Antimatter Evo

Tom Gilb has long been known for his “Evo”(evolutionary) approach to software engineering, and more recently for his sharp criticisms of the Agile Manifesto (99% of which I agree with).

In a recent (February 2018) PPI Systems Engineering Newsletter, he authors the feature article “How Well Does the Agile Manifesto Align with Principles that Lead to Success in Product Development?”, describing in some depth his issues with the Agile Manifesto, its Four Values and Twelve Principles.

Apropos the latter, Tom comments at length on each, providing for each a “reformulation”. I repeat each of these twelve reformulations here, along with a translation to the vocabulary (and frame) of the Antimatter Principle:

1. Our highest priority is to satisfy the customer through early and continuous delivery of valuable software.

Tom’s reformulation: Development efforts should attempt to deliver, measurably and cost-effectively, a well-defined set of prioritized stakeholder value-levels, as early as possible.

Antimatter translation: As early and frequently as possible, in the course of developing e.g. a new product or service, we (the development team) will identify, quantify, and subsequently measure, a well-defined set of the needs of all the people that matter, and deliver, as early and frequently as possible, stuff that we believe meets those needs.

Antimatter simplification: Our highest priority is to continually attend to the needs of everyone that matters.

2. Welcome changing requirements, even late in development. Agile processes harness change for the customer’s competitive advantage.

Tom’s reformulation: Development processes must be able to discover and incorporate changes in stakeholder requirements, as soon as possible, and to understand their priority, their consequences to other stakeholders, to system architecture plans, to project plans, and contracts.

Antimatter translation: Our approach to developing new products or services enables the development team to discover and incorporate changes in the needs of anyone that matters, and the members of the community of “everyone that matters”, as soon as possible. The development team has means to quantify, share and compare priorities, and means to both understand and communicate the impact of such changes to the community of “everyone that matters”.

Antimatter simplification: Handle changing needs, and changing membership of the “everyone that matters” community, in ways that meet the needs of the people that matter.

3. Deliver working software frequently, from a couple of weeks to a couple of months, with a preference to the shorter timescale.

Tom’s reformulation: Plan to deliver some measurable degree of improvement, to planned and prioritized stakeholder value requirements, as soon, and as frequently, as resources permit.

Antimatter translation: Plan to deliver some measurable degree of improvement to the planned and prioritised set of needs (of the people that matter) as soon, and as frequently, as needed.

Antimatter simplification: Deliver stuff as often as, and by means that, meets the needs of everyone that matters.

4. Business people and developers must work together daily throughout the project

Tom’s reformulation: All parties to a development effort (stakeholders), need to have a relevant voice for their interests (requirements), and an insight into the parts of the effort that they will potentially impact, or which can impact them, on a continuous basis, including into operations and decommissioning of a system.

Antimatter translation: Have established means through which we continually solicits the needs of the people that matter, means that are well-defined and well-understood by everyone that matters. These means provide: an ear for the feelings and needs of the people that matter, and feedback on the consequences (impact) of attending to those needs.

Antimatter simplification: Share needs and solutions as often as, and by means that, meets the needs of everyone that matters.

5. Build projects around motivated individuals. Give them the environment and support they need, and trust them to get the job done.

Tom’s reformulation: Motivate stakeholders and developers, by agreeing on their high-level priority objectives, and give them freedom to find the most cost-effective solutions.

Antimatter translation: Motivate everyone that matters by agreeing on everyone’s needs, and give everyone, as a group, the freedom to collaborate in negotiating the trade-offs, priorities, and most cost-effective solutions.

Antimatter simplification: Motivate people to the degree that, and by means that, meets the needs of everyone that matters.

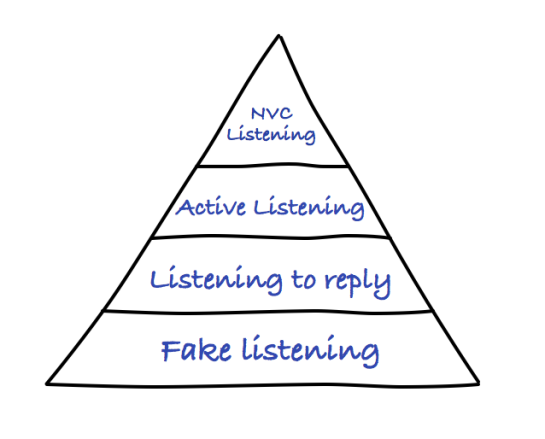

6. Enable face-to-face interactions.

Tom’s reformulation: Enable clear communication, in writing, in a common project database. Enable collection and prioritization, and continuous updates, of all considerations about requirements, designs, economics, constraints, risks, issues, dependencies, and prioritization.

Antimatter translation: Provide communications that meet the needs of everyone that matters. Manage these needs, including negotiated solutions, just as all the other needs in the endeavour.

Antimatter simplification: Facilitate sharing of information, feelings, needs, etc. to the degree that, and by means that, meets the needs of everyone that matters.

7. Working software is the primary measure of progress.

Tom’s reformulation: The primary measure of development progress is the ‘degree of actual stakeholder-delivered planned value levels’ with respect to planned resources, such as budgets and deadlines.

Antimatter translation: The primary measure of development progress is the ‘degree of actual needs met’ with respect to the planned, prioritised and quantified set of needs of everyone the matters. Note: Assuming end-users or customers are amongst the set of people that matter, this demands the product or service in question is in active service with those people, such that we can measure how well (the degree to which) their needs are actually being met. And don’t forget the needs pertaining to how the endeavour is being conducted!

Antimatter simplification: Choose a primary measure of progress that meets the needs of everyone that matters.

8. Agile processes promote sustainable development. The sponsors, developers, and users should be able to maintain a constant pace indefinitely.

Tom’s reformulation: We believe that a wide variety of strategies, adapted to current local cultures, can be used to maintain a reasonable workload for developers, and other stakeholders; so that stress and pressures, which result in failed systems, need not occur.

Antimatter translation: Proceed at a pace that meets the needs of everyone that matters. Manage these (dynamic and potentially conflicting) needs, including negotiated solutions, just as all the other needs in the endeavour.

Antimatter simplification: Choose a pace that meets the needs of everyone that matters.

9. Continuous attention to technical excellence and good design enhances agility.

Tom’s reformulation: Technical excellence in products, services, systems and organizations, can and should be quantified, for any serious discussion or application. The suggested strategies or architectures, for reaching these ‘quantified excellence requirements’, should be estimated, using Value Decision Tables [45, 1, 2], and then measured in early small incremental delivery steps.

Antimatter translation: Aim for a level of technical excellence and good design – and any other quality-related attributes – that meet the needs of everyone that matters. Manage these (dynamic and potentially conflicting) needs, including negotiated solutions, just as all the other needs in the endeavour.

Antimatter simplification: Agree on attributes of quality, and levels of quality, with respect to the means of the endeavour, that meets the needs of everyone that matters.

10. Simplicity – the art of maximizing the amount of work not done – is essential.

Tom’s reformulation: We need to learn and apply methods, of which there are many available, to help us understand complex systems and complex relations. [1, 2, 46, 47, 48, 49] and succeed in meeting our goals in spite of them.

Antimatter translation: Aim for a level of simplicity – and any other quality-related attributes -that meet the needs of everyone that matters. Manage these (dynamic and potentially conflicting) needs, including negotiated solutions, just as all the other needs in the endeavour.

Antimatter simplification: Spend effort only where it directly attends to some need of someone that matters.

11. The best architectures, requirements, and designs emerge from self-organizing teams.

Tom’s reformulation (A): The most useful value and quality requirements will be quantified, and will use other mechanisms, including careful corresponding stakeholder analysis [1, 51, and 52], to facilitate understanding.

Tom’s reformulation (B): The most cost-effective designs/architecture, with respect to our quantified value and resource requirements, will be estimated and progress tracked, utilizing a Value Decision Table with its evidence, sources, and uncertainty. They will be prioritized by values/resources with respect to risks [45].

Tom’s reformulation (Simplified, combined): We will use engineering quantification for all variable requirements, and for all architecture.

Antimatter translation: Choose organisational structures and methods (teams, heroes, feature teams, self-organisation, quantification, etc.) for the endeavour that meet the needs of everyone that matters. Manage these (dynamic and potentially conflicting) needs, including negotiated solutions, just as all the other needs in the endeavour.

Antimatter simplification: Agree on attributes of quality, and levels of quality, with respect to the organisation of the endeavour, that meets the needs of everyone that matters.

12. At regular intervals, the team reflects on how to become more effective, then tunes and adjusts its behavior accordingly.

Tom’s reformulation: A process like the Defect Prevention Process (DPP), or another more-suitable for current culture, which delegates power to analyze and cure organizational weaknesses, will be applied: using participation from small self-organized teams to define and prove more cost-effective work environments, tools, methods, and processes.

Antimatter translation: Aim to learn as much from our work as meets the needs of everyone that matters. Manage these needs, including negotiated solutions, just as all the other needs in the endeavour.

Antimatter simplification: Pursue improvement, with respect to the means and organisation of the endeavour, that meets the needs of everyone that matters.

Summary

The key insight that emerges from this exercise in translation is this:

Once we have a more-or-less formal and established approach for identifying who matters and their needs, with respect to the endeavour at hand – and then tracking, negotiating and managing the evolving community of “everyone that matters” and their needs – much of the minutiae of the Twelve Principles, and debates thereon, evaporates.

In a nutshell: we must attend not only to the needs in the context of the particular product or service under development, but also to the needs of everyone that matters in the context of the means (conduct, organisation) of that development effort.

– Bob