Breadcrumbz

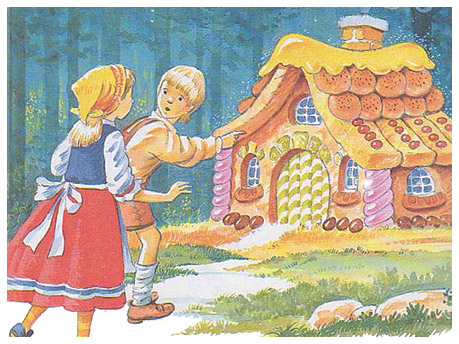

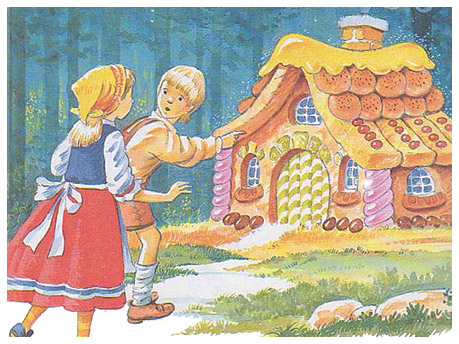

In the popular fairy tale recorded by the Brothers Grimm, two children, Hansel and Gretel, leave a trail of breadcrumbs behind them as they are led deep into the dark and forbidding woods to die. Nothwithstanding the plot twist in which their breadcrumbs are eaten by birds, more recently the term “breadcrumbs” has come to mean any series of links or steps which allow people to keep track of their location, by means of references to the way back “home”.

I often feel the whole tech industry is like a bunch of children lost in the dark and forbidding wood, lacking a trail of breadcrumbs, not knowing which way to turn to find their way out and back “home” – home where software and product development is warm, safe, secure, and successful.

With the Antimatter Principle, I see a path out of the darkness, and a way back home. A path of breadcrumbs (without those pesky birds).

The Idealised Design

If we had a blank slate, what kind of situation might we choose to create, in order to build organisations that are highly effective at knowledge work – and meeting customers’ needs?

Research in various fields such as psychology, neuroscience and sociology have provided us with breadcrumbs along the path to that “home”. Here are some of the breadcrumbs I have in mind:

Low Distress

Distress reduces cognitive function. That’s to say, when we’re stressed-out, we simply can’t think any where near as well as when we’re more calm and unworried. Distress also contributes to ill-health (both physical and mental) and even increased mortality rates (death).

High Eustress

Eustress (positive stress) gives us positive motivation, derived from feelings of fulfilment, increased attention and higher levels of interest in what we’re doing. Eustress correlates with challenging work (depending on our perception of that work). Stress in the workplace is unlikely to go away any time soon, but we can adjust our perceptions such that we derive more eustress and less distress from the inevitable stressful stimuli.

Immersion

When we’re immersed, zoned-in, fully present in doing something, we derive feelings of energized focus, full involvement, and enjoyment. In other words, most people love the feeling of being completely absorbed in what they’re doing. The psychologist Mihály Csíkszentmihályi goes so far as to describe this state as one of “spontaneous joy, even rapture, while performing a task.”

Autonomy

“We must completely abandon the goal of getting other people to do what we want.”

~ Marshall B. Rosenberg

Coercion and use of force tends to generate hostility and to reinforce resistance to the very behaviours we are seeking. Genuine autonomy – lack of all coercion – is so far from how most people see the world, it may be the most difficult breadcrumb of them all for us to embrace.

Absence of Fear

Fear (of e.g. punishment) diminishes our self-esteem and our goodwill towards the perpetrators. It also obscures any compassion underlying the perpetrators demands. We’d all like folks to take action out of the desire to contribute to life – rather than out of fear, guilt, shame, or obligation. Wouldn’t we?

A Multitude of Opportunities for Gratitude

Research in the fields of neuroscience and positive psychology show us that the expression of gratitude can have profound and positive effects – for example, making us happier, healthier and more positively-disposed towards others (pro-social motivation).

“A growing body of research shows that gratitude is truly amazing in its physical and psychosocial benefits.”

~ Dr. Blair Justice & Dr. Rita Justice

Empathy

“Our goal is to create a quality of empathic connection that allows everyone’s needs to be met.”

~ Marshall B. Rosenberg

By empathy, I’m choosing to use the term as it’s often used in e.g. counselling: an expression of the regard and respect we hold for another – whose experiences maybe quite different from our own.

“I have a sense of your world, you are not alone, we will go through this together”.

Carl Rogers, the founder of person-centred counselling, concluded that the important elements of empathy are:

- We understand the other person’s feelings.

- Our responses reflect the other person’s mood, and the content of what has been said.

- Our tone of voice conveys the ability to share the other person’s feelings.

“It’s harder to empathise with those who appear to possess more power, status, or resources than us.”

Presence

By presence I mean simply taking the time and effort to be present with one another, giving fully of our attention, with deep respect and genuine interest.

“Our presence is the most precious gift we can give to another human being.”

I share the view of Nancy Kline, author of “More Time to Think” and proponent of the idea of the “Thinking Environment”, that

“The quality of our attention determines the quality of other people’s thinking.”

~ Nancy Kline

Beauty

We may choose to see the inherent beauty in being human, and thereby the beauty in our needs – needs related to our essential nature as human beings.

We are by nature compassionate. We are by nature alive. We are by nature creative.

We are by nature playful. All of these qualities manifest us as human beings.

And when we act as fully human, this beauty emanates, and we live it and we see it in other people, and in the wider world of Nature, too.

Joy

“I believe that the most joyful and intrinsic motivation human beings have for taking any action is the desire to meet our needs and the needs of others.”

~ Marshall B. Rosenberg

Isn’t joy the motivation we’d most wish folks to act out of? So much better than fear, obligation, guilt or shame. And so much more effective than e.g. money, fame, power-over or other such extrinsic motivations.

Feelings

Most workplaces I have come across have been toxic to the expression of feelings and emotions. “Business” and emotions are not cozy bed-fellows, it would seem. Yet the irony is that all business is, at its root, driven by emotion. Everything we do as human beings is driven by emotion (and concomitant needs). People buy because of emotion. People make decisions and choices based on emotion. Even “hard” science is largely moderated by emotion.

Repressing our emotions causes us distress, and denies our humanity.

Mutuality

We can’t win at somebody else’s expense. We can only fully be satisfied when other folks’ needs are fulfilled as well as our own. This is not the common theory-in-use in capitalism.

Spirituality

“Unless we come from a certain kind of spirituality, we’re likely to create more harm than good.”

Summary

Constructing our idealised design, by following the path laid out by these breadcrumbs, we may just find ourselves living and working in organisations that better meet our needs as human beings, and that (better) meet the needs of ALL the folks – owners, shareholders, core groups, executives, managers, employees, customers and society at large – whom our organisations ostensibly exist to serve.

– Bob