Reliability and Effectiveness

Reliability and Effectiveness

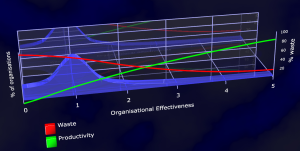

Many times when presenting either the Rightshifting curve:

or the Marshall Model:

I have been asked to define “Effectiveness” (i.e. the horizontal axis for both of these charts). I have never been entirely happy with my various answers. But I have recently discovered a definition for effectiveness, including a means to measure it, which I shall be using from now on. This definition is by Goldratt, as part of Theory of Constraints, and appears in his audiobook “Beyond the Goal”.

Measurements

Measurements serve us in two ways:

- As indicators of where we are, so we know where to go. For example, the dials and gauges on a car’s dashboard.

- As means to induce positive behaviours.

We must always remember, though, that we are dealing with humans and human-based organisations:

“Tell me how you measure me and I’ll tell you how I behave.” ~ Goldratt

We must choose measurements to induce the parts to do what’s better for the company as a whole. If a measurement jeopardises the performance of the system as a whole, the measurement is wrong.

Companies already have one set of measurements which measure their performance as a whole: their Financial measurements: e.g. Net profit (P&L) and investment (Balance Sheet)

What about when we dive inside the company as a whole, though? We then have two areas in which we have to conduct measurements:

- Support for and evaluation of management decisions

- Oversight on execution (how well are we executing on the decisions we’ve made?)

We generally don’t have good measurements in terms of decisions, nor good measurements in terms of execution.

We have to remember we’re dealing with human beings. And as long as we’re dealing with human beings, we have to realise that by judging any person on more than five measure, we’re creating anarchy. Simply because, with more than five measurements, people can basically do whatever they like, and likely still score high on one of them. And their bosses can nail them on some measurement they fail to deliver against. More than five measurements is conceptually wrong.

Categories of Measurement

So, how to categorise thing so that human beings can grasp the situation? Can we do better than we do now? Theory of Constraints suggests we can.

What resources do we have to help us formulate measurements in each of the above two areas; management decision-making, and execution of those decisions?

- For decision-related measurements – there are lots of resources available to help e.g. books on Throughput Accounting.

- For execution-related measurements – there is next to nothing published anywhere.

Continuous Improvement

I’ll not make the case for continuous improvement here. But if we wish to induce people to continuously improve, where should we focus our measurements? On things that are done properly, or on things that are not done properly? Which of these two foci better drives action? Focussing on the things we’re doing properly tends not to drive improvement. So we must concentrate on things that are not done properly.

How many things are not done properly? Kaplan suggests that in most businesses, there are more than twenty categories of things that are not done properly. But for humans to grasp our measures, we have already decided we need at most five categories, categories that completely cover everything that is not done properly, with zero overlap or duplication. Finding a way to categorise things that meets our criteria here is a nontrivial challenge.

Goldratt says there are only two categories:

- Things that should have been done but were not.

- Things that should not have been done but nevertheless were done.

Just two categories, with zero overlap. Beautifully simple.

And each of the above two categories already have a word defining them:

- Things that should have been done but were not – unreliability.

- Things that should not have been done but nevertheless were done – ineffectiveness.

Let’s swap these around into positive terms: Reliability, and Effectiveness.

Lovely.

Reliability and Effectiveness

Can we find measures to quantify Reliability and Effectiveness? How can we put numbers on our reliability? How can we put numbers on our effectiveness? Because, without numbers, we’re not measuring.

Let’s consider what is the end result of being reliable, in terms of the system as a whole. And what is the end result of being effective, in terms of the system as a whole? Not in financial terms though, as reliability and effectiveness are not financial things. We know this intuitively.

Reliability

Things that should have been done but were not.

The end result of being unreliable, in terms of the system as a whole, is that the company fails to fulfil its commitments to the external world. In other words, the company fails to ship on time. Do we already measure on-time shipment? Yes. We call it Due Date Performance. That’s a measure of how much we ship on time. “Our company Due Date Performance is 90%”. The unit of measure is almost always “percent”. What behaviour does this unit of measure trigger? Does it trigger behaviour that is good for the company? No. It encourages us to sacrifice on-time shipment of difficult, larger shipments in favour of smaller, easier shipments. So the dollar value of the sale must be part of any reliability measurement. We cannot ignore the dollar value. And neither is time is a factor in percent units. How late is each late shipment? We must include time, too. So, let’s change our “Reliability” units from “percent” to “Throughput dollar days” – the sales dollar value of each orders that is late, multiplied by the number of days it is late, summed across all late orders. The sum total is the measurement of our (un)reliability.

This is of course a new unit of measure: Throughput-dollar-days. To infer trends, or to compare the performance of e.g. groups or companies, we will need time to train our intuition in the significance of this new unit of measure. As we begin to get to grips with this new unit of measure, it can help to present it as an indicator (a number in some fixed range, say 1-10, or as we use in Rightshifting, and the Marshall Model, 0-5) until we have adjusted to the Throughput-dollar-days measure.

Effectiveness

Things that should not have been done but nevertheless were done.

If we do things that we should NOT have been doing, what is the end result? Inventory. Do we already measure inventory? Of course we do. But how do we presently measure inventory? Either in terms of a dollar value, for example “$6 million of finished good inventory”, or in terms of a number of days, for example “60 days of finished goods inventory”. But both dollars AND time are important. Existing units of measurement for inventory drive unhelpful local behaviours like over-production and poor flow. So, how to measure to induce helpful behaviours? For each item of inventory, let’s use the dollar value of the inventory multiplied by the number of days that we’re holding that inventory under our local authority. We’ll call this unit of measure “Inventory-dollar-days”.

And one more measure of effectiveness: local operating expense. (For example, scrap, or salaries – with a given subunit of the company).

Note: We can fold quality into these measures simply by not recognising a sale, or a reduction in inventory, until the customer accepts the items (i.e. until the items meet the customer’s quality standards).

Summary

Now we have means for defining effectiveness, (and reliability) in a way in which we can also measure it. I feel very comfortable with that.

– Bob

Further Reading

Beyond the Goal ~ Eliyahu M. Goldratt (Audiobook only)

Relevance Lost: Rise and Fall of Management Accounting ~ Kaplan & Johnson

The Goal ~ Eliyahu M. Goldratt

Throughput Accounting ~ Thomas Corbett

The Balanced Scorecard: Translating Strategy into Action ~ Kaplan & Norton

This was great – I’ve been swinging back through Goldratt’s work due to client needs and this was perfect timing.