The Rightshifting Ethos

[From the Archive: Originally posted at Amplify.com Mar 20, 2011]

I tweeted this morning:

“Say what you believe – and see who follows” ~ Seth Godin | +1

followed by:

“I believe that a Rightshift of knowledge-work businesses will bring improved health, wealth and wisdom for [both] individuals and society at large”

Given the chord I know this strikes with some folks, I thought I’d explain this belief in just a little more detail…

Health

Many researchers have written of the correlation between meaningless work, lack of job satisfaction, etc and personal health issues brought on by e.g. stress. Marcus Buckingham in First Break All the Rules summarises 25 years of Gallup research into what makes for a satisfying job. And recent research points to the deleterious effects of job-related stress on individuals’ health and well-being.

So, I believe that an improvement in job satisfaction brings about a reduction in job-related health issues. Happier people are indeed healthier people. And given the long hours almost all of us spend working, a happier work experience can contribute markedly to a happier life.

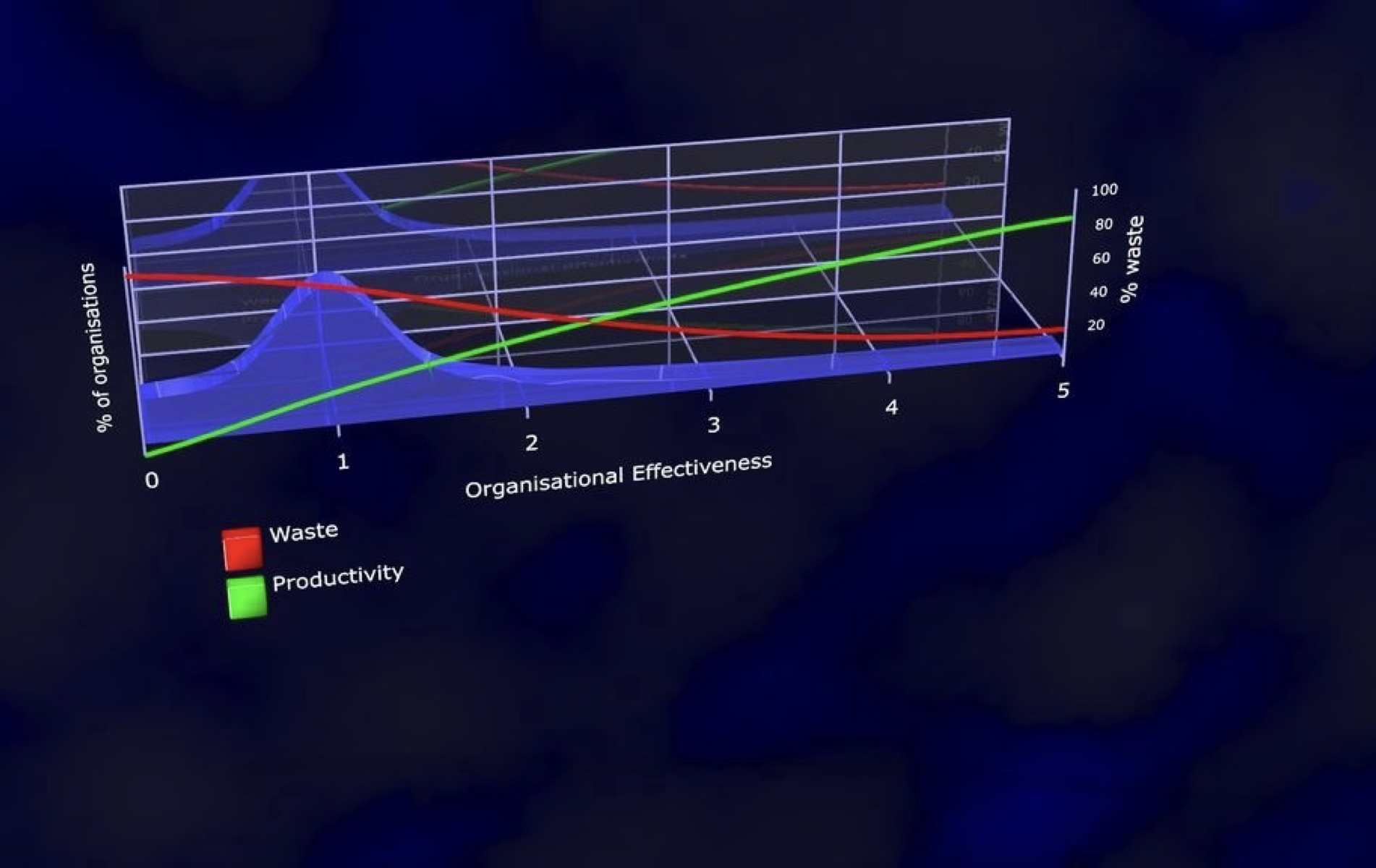

Rightshifting an organisation means “making it more effective at achieving its intent, or business objectives” (see chart):

(For the purposes of this post, we can use the green productivity line as a proxy for job satisfaction).

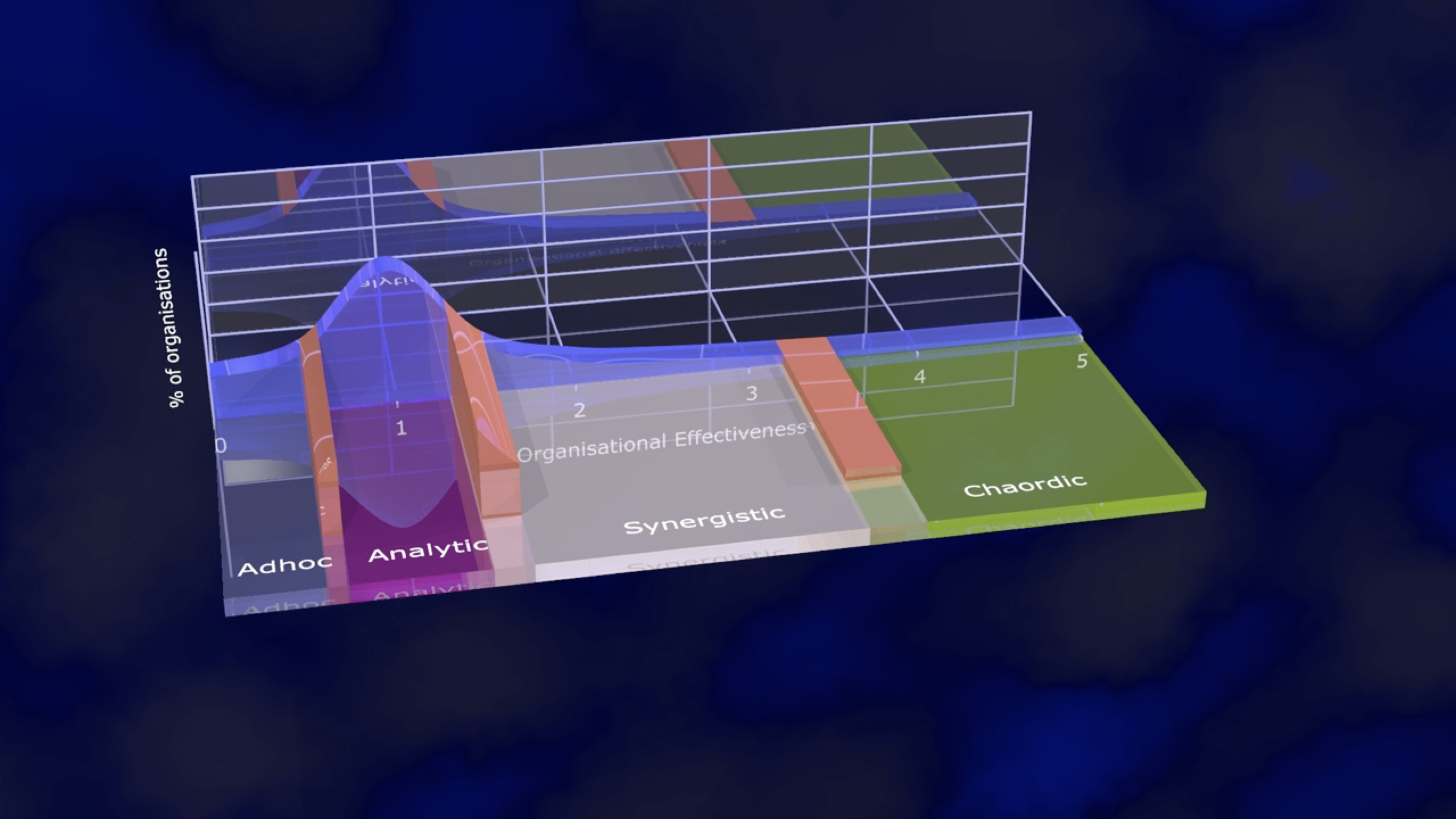

In practice, significant improvements in organisational effectiveness can only come about through the organisation transitioning to a different mindset. The Marshall Model explains this in more detail (see the Marshall Model White Paper, and diagram, below):

I don’t think it’s any coincidence that as we move to the right on this diagram, we find organisations where job satisfaction is much higher than in those organisations to the left. So, Rightshifting any given organisation means that folks in that organisation will find greater job satisfaction, engagement, etc. And this means, I believe, that they will also have less (negative) stress and therefore improved health. And if people are less stressed and happier at work, I also believe that will contribute, indirectly, to a more healthy society for all of us.

Wealth

As organisations shift to the right (become more effective), that implicitly means that they will be more successful commercially. Margins should improve, as should revenue and market share. Couple this with a more enlightened and “fairer” attitude towards sharing success with all stakeholder (including employees), and I believe that those who work in rightshifted organisations will benefit by earning more than their counterparts in those organisations to the left. And as organisations earn more, and move to a perspective of e.g. greater corporate social responsibility, I believe the commercial successes of these organisations will trickle-down directly and indirectly into the greater prosperity of their host societies.

Wisdom

Organisations have been locked, seemingly irrevocably, in the Taylorist, Theory-X, command-and-control approach to management for more than a century now. Rightshifted organisations have learned that this perspective on the management of organisations (specifically, of knowledge-work organisations) has outlived its usefulness, and other, more effective, and moreover, more humane means to managing work now exist. This seems like wisdom to me.

Conclusion

This is what I believe. If you believe in the same interpretation of cause and effect, and share my hope for a better, more humane world of work, civil society, and world in general, I invite you to join with us in the Rightshifting movement. Thank you for reading.

– Bob