Local Optima – Updated

[First posted as Local Optima on July 21, 2014]

I’ve heard that a picture is worth a thousand words. And more recently, some research has shown that information presented visually has more likelihood of convincing.

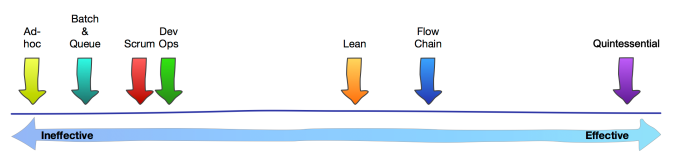

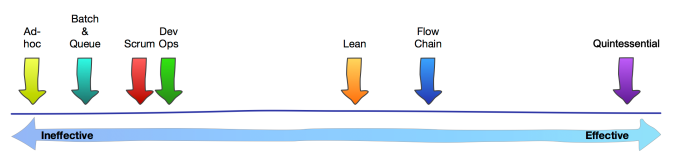

So, here’s a chart. It illustrates the relative effectiveness of the different approaches to e.g. developing software products and systems. The X-axis is the relative effectiveness, increasing towards the right. This same axis also maps from a narrow, local focus on parts of a system (left-hand side) to a broad, global focus on the interactions between the parts of a system (right-hand side).

Note: This chart represents aggregates – any given development effort may show some deviation from this aggregate. And also note, we’re talking about effectiveness from the broader perspective: meeting customer needs, whilst also satisfying the developers and other technical staff, managers, executives, sales folks, suppliers, etc. – i.e. all Folks That Matter™️. I also assume the aggregates exclude LAME, Wagile and other such faux approaches where folks claim to be working in certain ways, but fail to live up to those claims.

What Is a Local Optimum?

This post is primarily about the pernicious and dysfunctional effects of using approaches predicated on local optima. By which I mean, taking a narrow view of (part of) a “system of problems” aka mess. Or, in other words, respecting the boundaries of functional silos within an organisation.

Many folks seem to believe that improving one part of the whole organisation – e.g. the software development function, or an individual team – will improve the effectiveness of the whole organisation. As Ackoff shows us, this is a fallacy of the first order: it’s the interactions between the parts of the organisation-as-a-whole that dictate the whole-system performance. In fact, improving any one part in isolation will necessarily detract from the performance of the whole.

This performance-of-the-whole is most often the kind of performance that senior executives and customers (those who who express a preference) seem to care about – very much in contrast to the cares of those tasked with, and incentivised for, improving the performance of a given part (e.g. team, group, department or function).

“When a mess, which is a system of problems, is taken apart, it loses its essential properties and so does each of its parts. The behavior of a mess depends more on how the treatment of its parts interact than how they act independently of each other. A partial solution to a whole system of problems is better than whole solutions of each of its parts taken separately.”

~ Russell. L. Ackoff

Ad-hoc

Also known as code-and-fix, hacking, messing about, and so on. Coders just take a run at a problem, and see what happens. Other skills and activities, such as understanding requirements, architecture, design, UX, testing, transfer into production, etc., if they do happen, happen very informally.

Batch & Queue

Perhaps more widely known as “Waterfall”. In this approach a big batch of work – often a complete set of requirements – passes through various queues, eventually ending up as working software (hopefully), or as software integral to a broader product or service.

Scrum

One of the various flavours of agile development. Other dev-team centric approaches (xp, kanban, scrumban, FDD, etc.) have similar relative effectiveness, whether combined or “pure”.

DevOps

DevOps here refers to the integration of dev teams with ops (operations/production) teams. This joining-up of two traditionally distinct and separate mini-siloes within the larger IT silo gives us a glimpse of the (slight) advantages to effectiveness resulting from taking a slightly bigger-picture view. Bigger than just the dev team, at least.

Lean

Lean Software Development aka Lean Product Development. The (right)shift in effectiveness comes from again taking an even broader view of the work. Broader not only in terms of those involved (from the folks having the original ideas through to the folks using the resulting software /product) but also broader over time. Approaches like TPDS – including SBCE – improve flow and significantly reduce waste by accepting that work happens more or less continuously, over a long period of time, not just in short, isolated things called “projects” nor for one-off things called “products”.

FlowChain

(Including e.g. Prod•gnosis and Flow•gnosis.) My own thought-experiment at what a truly broad, system-wide perspective on software and product development could make possible in terms of improved effectiveness.

Quintessential

The best conceivable approach in the real world. I’ve included this (as an update from my 2014 post, therein named “Acme”) as a milestone for just how far we as an industry have yet to go in embracing the advantages of a broad, interaction-of-the-parts perspective, as opposed to our current, widespread obsession with narrow improvements of individual parts of our organisations. NB My recent book “Quintessence” sets out a map or blueprint of this Quintessential organisation, as well as the means to get there (i.e. Organisational Psychotherapy).

Please do let me know if you’d like me to elaborate any further on any of the above descriptions.

– Bob

Postscript

For some reason which made sense inside my head at the time, I omitted Theory of Constraints from the above chart. For the curious, I’d place it somewhere between Lean and FlowChain.