation to model reality, in the same way logicians axiomatize the principles of logic. The aim of these attempts is to construct a formal system that will not produce theoretical consequences that are contrary to what is found in reality. Predictions or other statements drawn from such a formal system mirror or map the real world only insofar as these scientific models are true.

For the scientist, a model is also a way in which the human thought processes can be amplified.”

“Models are typically used when it is either impossible or impractical to create experimental conditions in which we can directly measure outcomes. Direct measurement of outcomes under controlled conditions (see Scientific Method) will always be more reliable than modelled estimates of outcomes.”

The Marshall Model

I’ve written a number of blogs posts (plus a White Paper) on the Marshall Model, and its relationship with Rightshifting, so I’ll not repeat that material here.

How is the Marshall Model Useful?

- Explains the fundamental source of productivity – or lack of it – in organisations generally.

- Predicts the likely path of attempts to “go Agile or “be Agile”, embark on Digital Transformations, adopt Lean or Theory of Constraints, etc..

- Situates a range of approaches to business productivity along a spectrum (the Rightshifting spectrum), in order of effectiveness.

- Defines the challenge facing organisations that wish to significantly improve their productivity and effectiveness.

- Illustrates the role of the collective psyche (within social systems).

- Offers a way forward to higher productivity, joy, engagement and seeing folks’ needs better met.

- Provides interventionists with insights in how to intervene in organisations seeking to improve, similar to the way the Dreyfus Model provides interventionists with insights in how to intervene in situations where individuals seek to improve their skills. (How to best adapt and adopt styles of intervention to suit where the organisation is at, in its journey towards maximum effectiveness).

- Offers a seed for building a shared mental model of the factors governing an organisation’s relative effectiveness, as well as a means to understand the mental models typically in play within organisations.

Some time ago I wrote a post on how folks might use the Marshall Model.

Aside: Please let me know if you would value an elaboration of any of the above points.

Summary

“Truth … is much too complicated to allow anything but approximations.”

~ John von Neumann

The Marshall Model is not Truth. It is truthy, in that it has some utility as described above. It is a hypothesis, one I’d be delighted for folks to debate, dispute and discuss. Do you have, for example, your own go-to model for explaining organisational productivity? Where does the Marshall Model sit, for you, on the spectrum of “highly useful” through to “not very useful at all”? Would you be willing to share your viewpoint or hypothesis on organisational effectiveness and productivity?

– Bob

Further Reading

All Models are Wrong ~ Wikipedia Entry

Scientific Modelling ~ Wikipedia Entry

George E.P. Box ~ Wikipedia Entry

Mental Models ~ Wikipedia Entry

Models Are The Building Blocks of Science https://utw10426.utweb.utexas.edu/Topics/Models/Text.html

World Class? Really?

World Class? Really?

Some six years ago now, I wrote a post describing what might characterise a world class software / product development / collaborative knowledge work business.

In the interim, I’ve had some opportunities to work on these ideas for various clients. My consequent experiences, whilst in no way invalidating that post, have thrown up different perspectives on the question of “world class”.

Firstly, do you want it? Moving towards becoming a world class business involves a shed load of work, over many years. Do you want to commit to that effort? Even though the goal sounds noble, ambitious, attractive, does your business have what it takes to even begin the journey in earnest, let alone stick at it.

Then, do you need it? Absent powerful drivers spurring you on towards the goal, will you have the grit necessary to keep at it? Or will the initiative flounder and drown in the minutiae of daily exigencies, such as the constant pressure to get product and features out the door, to keep investors satisfied with (short term) results, etc.? And is the ROI there, in your context? If you do keep on the sometimes joyful, oftentimes wearisome path, and attain “world class” status, will the effort pay back in terms of e.g. the bottom line?

If your answers to the preceding two questions are yes, then we can get down to considering the characteristics of a world class collaborative knowledge-work business.

What might it look like, that goal state? Here’s my current take:

Context

Just in case a little context might help, here’s a variant of the Rightshifting chart which illustrates world class in terms of relative effectiveness (i.e. how effective are world class organisations relative to their peers?) The yellow area highlights those organisations (those at least circa 2.5 times more effective than the median) we might consider world class:

Fields of Competency

Any world class collaborative knowledge-work business must have mastered a bunch of different fields of knowledge. That’s not to say everyone in the organisation needs to have reached mastery (Level 5 – see below) in every one of the follow fields. But there must be a widespread acquaintance with all these fields, and some level of individual competent in each.

I suggest the following Dreyfus-inspired model for characterising an individual’s (practitioner’s) level of competency (or action-oriented knowledge) in any given field:

Level One (Novice)

The Novice level in each Field invites practitioners to acquire the basic vocabulary and core concepts of the Field. Attainment criteria will specify the expected vocabulary and core concepts. The Novice level also invites practitioners to acquire and demonstrate the ability to read and understand materials (books, articles, papers, videos, podcasts, etc.) related to the vocabulary and core concepts of the Field.

Level Two (Advanced Beginner)

The Advanced Beginner level in each Field invites practitioners to acquire the ability to critique key artefacts commonly found in the given Field. The Advanced Beginner level also invites practitioners to read more widely, and understand different perspectives or more nuanced aspects of, and peripheral or advanced elements within the Field.

Level Three (Competent)

The Competent level in each Field invites practitioners to acquire and demonstrate a practical competency in the core concepts in the Field, for example through the ability to apply the concepts, or create key artefacts, unaided.

The Competent level also invites practitioners to acquire and demonstrate the ability to collaborate with others in exploring and applying the abilities acquired in the Novice and Advanced Beginner levels.

Level Four (Proficient)

The Proficient level in each Field invites practitioners to acquire and demonstrate the ability to prepare and present examples and other educational materials appropriate to the given Field. The Proficient level also invites practitioners to acquire and demonstrate the ability to coach or otherwise guide others in applying the abilities acquired in the Novice, Advanced Beginner and Competent levels.

Level Five (Master)

The Master level in each Field invites practitioners to acquire and demonstrate national or international thought leadership in the Field. This can include: making significant public contributions or extensions to the Field; becoming a publicly recognised expert in the Field; publishing books, papers and/or articles relevant to the Field; etc.

The Fields

Any business that aspires to world class status must attain effective competencies in a wide range of different fields. The following list suggests the fields I have found most relevant to collaborative knowledge-work business in general, and software / product tech businesses in particular:

Flow

- Flow (product development) (n): the movement of the designs, etc., for a product or service through the steps of the design processes which create them.

- Continuous Flow (n): The progressive movement of units of design through value-adding steps within a design process such that a product design or service design proceeds from conception into production without stoppages, delays, or back flows.

- See also: Optimised Flow Demonstration (video)

Deming

- * Many in Japan credit Bill Deming for what has become known as the Japanese post-war economic miracle of 1950 to 1960.

- William Edwards Deming (October 14, 1900 – December 20, 1993) was an American engineer, statistician, professor, author, lecturer, and management consultant. Deming is best known for his work in Japan after WWII, particularly his work with the leaders of Japanese industry.

Risk Management

- Risk management is the discipline and practice of explicitly identifying and managing key risks.

“Risk Management is Project Management for grown-ups.”

~ DeMarco & Lister - Potential benefits include:

- makes aggressive risk-taking possible

- protects us from getting blindsided

- provides minimum-cost downside protection

- reveals invisible transfers of responsibility

- isolates the failure of a subproject

- Note; Many Agile practices are, at their heart, about risk management.

Mindset

- Mindset a.k.a. collective (organisational) memeplex (n): A set of memes (ideas, assumptions, beliefs, heuristics, etc.) which interact to reinforce each other.

“A memeplex is a set of memes which, while not necessarily being good survivors on their own, are good survivors in the presence of other members of the memeplex.”

~ Richard Dawkins in The God Delusion

- The “organisational mindset” is a set of beliefs about the world and the world of work which act to reinforce each other.

- These interlocking beliefs tightly bind organisations into a straight-jacket of thought patterns which many find inescapable. Without coordinated interventions at multiple points in the memeplex simultaneously, these interactions will prevail, as will the status quo.

Requirements a.k.a. Needs Management

- A more or less formal approach to identifying and communicating needs

- Any approach that ensures that everyone involved in attending to the identified needs shares a clear understanding of the required outcome(s): “doing the RIGHT thing”.

Fellowship

- A system of organisational governance based on the precepts of Situational Leadership and with a primary focus on the quality of interpersonal relationships as a means to improved organisational health and effectiveness.

- More generally, paying attend to the quality and effectiveness of the collaborative relationships across and through the business (and the extended value network of which it is a part).

Cognitive Function

- Cognitive function (Neurology) (n): Any mental process that involves symbolic operations–e.g. perception, memory, creation of imagery, and thinking; Cognitive Function encompasses awareness and capacity for judgment.

- Effectiveness of collaborative knowledge work is dictated by both e.g. quality of interpersonal relationships and degree of Cognitive Function.

- See also: Cognitive Science

PDCA

- PDCA (plan–do–check–act, or plan–do–check–adjust) is an iterative four-step method used for the control and continuous improvement of processes and products. It is also known as the Deming circle/cycle/wheel, Shewhart cycle, control circle/cycle, or plan–do–study–act (PDSA).

- Based on the scientific method, (Cf. Francis Bacon) e.g. “hypothesis” – “experiment” – “evaluation”.

Statistical Process Control (SPC)

- Statistical process control (SPC) is a method of quality control which uses statistical methods. SPC is applied in order to monitor and control a process.

- Key tools used in SPC include control charts; a focus on continuous improvement; and the design of experiments.

- See also: The Red Beads and the Red Bead Experiment with Dr. W. Edwards Deming (video)

Lean Product Development

- Lean Product Development applies ideas from Lean Manufacturing to the design and development of new products (See e.g. books by Allen Ward and Michael Kennedy)

- Aims to improve the flow of new ideas “from concept to cash”.

- Can also help raise levels of innovation.

- Exemplar: TPDS (Toyota Product Development System)

Don Reinertsen’s Work

- Don Reinertsen is the author of three of the most definitive and best-selling books on product development.

- His 1991 book, Developing Products in Half the Time is a product development classic.

- His 1997 book, Managing the Design Factory: A Product Developer’s Toolkit, was the first book to describe how the principles of Just-in-Time manufacturing could be applied to product development. In the past 16 years this approach has become known as Lean Product Development.

- His latest award-winning book, The Principles of Product Development Flow: Second Generation Lean Product Development, has been praised as, “… quite simply the most advanced product development book you can buy.”

Neuroscience

- (Cognitive) neuroscience is concerned with the scientific study of the biological processes and aspects that underlie cognition, with a specific focus on the neural connections in the brain which are involved in mental processes.

- (Cognitive) neuroscience addresses the questions of how psychological/cognitive activities are affected or controlled by neural circuits in the brain. Cognitive neuroscience is a branch of both psychology and neuroscience, overlapping with disciplines such as physiological psychology, cognitive psychology, and neuropsychology.

- See also: Cognitive Function

Theory of Constraints

- The Theory of Constraints (TOC) is a management paradigm originated by Eliyahu M. Goldratt.

- TOC proposes a scientific approach to improvement. It hypothesises that every complex system, including manufacturing processes, consists of multiple linked activities, just one of which acts as a constraint upon the entire system (the “weakest link in the chain”).

- TOC has a wide range of “thinking tools” which together form a coherent problem-solving and change management system.

Self-organisation

- Self-organisation (n): Ability of a system to spontaneously arrange its components or elements in a purposeful (non-random) manner. It is as if the system knows how to ‘do its own thing.’ Many natural systems such as cells, chemical compounds, galaxies, organisms and planets show this property. Animal and human communities too display self-organization.

“An empowered organization is one in which individuals have the knowledge, skill, desire, and opportunity to personally succeed in a way that leads to collective organisational success.”

~ Stephen R. Covey

Quantification

- In mathematics and empirical science, quantification is the act of counting and measuring that maps human sense observations and experiences into members of some set of numbers. Quantification in this sense is fundamental to the scientific method.

- See also: Tom Gilb

Systems Thinking

- Systems thinking provides a model of decision-making that helps organisations effectively deal with change and adapt.

- It is a component of a learning organisation – one that facilitates learning throughout the organisation to transform itself and adapt.

- See also: Peter Senge, Russell L. Ackoff, Donella Meadows, etc.

Psychology

- Psychology (n): the study of behaviour and mind, embracing all aspects of conscious and unconscious experience as well as thought. It is an academic discipline and an applied science which seeks to understand individuals and groups.

Argyris

- An American business theorist, Professor Emeritus at Harvard Business School, and known for his work on interpersonal communication, organisational effectiveness, double-loop learning and learning organisations.

- See also: Action Science.

Psychotherapy

- Psychotherapy (n): interventions which facilitate the shifting of perspectives and attitudes, and thus, human behaviours.

- See also: Organisational Psychotherapy

To the above list of Fields, I invite you to add any which may have specific resonance or relevance to your own business.

And then there are the lists of technical capabilities you need to be present in your various business functions, too.

Aside – CMMI

As an aside, CMMI also provides an extensive list of “capability areas” ( circa 128 different areas, last time I looked) focussed on engineering capabilities. Note: I find the CMMI list useful, but only as a primer, not as a full-blown recipe for success.

Summary

All the above begs the question: how to get there? And, how close are you to world class, so far?

– Bob